Warwick Farm, the Tasman Series…and the cream of the world’s F1 drivers. It all came together in a golden age of Australian motor racing. Too quickly, though, it was over. The Farm was for the most part replaced by a housing estate; the Tasman became a championship too far. Geoff Sykes – dapper, under-stated, respected by all – rode into a motor-cycle- and aviation-oriented retirement.

Warwick Farm, the Tasman Series…and the cream of the world’s F1 drivers. It all came together in a golden age of Australian motor racing. Too quickly, though, it was over. The Farm was for the most part replaced by a housing estate; the Tasman became a championship too far. Geoff Sykes – dapper, under-stated, respected by all – rode into a motor-cycle- and aviation-oriented retirement.

Recently I was asked by the Australian Dictionary of Biography to write a brief profile of Geoff Sykes. This was my attempt to do him justice:

Geoffrey Percy Frederick Sykes was born on September 6, 1908, at Beresford Manor Cottage, Plumpton, Sussex, England. Percy Robert Sykes, Geoff’s father, was both a gifted wood-worker and the first Headmaster of the Chailey Heritage school for the disabled in Sussex, assisting disadvantaged children to forge their place in society. The eldest of three children (his sister, Marjorie, was born in 1910, his brother, Reginald, in 1913), Sykes was educated at Brighton, Hove and Sussex Grammar School, to which he travelled each day by moped and then by train, thus ensuring that he was licensed to ride a moped from the age of 12. Upon leaving school, he was apprenticed to British Thomas-Houston in Mill Road, Rugby – an electrical engineering industry leader. Certified as an electrical engineer in August, 1929, he then joined the Department of Works, where he was seconded to a number of public buildings, including Buckingham Palace.

Sykes married Margaret Rose White (a friend of his sister’s) on September 1, 1939. They had three children – Robert (born April 28, 1943), who worked for the British Council abroad and is now retired; Richard (born May 25 1945), who would study engineering and work for Ricardo, Tickford (where he was involved in the engine design of the Ford XR6) and TWR before joining Cosworth and subsequently Mahle Powertrain; and Julia (born August 15, 1948), who attended the Arts Educational School in London and taught dance for much of her career. She was subsequently appointed Secretary of two branches of the Imperial Society for the Teachers of Dancing.

Motor racing very quickly became a passion for Sykes. He regularly attended pre-war race meetings at Brooklands; he loved riding motor-cycles; and he competed in hill-climbs and trials with his open-topped Wolseley Hornet two-seater. Sykes was an active member of his local motoring club, the Brighton and Hove Motor Club (BHMC), and during this period also met John Morgan, who was then Secretary of the Junior Car Club.

At the outbreak of war, Sykes applied for a transfer first to the Air Force and then to the Army (which he would have joined at the rank of Major) but The Air Ministry instead commissioned Sykes to top-secret electrical engineering work, concentrating on the guiding of damaged aeroplanes to bases throughout England using the Drem lighting system. On one occasion, in the early dawn after the Luftwaffe’s bombing of Coventry, the aeroplane in which Sykes was flying was mistaken for the enemy. Despite considerable shelling, Sykes and crew survived unharmed.

Sykes worked in various management positions in the immediate post-war period before joining the Electrical Drawing Office at the Ministry of Works. Simultaneously he fostered his love of cars and motor-cycles with the Junior Car Club. The JCC amalgamated with the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club in 1949 (under a new name – the British Automobile Racing Club, or BARC), thus enabling Sykes, who by now had been elected Chairman of the BHMC, to work for the man who would become his mentor – John Morgan. A brilliant organizer and promoter, Morgan quickly established his reputation in British motor racing circles – and from 1954 did so with Sykes by his side. As the club’s Assistant General Secretary, Sykes, charming and mild-mannered, was an obvious counterpoint to the no-nonsense Morgan, the club’s General Secretary; and, as motor racing burgeoned in the 1950s, it did so in concert with the BARC’s growing stature. (It should also be noted that Sykes’ second wife, Meris Chilcott Rudder, also worked for the BARC at this time, married to the aviator, Jim Broadbent.)

