You stand there amongst the trees, on the inside of the Parabolica, watching and listening – with emphasis on the music. Screaming revs, shrill and pure. Then a millisecond-pause. Then more revs as they play with the steering and brakes, “looking for the moment,” as Ayrton Senna used to say (when people asked him why he dabbed the throttle so) “when I can give it full power.”

You push your ear plugs in further; you peer again up to Ascari, where a morning haze is already giving way to a golden Italian sun.

It’s red! And the baby-blue helmet sits amidships. Fernando keeps the F2012 tucked neatly to the right, parallel to the white line, as the car bursts up through the speed range – through fifth, sixth and then into seventh. He sits at terminal for what seems like two seconds, maybe three – and then he moves the car sharply to the left, for the approach to the Parabolica. Where other drivers have seemed reflexy, wary of the dust off line (for Monza, sadly, is rarely used these days thanks to noise restrictions), Fernando is commandingly positive with his movements. He talks, the Ferrari listens. There’s no nonsense. He doesn’t wander across track on the approach to the Parabolica in a conventional diagonal. Everything is load-free and clean. His helmet sits perfectly at low-drag height. The Ferrari looks all-consumingly beautiful – functional and sharp – on this gorgeous day at Monza.

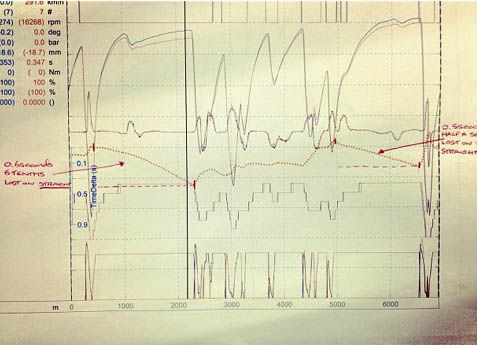

So when the problems arose – three of them, one after the other – engine, brakes, gearbox! What the…!” – the Ferrari world stood still. The F2012 has been up and down this year but never fragile. And now here, of all places, it seemed to be unravelling. No matter that the engine and gearbox were no longer a part of the race cycle and could be replaced without penalty. No matter that the Brembo boys quickly took charge of the brakes. Fernando could manage only 17 laps in the afternoon. At Monza. In practice for the Italian Grand Prix.

What gear ratios to choose? What downforce levels to run? Decisions needed to be made that Friday afternoon. The Ferrari felt quick, the balance good, the grip level high for a circuit so fast; Felipe, in the other, ultra-reliable car, confirmed the findings. And so they opted to maintain that little extra downforce when it became time to register gear ratios with the FIA. The pole – or the front row – were going to be critical. Front wings could be lost in that tight first corner. Fernando needed to aim for the best-possible lap, even if it did mean that he’d perhaps suffer on Sunday if he became embroiled in traffic. The pole – or the front row – was the thing. It was, despite the problems, very attainable. A shorter seventh was registered. Fresh engines crackled up and down the pit lane on Saturday morning, for Monza is a spike in the schedule that must be scrupulously observed, an engine circuit in the old tradition.

And the Ferrari was brilliantly quick. Down at Red Bull, where Sebastian Vettel and Mark Webber were complaining of having nothing like the same grip as 2012, the drivers were having to adopt to the compromise solution of longer gearing and less downforce. “Now,” said a rival engineer ruefully, “Red Bull are back in the real world…” At McLaren, where Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button were enjoying their runs in the gorgeous low-drag-spec MP4-27As, Ferrari’s pace nonetheless remained a talking-point, a pivotal strategy marker.

Qualifying would be razor-close – perhaps a defining moment. It would be Ferrari versus McLaren. It would be Fernando, regaining momentum. It would be Lewis or Jenson, McLaren-perfect.

Fernando felt the problem even as he drove his out-lap in Q3. The back felt strange, sloppy. A puncture? He zapped the car a few more times, searching for temperature. He gunned it down the pit straight. He braked perfectly for the first chicane. He came out of the Brembos nice and smoothly, fed in the steering – and the back jolted away from him. Gone! Q3 gone!

On the radio they could hear them talking about a puncture. He drove back in to the garage. He sat there. They talked and looked – and then came the news. “Fernando. We have a broken rear roll-bar mounting. There’s nothing we can do now. You’ll just have to go out and see if you can pick up a few grid places.”

Despite the problem, Fernando produced what to my eye was still a neat-looking lap. He was a little more squirrelly out of Ascari, a little more reticent out of Parabolica. 1min 25.768sec. He couldn’t pick up any places – he would start tenth – but he did drive the nuts off the thing, bringing to mind the performance of Jim Clark at Monaco in ’64, when his rear roll-bar mount broke, too – and still he led the race. Having said that, a number of rival team engineers were intrigued to see how just how much difference – 1.5 sec – the broken rear roll-bar actually made to the F2012. Read into that what you will.

Lewis and Jenson thus took the front row. Felipe was an excellent third, ahead of Sahara Force India’s Paul di Resta, Michael in the Mercedes, Seb Vettel, Nico and then Kimi in the Lotus-Renault. Then came Kamui Kobayashi’s Sauber and Mark Webber in the other Red Bull. For the second successive race, Sergio Perez was behind his team-mate. “I caught Bruno on my last Q2 run,” he said as I ran alongside him pre-race. “He didn’t impede me or anything but I lost downforce.” Interesting comment, that, bearing in mind that Bruno, too, said he lost downforce behind the Perez Sauber! The Saubers weren’t brilliantly quick in a straight line at Monza but they were looked fast on the quick corners – as did the Force Indias. There was lots of talk about “strong DRS” or “weak DRS” – and I guess we have to conclude that the Force India falls into the former catergory, given its relative superiority in qualifying. The conventional wisdom of the Monza paddock was that Mercedes- and Ferrari-engined cars additionally enjoyed a marked advantage. Examination of the post-qualifying speed trap showed the Lotus-Renaults right up there with the McLaren-Mercedes, possibly at the expense of some downforce, and so on this occasion I defer to the record of Renault at Monza: it is not at all bad….

