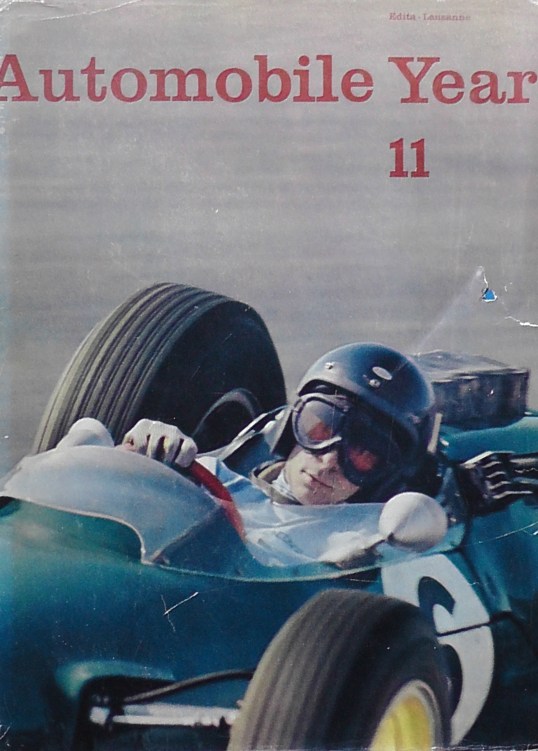

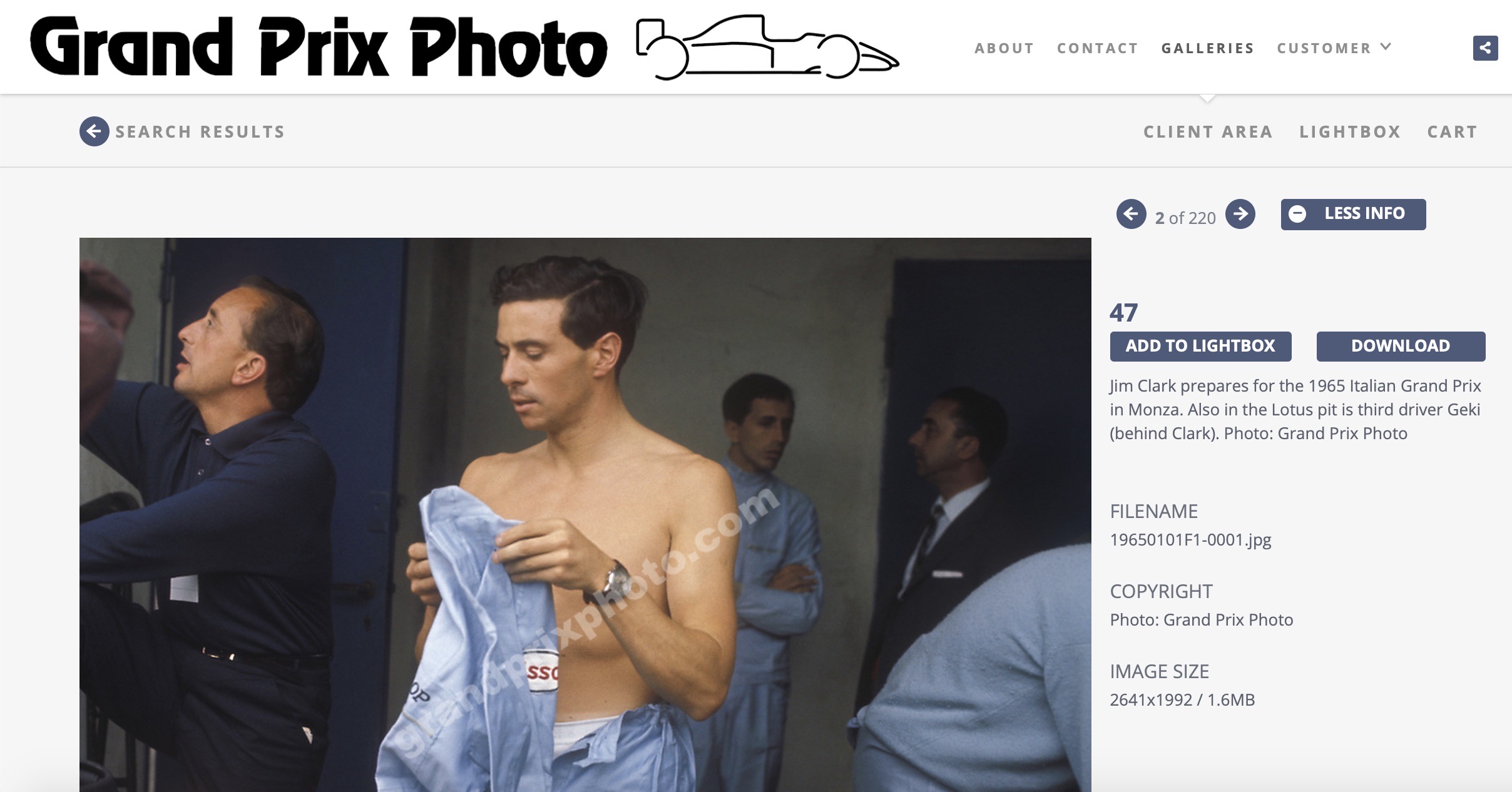

“Jim Clark, rhythmically poised…”

Perfectly balancing smaller diameter rear Dunlops on an oily Silverstone track surface, Jim Clark wins the British GP

After a whirlwind start to the year Jim Clark was able to relax for a few days. Three successive wins enabled him to enjoy the farm like never before; and, back in Balfour Place for a few days before the run up to Silverstone, Sir John Whitmore was full of Rob Slotemaker’s antics and all the recent racing news. In between, however, there was the little matter of the Milwaukee test. The Indy Lotus 29-Fords had basically been garaged at the Speedway since the race but, in the build-up to the Milwaukee 200 on August 18, rebuilds and further fettling took place at Ford’s headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. Jim flew to Chicago on July 10 and on July 12 completed a successful day at the one-mile Milwaukee oval, running through Dunlop tyre compounds and in the process raising the average lap speed – over one mile! – by nearly 5mph.

After a whirlwind start to the year Jim Clark was able to relax for a few days. Three successive wins enabled him to enjoy the farm like never before; and, back in Balfour Place for a few days before the run up to Silverstone, Sir John Whitmore was full of Rob Slotemaker’s antics and all the recent racing news. In between, however, there was the little matter of the Milwaukee test. The Indy Lotus 29-Fords had basically been garaged at the Speedway since the race but, in the build-up to the Milwaukee 200 on August 18, rebuilds and further fettling took place at Ford’s headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. Jim flew to Chicago on July 10 and on July 12 completed a successful day at the one-mile Milwaukee oval, running through Dunlop tyre compounds and in the process raising the average lap speed – over one mile! – by nearly 5mph.