His life changed dramatically when Mrs Mirabel Topham, owner of the Aintree horse-racing circuit in Liverpool, contacted the BARC in 1953 to discuss the design and construction of a motor racing circuit. After a number of meetings to discuss the project, she wrote to Morgan to say that she wished to go ahead but insisted that Geoff be the one she dealt with on a day-to-day basis. Under Sykes’ direction, the Aintree circuit was completed in 1954 and would go on successfully to stage the British Grand Prix on five occasions – 1955, 1957, 1959, 1961 and 1962. At many of these meetings – and at the early Grands Prix – Sykes officiated as Clerk of the Course.

In 1959 Sykes received a lawyer’s invitation to attend a meeting with the Australian Jockey Club (AJC) to discuss the design of an Australian version of Aintree. Unbeknown to Sykes, Sam Horden of the AJC had mentioned his motor racing circuit concept to the pre-eminent British Formula One private entrant, Rob Walker; and Walker, impressed by the organization at Aintree, had had no hesitation in recommending Sykes.

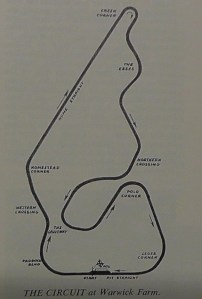

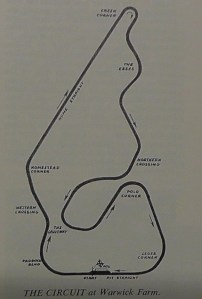

Sykes travelled by BOAC Comet to Australia for a three-week fact-finding tour, beginning in December, 1959. Staying at Tattersall’s Club in Elizabeth St, he rang Meris Rudder, who had moved to Australia following the death of her husband and had bought a small flat in Kirribilli below the north-east pylon of the Harbour Bridge. In a matter of three hours, using Meris’s living room table as a flat surface, Sykes drew what was later to become the Warwick Farm motor racing circuit. Few changes were made to the original design (which included two Aintree-inspired crossings of the horse-racing circuit).

That first draft – described by Meris at the time as looking more like a Picasso than a motor racing circuit – is today the property of Richard Sykes.

Sykes returned to Australia permanently in June, 1960, when work promptly began on the new circuit. Thanks mainly to Sykes’ planning and organizational expertise, the new facility was finished in an astonishing six months. The removable Tarmac sections for the two temporary crossings were designed and built by de Havilland (Australia) Ltd; and the design overall of the 2.25-mile circuit combined fast corners with a series of ess-bends, a double-apex, negative-camber left-hander over the lake and two tight corners – Creek Corner hairpin at the end of Hume Straight (which was parallel to the Hume Highway) and a right right-hander by the AJC Polo field. The three grandstands on the pit straight were as used for the horse-racing (as at Aintree). The circuit was noteworthy at the time for its large expanses of grass and for its white railing (from the horse-racing track). It was thus so far ahead of its time in terms of safety that Sykes felt obliged to try a “no-spinning” rule in 1964, arguing that this would be the equivalent of the trackside hazards that characterized other circuits throughout the world. Given the dangers of motor racing in the 1960s, it is remarkable that not a single driver or spectator was killed at a Warwick Farm race meeting. (One driver lost his life in a testing accident.)

The first Warwick Farm race meeting was held on December 18, 1960, and was followed soon afterwards, on January 29, 1961, by a major international race meeting that featured a 100-mile event for F1 drivers and top locals. In 110 deg F (41 deg C) heat, 65,000 spectators watched Dan Gurney, Graham Hill, Innes Ireland, Jack Brabham and the eventual winner, Stirling Moss, give the new circuit, and its organization, a massive vote of approval. Moss declared the circuit’s layout and organization to be the equal of any venue in the world. Warwick Farm was an instant success.