Nothing, though, this Saturday at Monza, was a distraction from the calamity that was the broken rear anti-roll bar mounting on Fernando’s Ferrari. It was a black day for Maranello – and doubly-so because it was Monza. It was a manufacturing fault, a slight glitch that was magnified a millionfold in the chaos of the afternoon. Fernando was where he didn’t want to be: in the first-corner traffic at Monza’s Turn One.

Pre-race, Fernando’s thoughts about that corner were “open”. “I decided just to see how the start went,” he said later. “If I made a good start I would see where I was. If I didn’t it would be another story.”

Fernando didn’t make a good start; he made a great one. So did Felipe. Felipe squeezed past Jenson and darted left into the braking area, crowding Lewis. Fernando gained ground, found a bit of clear track ahead of him and so decided to “be aggressive”. You can’t half-race if you’re Fernando. You race. He came out of the corner side-by-side with Kobayashi. He did him at the next chicane.

Monza began to throb. McLaren or no McLaren, Fernando was in it. All was not lost. P4 perhaps – maybe P3, although many were the cars to be passed.

There was the usual drama with Michael. Be squeezed and then be squeezed again. And then, holding back a little into the Parabolica, feed in the power just as Michael is twitching it, mid-corner. Get a run on him. Move earlier than he expects. Put the car out there. Look straight ahead into the braking area. Brake late but brake perfectly, on the groove. Let Michael look for grip down the inside.

Kimi, in comparison, had been an easier target. Seb Vettel, though, was not going to give him anything – and Fernando expected as much. Last year Fernando had not made it easy for Seb when the Red Bull had caught him on the approach to the Curva Grande. Fernando hadn’t chopped him or moved on him; on the contrary, he had just driven through absolutely in the middle of the road, giving Seb the option to choose to run to the left or to the right.

Now, as Fernando sat behind Seb, moving a little to the left here or the right there, feeling him out, Seb’s body language said it all: this was going to be a drama.

Fernando waited and teased, waited and teased. And then, drawn inexorably towards the Curva Grande after Seb’s slowish exit from the chicane, Fernando also moved to the outside.

Seb moved left, stealing the road. Fernando, on the grass, fought with the steering even as he lifted only a fraction. Monza momentarily ceased to breathe.

Fernando backed away and calmly pressed his radio button: “OK. That’s enough….”

He waited and teased, waited and teased, wondering now if he had damaged the underside at all. The car felt slightly less grippy on the slow corners, slightly less stable under braking; he needed to be super-precise with everything he did.

Then there came a more open door: Seb, now “under investigation”, slowed markedly. Fernando made the pass. For easing Fernando off the road, Seb earned a drive-through.

Felipe would slow to let Fernando pass; that was never in doubt – and Fernando was quicker, anyway, in the later stage of the race, when they were both on hard tyres. Jenson lost a sure second place with a fuel pick-up problem. Fernando would after all finish as high as P2.

Or would he? Monza had not yet released its grip on Fernando’s weekend. Sergio Perez’s traffic issue in Q2 had allowed him to start on Pirelli primes. He drove beautifully in his first stint, running longer even than the meticulously-driven McLarens, and thus alone amongst the high-end of the field – in this one-stop race – faced the closing laps on relatively fresh Pirelli options. He maximised them. He pumped out lap after brilliant lap, free road or otherwise. He caught Felipe and passed him into the Parabolica, where he was perhaps five or six mph faster on entry. To the dismay of Monza he did likewise to Fernando. There was nothing to do; Pirelli options, at that stage of the race, were a huge bonus, the more so because the fastest way to race Monza was with only one stop for tyres. To put Sergio’s pace into perspective, though, imagine a race in which all of the Q3 runners had been able to start on primes and then switch to options. That is what Kamui Kobayshi should be telling himself as he comes to terms with the differences between his own race and Sergio’s – although, in telling the Japanese media that he “did all that could have been expected of him at Monza”, he should perhaps also reflect on why Perez was able to pass him as early as lap seven, when he, Kamui, was on options and Sergio, of course, was on primes. I guess one has to factor in Kamui’s lack of running on Friday (when for some unexplained reason he found the car undriveable even on the straights). Mark Webber, too, must be wondering why he started from P11 on options (although, having said that, he ran out of rear primes towards the end of the race: again, this puts Sauber’s performance into sparkling perspective).

Lewis from the start of the year has always been the driver most likely to race Fernando hardest to the 2012 World Championship – and so it proved at Monza, where he bit a ten-point chunk from Fernando’s lead. It could have been more, though; much more. Fernando after all faced the podium crowd, TV camera aloft, with his day safe and secure. Despite the problems on Friday or the roll-bar on Saturday. Despite the gear ratios, despite the Vettel pass. And Monza itself could rest again. It’s quiet now, down at the Parabolica, down amongst the trees and the fallen leaves. The track is empty, the litter swept away. The red car, though, the blue helmet angled back slightly, still lingers, vivid in the memory.

Left: Fernando films his moment

Left: Fernando films his moment

Below: “Yes, Ma, I finished second…”