Dan Gurney, who also tested at Milwaukee, had meanwhile shared a Ford Galaxie with Jack Brabham in the Six-Hour Race at Brands Hatch on July 7. A massive spin at Paddock in the rain (due to having to run Firestone wets on the front and Goodyear dries on the back) had cramped his style somewhat. Mike Parkes had cleaned up at Silverstone in his GTO Ferrari but, worryingly, the day had been ruined by two fatal accidents – one (John Dunn) at Abbey in the Formula Junior race and another in the pit lane (Mark Fielden, whose stationary Lotus was hit by a car spinning its way out of Woodcote). The excellent Sheridan Thynne, who would later become Commerical Director of Williams F1, won his class and set fastest lap at Snetterton in a Mini and a few days later wrote poignantly to Autosport, suggesting that a Safety Committee be convened to look into all matters of motor racing safety “before they were underlined by fatal accidents”. Sadly, as ever, his words went unheeded: a third person (a pit lane scrutineer, Harald Cree) would be killed at Silverstone on British GP race day when the very talented Christabel Carlisle spun her Sprite into the Woodcote pit wall. In another Woodcote incident, former driver and future Goldhawk Road car dealer, Cliff Davis,  would exhibit immense bravery as he leapt onto the track to clear it of debris after an MGB rolled itself to destruction. Davis was later deemed to have saved several lives. Lorenzo Bandini, who would finish an excellent fifth at Silverstone in his the old, red, Centro Sud BRM, had not only won for Ferrari in the big sports car race at Clermont-Ferrand but had also been a part of the first all-Italian win at Le Mans on June 15-16. He co-drove a Ferrari 250P with Ludovico Scarfiotti; and, in the Formula Junior race at Clermont, Jo Schlesser had won from an amazing line-up of future stars – Mike Spence, Peter Arundell, Tim Mayer, Richard Attwood, David Hobbs, Alan Rees and Peter Revson. John Whitmore himself had won the Mini race at Silverstone after a big dice with Paddy Hopkirk – and Tim Mayer, that FJ star and future McLaren driver – had even raced a Mini at Mallory Park, door-to-door with Paddy Hopkirk. Whilst up in Scotland, Jim had been able to catch up with young Jackie Stewart, who had won at Charterhall in the Ecurie Ecosse Tojeiro on the same day as the French GP; and, finally, with the London premiere of Cleopatra set for July 31, Jim had thought it a good moment to ask Sally Stokes if she might be free for a night on the town…

