From Trenton back to London; from London to New York and then on to Elmira, the small airport local to Watkins Glen. The 1963 US GP would be Jim Clark’s first as World Champion.

From Trenton back to London; from London to New York and then on to Elmira, the small airport local to Watkins Glen. The 1963 US GP would be Jim Clark’s first as World Champion.

Jim loved his days at The Glen; everyone did. The leaves had by now turned red and brown; there was a mist in the mornings that lifted only as the sun broke through before noon. And this was a Grand Prix run by good, racing people – men like Cameron Argetsinger, who had brought motor racing to Watkins Glen in 1948, Media Director, Mal Currie, and Chief Steward, Bill Milliken. All had rich racing and automotive histories. Milliken had been a Boeing test engineer during World War II and had joined the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory (Calspan) in 1945. As an avid Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) member and former driver/designer, Bill in 1960s and 1970s became the doyen of US automobile engineering research. He was, in short, the sort of Chief Steward in whose presence you doffed your cap. The drivers and key team people stayed nearby at the Glen Motor Inn, hard by the Seneca Lakes, where their hosts were Jo and Helen Franzese, the second-generation Italian couple who loved their F1. Legends were born overnight at the Glen Motor Inn – and even at the old Jefferson hotel downtown. Lips, though, were always sealed. Such was life that October week at The Glen.

Ford made a big splash, too, this year of the Lotus-Ford at Indy. This was the US GP! Sixty thousand fans were expected. Cedric Selzer, hooking up with the Team Lotus “US guys” for this race, remembers the drive up from New York airport on the Tuesday before the race: “We were given the keys of a saloon, a coupe and a convertible and made our way out of the city, heading for Watkins Glen. When we stopped at traffic lights, people came over and asked us about the cars. We told them we’d got them from the Ford Motor Company but it took us three days to realize that we’d all been given 1964 models than no-one had seen before.

“The following afternoon, Jim Endruweit hired a Cessna 180, with a pilot, and we flew over the Finger Lakes. It was autumn, and the seasonal colours were unbelievable.It seemed a shame when it was time to get back to the task of winning a motor race…”

Milliken remembers the pre-race party: “High point of the festivities were the parties at the Argetsinger’s home in Burdette. All drivers and officials were there in an atmosphere or pure fun and excitement, bolstered by great conversation, good food and dozens of magnums of champagne from the local vineyards. The homespun hospitality led to permanent friendships and was never forgotten by the drivers or teams.”

Practice took place over eight absorbing hours, split between two four-hour sessions on Friday (1pm-5pm) and again on Saturday (11am-3pm). There was a bit of a fracas when, first, Peter Broeker’s Canadian-built four-cylinder Stebro-Ford began spewing – and continued to spew – oil around the circuit, and, second, when Lorenzo Bandini slowed down after a blind brow to talk to his sidelined Ferrari team-mate, John Surtees. Richie Ginther and Jack Brabham narrowly missed the Number Two Ferrari, igniting a bit of finger-pointing back in the pits and plenty of “I no-a speak-a di Eengleesh…”.

The Glen in 1963 featured the brand new Tech Centre on top of the hill behind the pits (which were then sited after today’s Turn One), allowing all the teams (except Ferrari, who continued to use Nick Fraboni’s Glen Chevrolet garage and therefore to truck their cars up from the town each morning), to work on their cars in situ, in communal spirit and to be energized by plenty of lighting and electric sockets. (The F1 teams were obliged to convert to the American standard 110volts. On the face of it, this didn’t seem to be a problem. As it turned out, it was.) For a small incremental fee, race fans could also walk up and down the Kendall shed, looking at the cars at close hand. GP2 could learn a thing or two from The Glen, 1963…

Jim, in relaxed mood, qualified second, 0.1 sec behind Graham Hill’s old space-frame BRM. Milliken also recalls in his excellent autobiography (Equations in Motion, with an introduction by Dan Gurney) that the timekeepers “always had problems with Colin Chapman. Colin timed his own entries and claimed his faster figures were correct, so Bill Close, one of our timers and a solid Scotsman, put two clocks on each Lotus…”

Trevor Taylor, whose car caught fire in the paddock on Saturday, qualified seventh; and Pedro Rodriguez, having his first F1 drive, and fresh from a win for Ferrari in the Canadian GP sports car event, was 13th in the carburettor-engined 25. This wasn’t a happy weekend for Trevor: Chapman chose the US GP to tell him that he wouldn’t be retained for 1964. His place would be taken by Lotus’ FJ king, Peter Arundell.

Bruce McLaren lost most of the Saturday morning session when his Cooper-Climax lost oil pressure; and so – as at the British GP – he used his time to watch, learn and compare. This from his notes in Autosport the following week: “Graham Hill finished his braking relatively early and had the power on, and the BRM a bit sideways, well before the apex of the slow corner at which I was watching. Jim Clark, on the other hand, braked hard right into the apex with the inside front wheel just on the point of locking as he started to turn.”