Sykes, who habitually wore light chino trousers, suede shoes, white shirt, club tie or cravatte, sports jacket and cloth cap, was also a man of great artistic talent and attention to detail. He personally designed the badge of the circuit’s new club, the Australian Automobile Racing Club (the AARC, instigated in July, 1961), together with the circuit’s support merchandise, including the programme covers, posters and car stickers, nominating a local artist, Peter Toohey, for much of the artwork. The AARC was from the start a small but extremely efficient operation, featuring Sykes as the General Secretary; John Stranger, formerly of the North Shore Sporting Car Club, as Accountant and Secretary of the Meetings; and Mary Packard as general administrator. They were later joined by a young school-leaver, Peter Windsor (Press Officer). The AARC was originally based at 184 Sussex Street, Sydney, but moved to the site of a former Bank of NSW, on the corner of Sussex and King streets, on June 24, 1967.

As one of the few locations in Australia where you could “talk motor racing” and read the latest publications from the UK (Motoring News and Autosport), the AARC offices quickly became a Mecca for both famous racing names and rank-and-file club members. The AARC staged four to five major race meetings at Warwick Farm per year, including the February international, three or four club meetings (on a shorter circuit that looped back to the Causeway after the first corner) and numerous members’ film nights – these providing the only opportunity for motor racing enthusiasts in Australia to see the latest images from overseas.

On February 10, 1963, Warwick Farm hosted the Australian Grand Prix for the first time. Again run in extremely hot conditions, it was reported in Autosport by Sykes himself, who wrote, “Race week was a busy one from a social angle, and there was for the first time in Sydney an atmosphere of Grand Prix fever… On Thursday the AARC put on their second annual cocktail party with an attendance of 550, and regrettably had to turn down almost 200 would-be attenders….both Stirling Moss and Graham Hill gave brilliant dissertations rather than speeches…Graham Hill also had his Datsun Bluebird towed away from outside Geoff Sykes’ office – it costs £4 10s to get it back in Sydney!…The meeting was voted the best so far at Warwick Farm, and all the officials did a magnificent job to keep everything going like clockwork under such trying conditions – full marks to all those with the thankless jobs.”