would exhibit immense bravery as he leapt onto the track to clear it of debris after an MGB rolled itself to destruction. Davis was later deemed to have saved several lives. Lorenzo Bandini, who would finish an excellent fifth at Silverstone in his the old, red, Centro Sud BRM, had not only won for Ferrari in the big sports car race at Clermont-Ferrand but had also been a part of the first all-Italian win at Le Mans on June 15-16. He co-drove a Ferrari 250P with Ludovico Scarfiotti; and, in the Formula Junior race at Clermont, Jo Schlesser had won from an amazing line-up of future stars – Mike Spence, Peter Arundell, Tim Mayer, Richard Attwood, David Hobbs, Alan Rees and Peter Revson. John Whitmore himself had won the Mini race at Silverstone after a big dice with Paddy Hopkirk – and Tim Mayer, that FJ star and future McLaren driver – had even raced a Mini at Mallory Park, door-to-door with Paddy Hopkirk. Whilst up in Scotland, Jim had been able to catch up with young Jackie Stewart, who had won at Charterhall in the Ecurie Ecosse Tojeiro on the same day as the French GP; and, finally, with the London premiere of Cleopatra set for July 31, Jim had thought it a good moment to ask Sally Stokes if she might be free for a night on the town…

The British Grand Prix was held on Saturday, July 20, (oh for a return to Saturday racing!) which meant that the big event of the weekend would undoubtedly be Graham Hill’s party at his Mill Hill house on the Sunday. Prior to that, there was a little bit of business to which to attend. Most of the F1 teams began testing on Tuesday, prior to practice on Thursday and Friday morning, and Jim was almost immediately on the pace. I say “immediately”: a loose oil line lost him time on Thursday morning but he was quickest by a whole second from Graham Hill (spaceframe BRM) later that day and fractionally faster than his Indy team-mate, Dan Gurney (Brabham), on Friday. Jim thus took the pole with a 1min 34.4sec lap of Silverstone, equaling Innes Ireland’s very fast practice times with the BRP Lotus 24-BRM at the International Trophy meeting on May 11. (Years later, when I chatted to Jim Clark at some length, he re-iterated what he frequently said about the space-frame Lotus 24: it was an easier car to drive than the 25 and in Jim’s view could just have capably have won races in both 1962 and 1963. Indeed, Innes’ Goodwood-winning Lotus 24 was actually being advertised for sale by the time of the British GP, viewable at BRP’s headquarters in Duke’s Head Yard, Highgate High Street, London N6. It wasn’t sold that year, as it turned out, and was raced again, in Austria and Oulton Park, by Innes. Jim Hall then drove it – for BRP – at Watkins Glen and Mexico.)