Jim’s race was defined on the dummy grid. Due to what was later found to be a faulty fuel pump, his 25 wouldn’t start. And then, very quickly, the battery went flat. Selzer: “The truth is that the battery had not taken a proper charge overnight. We used a dry-cell aircraft battery made by Varley with six, white-capped cells. Somehow, we never got the hang of keeping them fully-charged. America was a special case as we had to borrow a 110 volt charger. We used a ‘fast’ charger when actually what was required was a ‘trickle’ charger. As Jim was left way behind the grid proper, two of us ran over to him and changed the battery. This meant that Jim had to climb out whilst we removed the tail and nose sections of the car in order to get at the battery, which was under the seat.”

I recently bought an audio CD of the 1963 US GP and Stirling Moss provides an hilarious description of these moves whilst watching the start from the main control tower.

“I can see lots of people gathered around Jim Clark’s car. Looks as though they’re trying to remove the bonnet…no…what is it that you Americans call it? The hood? Yes, that’s right. The hood. They’re removing the hood. Meanwhile, I can see Graham Hill getting ready for the off….”

Jim eventually lit up the rear Dunlops just as the last-placed car completed its first flying lap. He would finish a brilliant third behind the two BRMs of Hill and Ginther (after Surtees’ V6 Ferrari broke a piston in the closing stages) – but it could have been even closer. “That mishap on the grid was what I needed to put me back into a fighting mood,” remembers Clark in Jim Clark at the Wheel, “and so I set off after the field, knowing I was going to enjoy the race. I began to catch up the field, and to thread my way through, until I saw Graham Hill in front of me. I thought I was at least going to have a dice with my old rival, albeit with me being a whole lap behind him. This was not to be, for shortly afterwards the fuel pump started acting up and it became a struggle even to keep him in view. I ploughed on through the race, during which many cars dropped out, and finally finished third.” Jim didn’t know it at the time but Graham, too, had been in major trouble: a rear roll-bar mount had broken on the BRM. Even so, it is typical of Clark’s character that he should sum-up his US GP with the phrase “…and finally finished third.” He was given to understatement; his mechanical sympathy in reality did the talking.

Neither of the other Lotus 25s finished, although Pedro showed the promise of things to come by slicing his way up to sixth before retiring with a major engine failure. Given the financial support the Rodriguez family were giving Team Lotus for The Glen and then the Mexican GP, the mechanics had to work very hard to rebuild that engine within the next few days. A new timing chain and valves were found after long “phone-arounds” and other broken valves were repaired at a local machine shop. David Lazenby, the lead “American” Team Lotus mechanic, returned to Detroit to begin installation of the four-cam Ford engine in the Lotus 29 – and he would be joined, once the Rodriguez engine rebuild was finished, by the F1 boys. Chapman was always one for keeping his lads amused…

Neither of the other Lotus 25s finished, although Pedro showed the promise of things to come by slicing his way up to sixth before retiring with a major engine failure. Given the financial support the Rodriguez family were giving Team Lotus for The Glen and then the Mexican GP, the mechanics had to work very hard to rebuild that engine within the next few days. A new timing chain and valves were found after long “phone-arounds” and other broken valves were repaired at a local machine shop. David Lazenby, the lead “American” Team Lotus mechanic, returned to Detroit to begin installation of the four-cam Ford engine in the Lotus 29 – and he would be joined, once the Rodriguez engine rebuild was finished, by the F1 boys. Chapman was always one for keeping his lads amused…

There was no podium at The Glen. As in other races back in 1963, it was the winner alone who took the plaudits and the laurel wreath (and, in the case of the US GP, the kisses from the Race Queen.) The new World Champion, after yet another astonishing race, would have quietly donned his dark blue, turtle-necked sweater, had a soft drink or two, helped the boys in the garage and then repaired to the Glen Motor Inn for a bath and a good dinner. The Mexican GP was three weeks away. On the Monday, Jim would journey back to New York and then fly across the continent to Los Angeles. Ahead, over the next two weekends, lay two sports car events for Frank and Phil Arciero, the wealthy (construction/wine-growing) enthusiasts from Montebello, California, who had already won many races with Dan Gurney. The first would be the LA Times Grand Prix at Riverside, where Jim’s “team-mate” would be his Indy sparring partner, Parnelli Jones. Then, the following weekend, he would race in the Pacific Grand Prix at Laguna Seca. On both occasions he would drive the Arciero’s new 2.7 Climax-engined Lotus 19….assuming it was ready. On the radio in his room that night at The Glen, with the still, cool air from the Lakes reminding him that the European winter was but a step away, Jim might have heard the Beach Boys chasing their Surfer Girl, or Peter, Paul and Mary Blowin’ In The Wind.