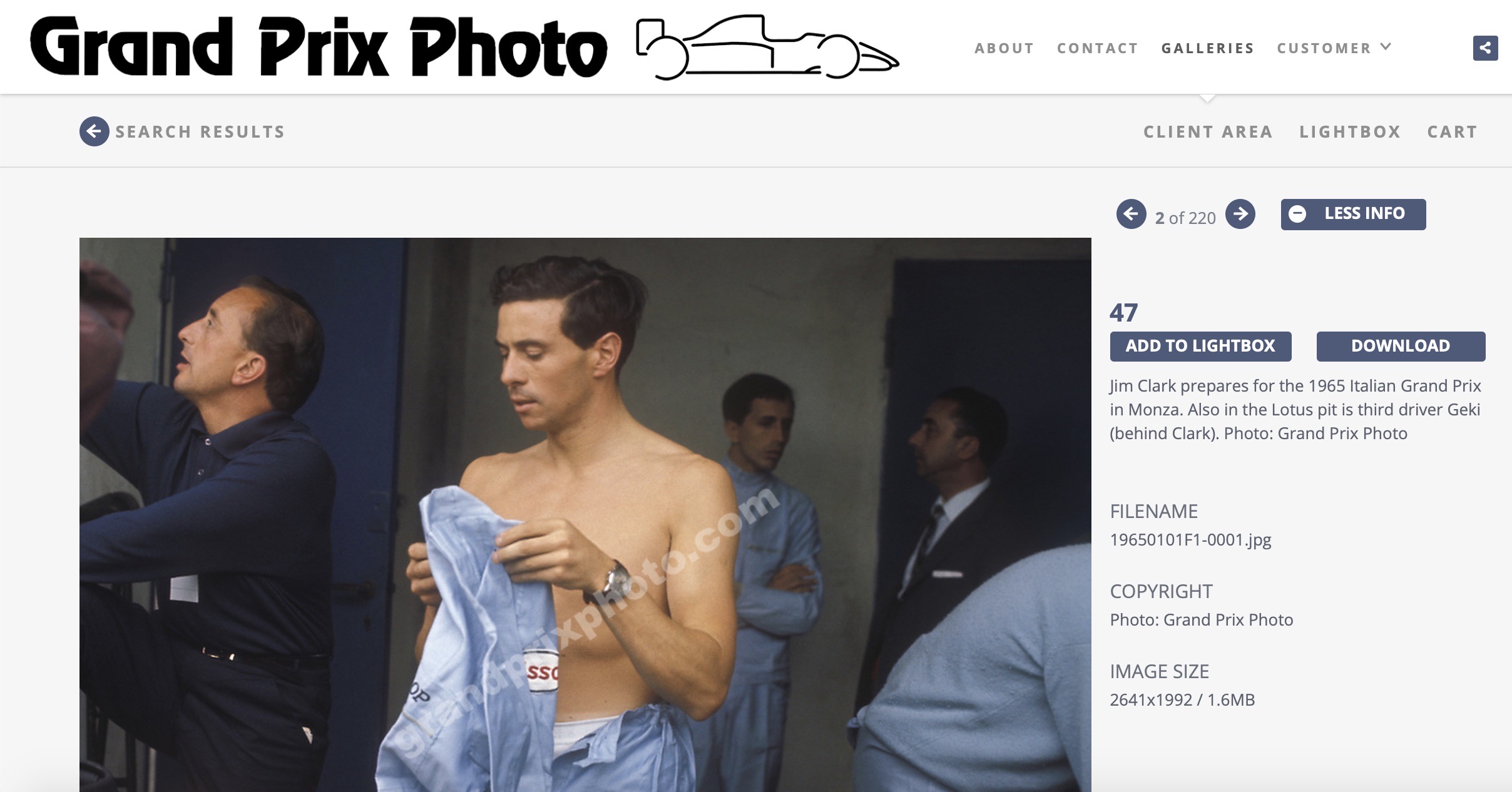

Sykes and his New Zealand counterpart, Ron Frost, initiated a new Tasman Cup in 1964, taking the Antipodean summer international series to even greater heights. As the promoter who had the unique respect of the major F1 teams and drivers, Sykes travelled to Europe each year to negotiate their appearances (a trip usually timed to allow Sykes to indulge his love of aircraft at the mid-July Farnborough Air Show). Sykes and Jim Hazleton helped the great Scots driver, Jim Clark, learn to fly at Bankstown airport in 1965; and the AARC would go on to own several light aircraft for the use of its members – a Cherokee 140 (registration VH-ARC), a Cessna 172 (VH-ARA), a Cherokee 180D (VH-ARD) and latterly a Beechcraft Sundowner (VH-ARF). Sykes also flew his own low-wing Thorp T111 Skyscooter out of Bankstown, registration VH-DES.

As the promoter who had the unique respect of the major F1 teams and drivers, Sykes travelled to Europe each year to negotiate their appearances (a trip usually timed to allow Sykes to indulge his love of aircraft at the mid-July Farnborough Air Show). Sykes and Jim Hazleton helped the great Scots driver, Jim Clark, learn to fly at Bankstown airport in 1965; and the AARC would go on to own several light aircraft for the use of its members – a Cherokee 140 (registration VH-ARC), a Cessna 172 (VH-ARA), a Cherokee 180D (VH-ARD) and latterly a Beechcraft Sundowner (VH-ARF). Sykes also flew his own low-wing Thorp T111 Skyscooter out of Bankstown, registration VH-DES.

Due to the long time they had spent apart on different sides of the world, Geoff and Margaret divorced in September, 1966. Four weeks later Geoff married Meris Rudder.

Warwick Farm staged the Australian Grand Prix on four occasions – 1963 (won by Jack Brabham); 1967 (Jackie Stewart); and 1970 and 1971 (Frank Matich). Sykes introduced the extremely popular, and affordable, Formula Vee cars to Australian motor racing (two Vees and a Formula Ford were owned by the AARC for the use of club members); pioneered the concept of the club race meetings and practice days; and, in the 1970s, was also one of the key figures behind the choice of production-block Formula 5000 cars for Australia’s premier single-seater category. The AARC continued to promote successful and well-attended national race meetings through to July, 1973, when the AJC decided that the land used for most of the motor racing circuit should be sold for property development. Sykes and the AARC (primarily through the work of Mary Packard) then assisted with the promotion of club race meetings on the smaller Warwick Farm circuit (through to October 28, 1973) and then at Amaroo Park (through to November 30, 1986). Living with Meris in the original Kirribilli flat, Geoff in his retirement spent much of his time with bikes and cars: he enjoyed restoring historic motor-cycles and riding his vintage Velocette; and, following a succession of white, automatic Triumph 2000s, drove a yellow Alfa Romeo GTV.

Warwick Farm staged the Australian Grand Prix on four occasions – 1963 (won by Jack Brabham); 1967 (Jackie Stewart); and 1970 and 1971 (Frank Matich). Sykes introduced the extremely popular, and affordable, Formula Vee cars to Australian motor racing (two Vees and a Formula Ford were owned by the AARC for the use of club members); pioneered the concept of the club race meetings and practice days; and, in the 1970s, was also one of the key figures behind the choice of production-block Formula 5000 cars for Australia’s premier single-seater category. The AARC continued to promote successful and well-attended national race meetings through to July, 1973, when the AJC decided that the land used for most of the motor racing circuit should be sold for property development. Sykes and the AARC (primarily through the work of Mary Packard) then assisted with the promotion of club race meetings on the smaller Warwick Farm circuit (through to October 28, 1973) and then at Amaroo Park (through to November 30, 1986). Living with Meris in the original Kirribilli flat, Geoff in his retirement spent much of his time with bikes and cars: he enjoyed restoring historic motor-cycles and riding his vintage Velocette; and, following a succession of white, automatic Triumph 2000s, drove a yellow Alfa Romeo GTV.

After several years of battling a heart condition, Geoff died on April 12, 1992, at Royal North Shore Hospital, North Sydney.

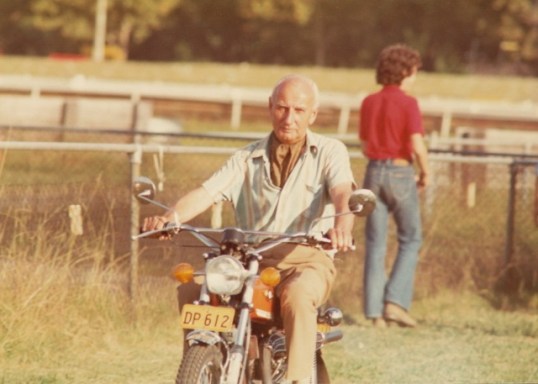

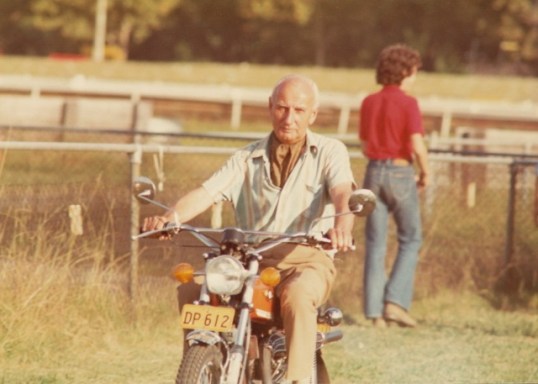

Captions from top: Jim Clark drifts the Gold Leaf Lotus 49 through the Warwick Farm Esses during practice for the 1968 International 100; Geoff takes Colin Piper’s new Suzuki for a quick spin around the Warwick Farm paddock; the Farm circuit changed not at all from Geoff’s original sketch; Jim Clark (left) and Jackie Stewart share a laugh. The “chair” is Graham Hill’s new F2 Lotus 48, the background is the Causeway lake; Kevin Bartlett dances through Leger Corner in the Mildren Alfa; and (above), the AARC cloth badge

Photos: Paul Hobson, Colin Piper

Posted in

Circuits,

Days Past,

F1,

People,

The Tasman Series and tagged

AARC,

aintree,

australia,

barc,

Goodwood,

Jackie Stewart,

Jim Clark,

mrs topham,

sydney,

tasman series,

Warwick Farm