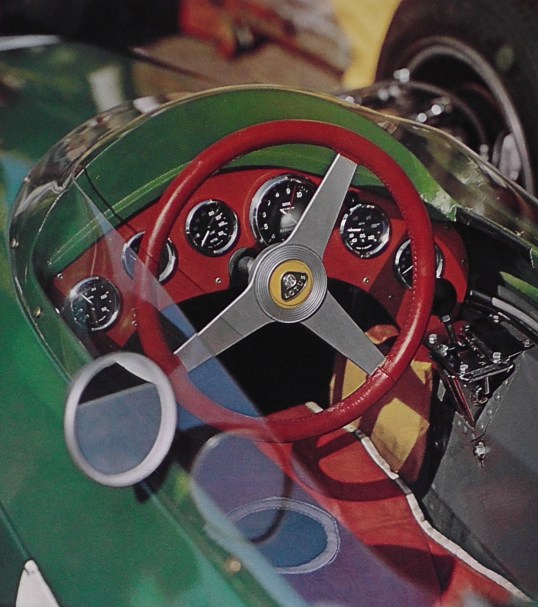

Still running a five-speed ZF gearbox (whilst team-mate Trevor Taylor persisted with the six-speed Colotti on carburettors), Jim’s trusty, fuel-injected Lotus 25/R4 had now blossomed into its ultimate, legendary 1963 form: Colin Chapman had decided to run a wide yellow stripe down the car, front to rear, co-ordinating the yellow with the wheels and the “Team Lotus” lettering and pin-striping down the cockpit sides. The car also ran the Zandvoort-spec aeroscreen. Jim, as ever, wore his Dunlop blue overalls, his peakless Bell helmet, string-backed gloves, Westover boots and, for when he was out of the car, helping the mechanics or strolling over to the Esso caravan or the paddock cafe for a cuppa, his dark blue Indy Pure jacket. The 25, meanwhile, finally wore a new set of Dunlops – around which revolved the usual number of discussion points. On this occasion it was gear ratios: as part of the compromise with the five-speed (but more reliable) gearbox, Jim and Colin decided to race smaller-diameter rear Dunlops.

Bruce McLaren, driving the beautiful, low-line works Cooper-Climax, stopped practice early on Friday to begin preparation for the race.  While John Cooper supervised the job list, Bruce, as was his style, took his new E-Type Jag down the infield runway to the apex of Club Corner, there to watch his peers. At this point I can do no better than to record the words he later gave to Eoin Young for Bruce’s wonderful, regular, Autosport column, From the Cockpit:

While John Cooper supervised the job list, Bruce, as was his style, took his new E-Type Jag down the infield runway to the apex of Club Corner, there to watch his peers. At this point I can do no better than to record the words he later gave to Eoin Young for Bruce’s wonderful, regular, Autosport column, From the Cockpit:

“Dan Gurney had got down to a time equaling Jim’s best, and Jim was out to see if he could do better. Graham was in danger of being knocked off the front row so he was out too, and for 15 minutes, while Jim, Graham and Dan pounded round, I was graphically reminded of the reason why people go to see motor racing.

“When you’re out in an F1 car you haven’t got time to think about the fact that you’re moving fast: you’re concentrating on keeping the movement of the car as smooth and as graceful as possible, getting the throttle opened just that fraction quicker than last time and keeping it open all the way when you’ve got it there.

“At Silverstone you concentrate on shaving the brick walls on the inside, just an inch or two away, and you hold the car in a drift that, if it were any faster, would take you into a bank or onto the grass. If you are any slower you know you are not going to be up with those first three or four. You know perfectly well you are trying just as hard as you possibly can, and I know when I’ve done a few laps like this I come in and think to myself, well, if anyone tries harder than that, good luck to them.

“But you haven’t thought about the people who are watching. At least I haven’t, anyway, but there at Club Corner the role was reversed and I was watching…

“Jim came in so fast and left his braking so late that I leapt back four feet, convinced that he wouldn’t make the corner, but when he went through, working and concentrating hard, I’m sure his front wheel just rubbed the wall. I barely dared to watch him come out the other end.

“It struck me that Clark and Gurney’s experience at Indy this year may have had something to do with their first and second places on the grid. Silverstone is just one fast corner after another, taken with all the power turned right on and the whole car in a pretty fair slide but, nevertheless, in the groove for that corner. Something like Indy, I should imagine.

“I’ve seen a lot of motor racing and if I could get excited over this I can imagine how the crowd of 115,000 on Saturday must have felt.”