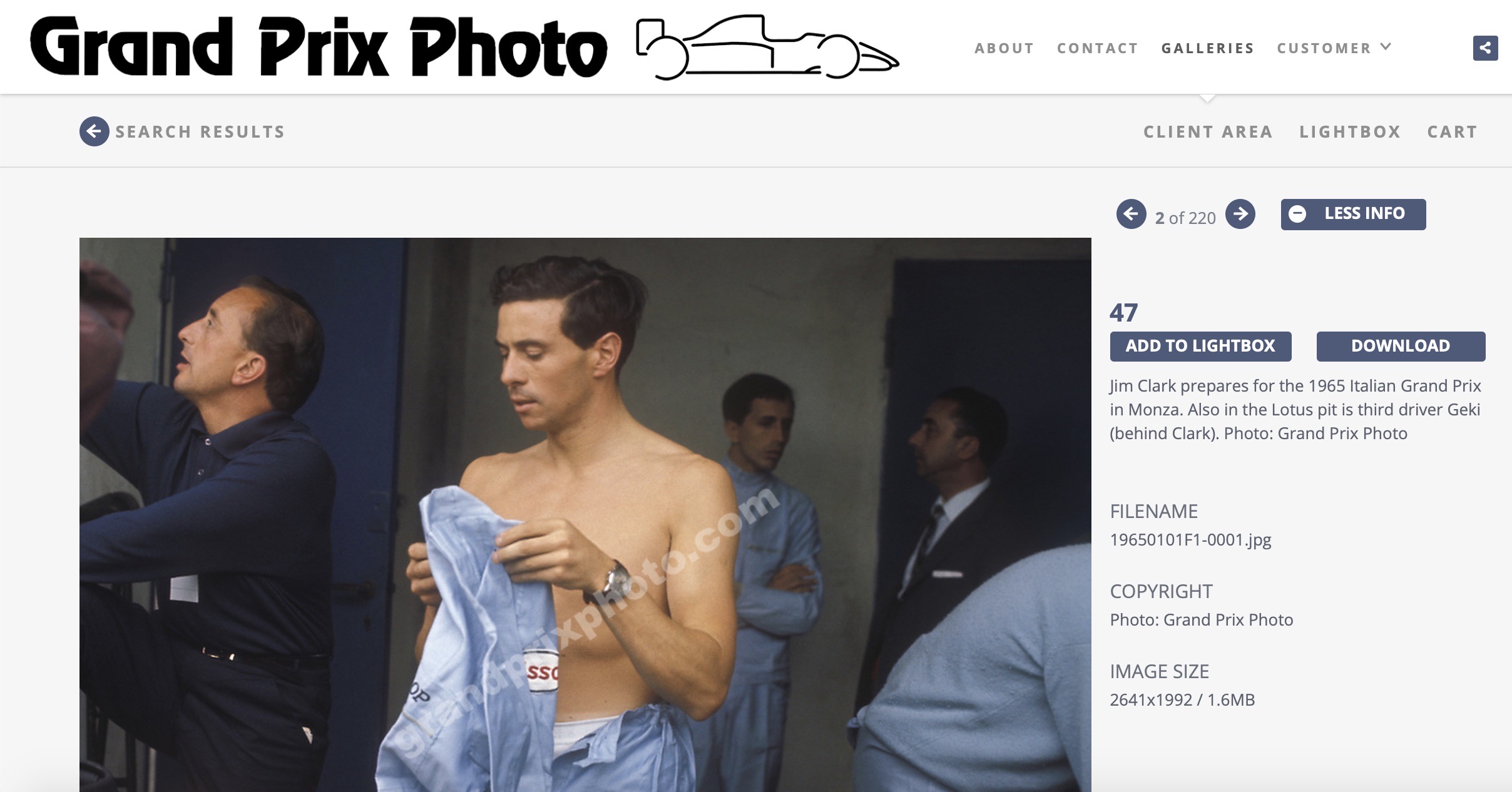

Captions, from top: Jim drifts the Lotus 25-Climax up through the Watkins Glen esses on his way to a fighting third place; less than a year after the loss of his brother, Ricardo, Pedro Rodriguez made his F1 debut at the Glen in a third works Lotus 25-Climax; classic pose: Jim displays the 25’s reclined driving position as he accelerates past an ABC TV tower Images: LAT Photographic

Buy Cedric Selzer’s wonderful new autobiography, published in aid of Marie Curie Cancer Care

Posted in

F1,

Jim Clark's 1963 season and tagged

Bill Milliken,

Cedric Selzer,

Colin Chapman,

Ferrari,

Glen Motor Inn,

Graham Hill,

Jim Clark,

John Surtees,

Lorenzo Bandini,

Pedro Rodriguez,

Team Lotus,

Trevor Taylor,

US GP,

Watkins Glen

It’s always a pleasure to watch the uphill Esses section at Suzuka during qualifying – particularly during qualifying because race conditions frequently restrict a driver’s pace and movement to the car he is following. In qualifying, though, when usually the air is free, it is different. And, for the most part, they’re all trying pretty hard.

It’s always a pleasure to watch the uphill Esses section at Suzuka during qualifying – particularly during qualifying because race conditions frequently restrict a driver’s pace and movement to the car he is following. In qualifying, though, when usually the air is free, it is different. And, for the most part, they’re all trying pretty hard.