Saturday was one of those great sporting occasions in the United Kingdom. One hundred and fifteen thousand people were crammed into Silverstone by 10:00am; and by 2:00pm, by which time they’d seen Jose Canga two-wheeling a Simca up and down pit straight; Peter Arundell win the FJ race from “Sally’s MRP pair” (Richard Attwood and David Hobbs); Graham Hill demonstrating the Rover-BRM turbine Le Mans car; an aerobatic display and the traditional drivers’ briefing, everyone was ready for the big event. Dan Gurney settled into his Brabham with Jim Clark to his right in the Lotus 25. To Dan’s left, Graham Hill, the World Champion, lowered his goggles under the pit lane gaze of young Damon. Making it four-up at the front, Dan’s team-mate, Jack Brabham, sat calmly in his BT7. With but minutes to go, Jim asked for more rear tyre pressure: Silverstone had felt decidedly oily on the formation lap. The 25 had never been more oversteery.

Jim was slow away on this occasion: wheelspin bogged him down. He was swarmed by the lead pack as they headed out of Copse and then onwards to Maggotts and Becketts. The two Brabham drivers – showing how relatively closely-matched the top Climax teams were in 1963 – ran one-two; then came Bruce McLaren in the svelte Cooper, then Hill and then Jim. They were running nose-to-tail – and sometimes closer than that. Gurney pitched the Brabham into oversteer at Club; Jack, helmet leaning forwards, kicked up dirt at the exit of Woodcote.

Jim was slow away on this occasion: wheelspin bogged him down. He was swarmed by the lead pack as they headed out of Copse and then onwards to Maggotts and Becketts. The two Brabham drivers – showing how relatively closely-matched the top Climax teams were in 1963 – ran one-two; then came Bruce McLaren in the svelte Cooper, then Hill and then Jim. They were running nose-to-tail – and sometimes closer than that. Gurney pitched the Brabham into oversteer at Club; Jack, helmet leaning forwards, kicked up dirt at the exit of Woodcote.

The 25 was also tail-happy; you could say that. Jim felt the car to be little better than it had been before the start – particularly now, on full tanks. Around him, though, everyone else seemed to sliding around. Maybe it was just the circuit after all…

Jim began to dive deeper into the corners, to gain a tow – and then to pull out of that tow under braking. By lap four he was in the lead and pulling away…whilst Bruce McLaren was pulling up on the entry to Becketts Corner, the Climax engine blown in his Cooper. There was no quick rush back to the pits for Bruce, no beat-the-traffic early departure. Instead, as on Friday, he stayed and watched, for that is what great athletes do.

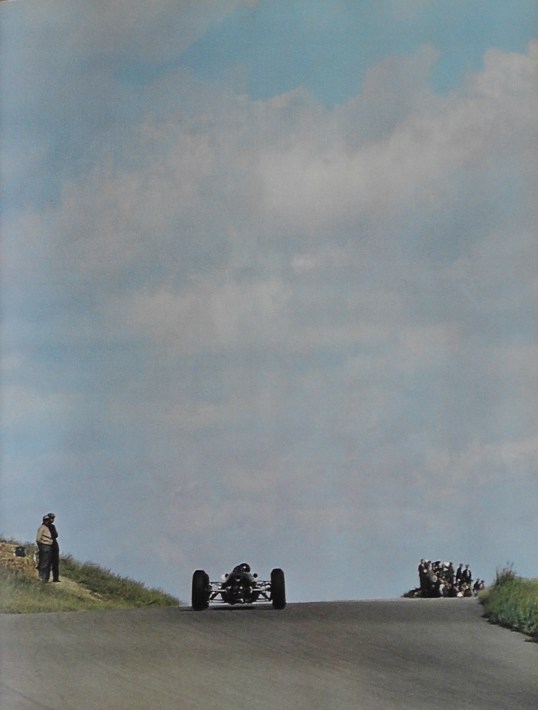

Bruce: “Jimmy came through with his mouth open and occasionally his tongue between his teeth. The tyres were holding a tenuous grip on the road with the body and chassis leaning and pulling at the suspension like a lizard trying to avoid being prized off a rock by a small boy. Then Dan arrived, really throwing the Brabham into the corner, understeering and flicking the car hard until he had it almost sideways, then sliding through with the rear wheels spinning and the inside front wheel just on the ground…” It was a demonstration of four-wheel-drifts; it was Jim Clark rhythmically poised like never before in an F1 car, the small-diameter Dunlops combining with the surface oil to produce a slide-fest of classic proportions. There was no need for a score of passing manoeuvres to make this British GP “work” for the crowds; there was no need for forced pit stops or for overtaking aids. It was enough, this day at Silverstone, for the fans, and for drivers of the quality of Bruce McLaren, merely to see a genius at work.

It was a demonstration of four-wheel-drifts; it was Jim Clark rhythmically poised like never before in an F1 car, the small-diameter Dunlops combining with the surface oil to produce a slide-fest of classic proportions. There was no need for a score of passing manoeuvres to make this British GP “work” for the crowds; there was no need for forced pit stops or for overtaking aids. It was enough, this day at Silverstone, for the fans, and for drivers of the quality of Bruce McLaren, merely to see a genius at work.

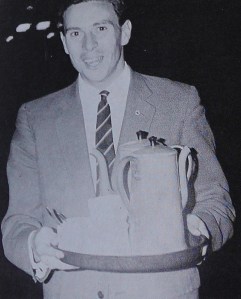

Jim won the British Grand Prix by 20sec from John Surtees’ Ferrari and Graham Hill’s BRM (for both Brabham drivers also lost their engines after excellent runs). Graham, who, like Innes Ireland, was always fast at Silverstone, ran short of fuel on the final lap and was pipped by Big John, the lone Ferrari driver, on the exit from Woodcote. The race was also notable for Mike Hailwood’s F1 debut – he finished an excellent eighth (or, in today’s parlance, “in the points”) with his Parnell Lotus 24, and for the seventh place of his exhausted team-mate, the 19-year-old Chris Amon. Chaparral creator/driver, Jim Hall, also drove well to finish sixth with his Lotus 24. For this was a tough, hard race – 50 miles longer than the 2013 version and two and a quarter hours in duration. Jim Clark waved to the ecstatic crowd on his slow-down lap (no raised digits from James Clark Jnr) and, to the sound of Scotland the Brave – a nice touch by the BRDC – and to the lucid commentary of Anthony Marsh, bashfully accepted the trophies on a mobile podium that also carried the 25. Colin Chapman wore a v-necked pullover and tie; Jim looked exalted. He had won again at home. He had won his fourth race in a row. He had the championship in sight.

Jim won the British Grand Prix by 20sec from John Surtees’ Ferrari and Graham Hill’s BRM (for both Brabham drivers also lost their engines after excellent runs). Graham, who, like Innes Ireland, was always fast at Silverstone, ran short of fuel on the final lap and was pipped by Big John, the lone Ferrari driver, on the exit from Woodcote. The race was also notable for Mike Hailwood’s F1 debut – he finished an excellent eighth (or, in today’s parlance, “in the points”) with his Parnell Lotus 24, and for the seventh place of his exhausted team-mate, the 19-year-old Chris Amon. Chaparral creator/driver, Jim Hall, also drove well to finish sixth with his Lotus 24. For this was a tough, hard race – 50 miles longer than the 2013 version and two and a quarter hours in duration. Jim Clark waved to the ecstatic crowd on his slow-down lap (no raised digits from James Clark Jnr) and, to the sound of Scotland the Brave – a nice touch by the BRDC – and to the lucid commentary of Anthony Marsh, bashfully accepted the trophies on a mobile podium that also carried the 25. Colin Chapman wore a v-necked pullover and tie; Jim looked exalted. He had won again at home. He had won his fourth race in a row. He had the championship in sight.

To Mill Hill, then, they repaired – and then, for a change in pace, to the following weekend’s non-championship race at Solitude, near Stuttgart.

Captions, from top: Jim Clark drifts the Lotus 25 on the greasy Silverstone surface; racing driver/flag marshal, Cliff Davis, whose selfless action at Silverstone saved several lives; Bruce McLaren finds slight understeer on the Cooper at Stowe; the two Brabham drivers, Gurney and Jack, together with McLaren and Hill, crowd Jim’s 25 at the start; classic four-wheel-drift from Jim Clark. The low apex walls were always a test at 1960s Silverstone; Scotland the Brave heralds the winner of a long, fast British Grand Prix. Two hours, 14 min of brilliant motor racing Images: LAT Photographic. Our thanks to AP and Movietone News for the following superb, colour, video highlights: