World Champion in 1967, Denny Hulme (pronounced Hull-m) was an engineer-driver in the mould of Sir Jack Brabham. He was fast; and he was blessed with extraordinary car control. Denny was also very sharp. In the days when you were allowed to do it, Denny would often start a race with a different tyre compound on each corner of the car. Two-thirds of the way through the distance, there would be Denny, reeling-in the leaders… He got his hands dirty, too: he was one of the boys. I was a huge Denny fan when, as a kid, I saw him race in Australia. Through the Warwick Farm esses he’d slide the Brabham from lock to lock, Bell Star, facemask, goggles and Goodyear race suit resplendent in the summer sun. And then you’d run back to the pits to see Denny in de-brief mode, coiled around an awning, talking about spring rates or roll-bars.  When I took the plunge to try my luck as a motor racing journalist, my first assignment was to cover the 1972 South African Grand Prix for Autosport. I flew across to Johannesburg from Sydney. I was disoriented and intimidated. And then I saw Denny. Suddenly, everything felt right with the world. I asked him about the McLaren M19, which was racing that weekend for the first time in Yardley colours. I asked him about the other cars, too. Although he was by then a World Champion of enormous stature, Denny was straightforward and welcoming. And, on the Sunday, he won the South African Grand Prix, heading a one-three finish for the Colnbrook team. Here are my notes from that race (first published in McLaren’s official F1 website):

When I took the plunge to try my luck as a motor racing journalist, my first assignment was to cover the 1972 South African Grand Prix for Autosport. I flew across to Johannesburg from Sydney. I was disoriented and intimidated. And then I saw Denny. Suddenly, everything felt right with the world. I asked him about the McLaren M19, which was racing that weekend for the first time in Yardley colours. I asked him about the other cars, too. Although he was by then a World Champion of enormous stature, Denny was straightforward and welcoming. And, on the Sunday, he won the South African Grand Prix, heading a one-three finish for the Colnbrook team. Here are my notes from that race (first published in McLaren’s official F1 website):

Jan Smuts airport felt very like Sydney’s Kingsford Smith in early March, 1972: officials wore shorts, long socks and khaki shirts with epaulettes. A bright sun shone through the glassy structure. Outside, as I queued for a taxi, there was a smell of eucalyptus in the air. And so I relaxed. It would be all right. I could to this. It was just like home. I gathered my baggage – one suitcase into which I had crammed my life – plus the Olympia portable typewriter I had bought a few days before, after the last Tasman race, from the talented New Zealand journalist, Donn Anderson. “The Kyalami Ranch hotel,” I said, brimming with anticipation, to the driver of the Ford Falcon taxi.

And so my F1 life began… I had met my new boss, the journalist and photographer, David Phipps, two months before, in London. I had asked him for a job. He had written to me a few weeks later, suggesting I fly from Sydney to the UK via Kyalami, where I could write about the South African Grand Prix for Autosport. I sold everything I owned – a Honda trail bike and a Komini (fake Bell) helmet; I cashed in my savings ($A725); I bought an air ticket with SAA; and I said good-bye to my family, friends and to our basset hound, Conkers. I had no idea when I would see any of them again. I was 19 and I was hoping – some day, probably 50 years away – that I would be lucky enough eventually to make it as a professional F1 journalist. I don’t think I’ve ever been more nervous than when the taxi pulled into the driveway of the Kyalami Ranch. I paid the driver. I unloaded my bag. I walked towards to the hotel’s check-in building, perspiring in the heat – and there, to my right, I saw them: on the grass by the pool, in swim-suits, sat Mario Andretti, Clay Regazzoni and Jacky Ickx. And there – over there! – was Graham Hill. And wasn’t that Francois Cevert, in blue swimming trunks, walking towards the pool? Room 164 was on the far side of the compound. Sweating freely now, and drained from the long trans-continental flight in the 707, I timidly walked away from the crowd, out towards the trees by the back fence. Along the way, on my left, tapping furiously at his typewriter, I recognized the great Heinz Pruller, close friend of the late Jochen Rindt and world-famous writer. Was that how I was going to have to type? What was he writing anyway, this early in the week? What did he know that I didn’t? Doubts clouded my mind; I felt like turning around and going home.

Then, drowning the tapping, I heard the faint sound of an F1 engine. It was the bark of a tickover at first; then there was the up and down shrill of a Cosworth DFV at play. I stopped and looked over to the hill in the distance, straining my eyes in the glare. Yes! I could see the outline of the circuit in the veldt. The main grandstand was a silhouette against the African sky. I rushed to my room, inhaling the smell of air conditioning, humidity and hot foliage that in years to come would become so familiar in summer-race climates. I quickly showered and changed into shorts and shirt. And then I walked back again towards the pool. David Phipps – tall, schoolmaster-like, strode towards me. “Welcome to South Africa. Good flight? Come over here and I’ll introduce you.” “Colin? This is my new assistant, Peter Windsor. He’s going to be helping me with reports this year. He’s just flown in from Australia.” “How do you do,” said Colin Chapman easily. “Well. You’re making a good start. David Phipps is the best newsman in the business.” “Emerson? Are you going to be testing later?” asked David. I looked across at the sunbeds next to Chapman. Emerson lay there, browning in the South African sun, black and gold sunglasses offering only tertiary protection. Peter Warr strolled up, wanting to talk to Colin about Dave Walker. I pretended not to listen. Then David Phipps walked me over to the Ferrari group. “Mario. This is Peter Windsor. He’s helping me this year.” I spoke for the first time. “Very pleased to meet you, Mr Andretti. And congratulations on your win here last year. How’s the car going so far?” “Not as well as in 71, I can tell you that,” replied Mario…and I was off. A conversation had begun.

Later that afternoon, at about 4 o’clock, David drove up to the circuit. I walked eagerly up to the garages, spying Elf Team Tyrrell on the left. I looked in to see the legendary Roger Hill changing gear ratios on Cevert’s car. The familiar smell of brake fluid and WD40 reminded me of F5000 races in Australia. This was different, though. These were the royal blue Elf Tyrrells of the World Champions. This was the top of the mountain. “Hi,” I said. “I’m reporting my first race for Autosport. I was wondering whether you’re going longer or shorter with the ratios…?” “Hello there,” said Roger. “Come in. We’re actually going longer. Jackie usually starts a little taller than Francois and so we’re going in that direction. I’m a bit busy now but come back a bit later if there’s anything I can help you with…” That night, forgetting sleep, and trying to imagine how DSJ (Denis Jenkinson) of Motor Sport would approach it, I started to write about the “entry” for the South African Grand Prix. When I look back at it now, I think “boring” probably best sums up my work, so I won’t reproduce too much of it now. Why was it like that? I didn’t try anything new – and Mel Nichols, of Haymarket, had yet to introduce me to the free-flowing style of Rolling Stone or Tom Wolfe’s The New Journalism. Up-and-down was all I knew – and all, I guess, that anyone ever expected. I wrote within the straitjacket that I assumed was de rigeur in F1. Thus I said things like the following:

Entry

After the Argentine Grand Prix all the cars, with the exception of the Ferraris, were flown directly from Buenos Aires to Johannesburg and it was thus hardly surprising to find that the entry for the sixth South African Grand Prix was substantially unchanged (except for the addition of three local cars). (“The Entry” section of reports in the 1970s was always an important, opening phase: back then, teams were not obliged to enter every race and were also free to enter one, two, three, four or even five cars if they so wished.) At the extreme left of the long lock-up garages were Elf Team Tyrrell, where the two regular Tyrrell-Fords, Stewart’s 003 and Cevert’s 002, were joining 004, which had been at Kyalami for several weeks for Goodyear tyres tests. Stewart’s best during those tests had been 1min 16.4sec, and this was the mark for which everyone aimed during official practice (as qualifying was known back then). Adjacent to the Tyrrell team were STP-March, with two Ford-engined 721s for Ronnie Peterson and Niki Lauda. Both cars were fitted with the shovel-type noses first tried by Peterson during practice for the Canadian Grand Prix last year; effective though they were, they looked as though they had been intended for a different car. The only major change on the Yardley McLaren-Ford M19As was a new type of adjustable mounting for the rear wing. Both Denny Hulme and Peter Revson had been testing in the week before the race but had been handicapped by wet weather. Etc, etc.

In the day that followed, and into Saturday practice, I spent most of my time with John Surtees and Mike Hailwood, Denny Hulme and Teddy Mayer, of McLaren, Keith Greene at Brabham, Alan Challis at BRM, Frank Williams and Colin Chapman. All were very nice to me – mainly, I suspect, because of David Phipps’ reputation in the pit lane. I also managed to strike up a three-minute conversation with Carlos Reutemann, along the lines of, “why did your tyres go off so much in Argentina?” Peter Revson, super-cool with a Gulf logo on his Hinchman overalls where Denny wore the Yardley badge, was also an easy guy with whom to talk: “Great helmet design, Peter.” “Thanks. I worked on it for quite a while before we got it right.” How’s the car feel?” “Great. This is a very good race car. We need to get the set-up right, and there’s a bit of a cooling problem, but I think we’ll be very quick all year….” There were about ten international journalists at the race and quickly they became friends. Heinz Pruller. Dieter Stappert of Powerslide (what a great name for a magazine!). Helmut Zwickl – another talented Austrian. Gerard Flocon, of l’Automobile. Bernard Cahier, of course, with his Goodyear connections. Eoin Young. Barrie Gill. Johnny Rives of l’Equipe. Gerard Crombac. Jeff Hutchinson. Michael Bowler. Andrew Marriott. As daunted as I was by their expertise and professionalism, I was able to watch them and to learn. I didn’t dine at the Ranch in the restaurant; I didn’t dare. Instead, I wrote my practice report on the Saturday before the race.

Practice

Practice was officially scheduled for Wednesday, Thursday and Friday afternoons but unofficial testing was allowed each morning and many drivers made good use of it. This is one of the reasons why Kyalami is so popular with the teams and why the circuit is given high marks by the GPDA every year. The tyre situation was more confused than ever, for Goodyear had yet another new system of numbering and had a selection of compounds made in both Wolverhampton and Akron. Firestone, on the other hand, were depending mainly on compound 1123, and didn’t seem to have enough tyres to go round. Within the first 20 min of practice on Wednesday Denny Hulme recorded a 1min 18.4, which remained the best time for quite a long while. Towards the end of the session, however, Stewart went out on his “best” tyres and recorded a 1min17.0, which left him substantially fastest. Both Ickx and Regazzoni seemed happy with their Ferraris but Andretti found his car rather unpredictable through the corners. “It’s like a yo-yo out there,” he told me.

Peterson was in trouble with an overheating engine (the same engine that overheated in Buenos Aires!) and thus had a new one fitted for Thursday. Cevert was going well, being third-fastest behind Stewart and Ickx and 0.1sec ahead of Fittipaldi. Hulme shaved 0.3sec towards the end to finish with 1.18.1 but team-mate Revson was troubled by overheating; he, too, was given an engine change. Early on Friday morning the Surtees and McLaren teams were out testing. They were later joined by Stewart, who did a glorious practice start with long, black streaks of rubber on the road – which were then closely examined by Derek Gardner. Schenken was running a new engine and was down to 1m18.2 but Hailwood did three sensational 1.17.3s in a row, which was encouraging indeed for Team Surtees. As soon as the final official practice began Hailwood went straight out and repeated his effort, finishing with an official 1.17.4. Hulme, also looking very determined, was soon down to 1.17.4, although a nasty noise from his engine precluded any improvement. Gethin was throwing his BRM around, and had a graceful spin on the exit from the tight left-hander, Clubhouse. With ten minutes of practice remaining, Stewart put in two beautiful laps at 1,17.4. On the pit wall, though, Roger Hill showed his man a “17.1 Fitt” sign, inducing the World Champion to shave a further 0.4 sec from his time. As it turned out, Emerson was credited only with a 1.17.4, so the pole was comfortably Stewart’s. Clay Regazzoni, now very happy with his Ferrari, beat Fittipaldi by 0.1 sec – and Hailwood and Hulme filled row two; but for his mechanical problems, Hulme would certainly have been faster. Revson’s bad luck continued, forhe drove a drive-shaft while practising a start; that left him on the fifth row with Amon and Beltoise.

I awoke early on race morning, nervous and feeling inescapably as if I was drowning: the race report had to be finished in neatly-presented typed manuscript within two hours of the chequered flag. I – or possibly an official from the Telex agency – would then have to re-type it into a Telex machine at the track. There was only one Telex in the Kyalami press office and plenty of other journalists, I knew, would be vying for its use.

David, meanwhile, was more concerned with sending the black-and-white images back on the first available flight. I had to make phone calls to the freight shipping agents and to ensure that at least a couple of rolls of film went back with Colin Chapman – who would have to be met at Heathrow, of course. I did, though, drop by the restaurant before we left for the circuit. David was easy to identify. I walked over, between the packed tables, trying not to bump anyone with my Qantas shoulder bag. It was only when David was clearing a space for me, and pointing to a chair, that I realized he was breakfasting with Denny Hulme, who was wearing a striped blue polo shirt and shorts. I froze momentarily, then tried to be calm. Denny just kept on talking: “….it took forever, but I think we’ve got it about right now. I’ve got the brake discs flush to the ceiling and the actual light cord passes through the centre of them….” It was only when I visited Denny in his house in Walton-upon-Thames, Surrey, later that year, and noticed the ventilated McLaren M8D disc brakes forming the light clusters, that I realized what he had been talking about. Denny had a way of being completely normal and matter-of-fact. I was able to ask him one or two questions during our breakfast at The Ranch and from that moment onwards I always found him to be courteous, informative and extremely intelligent. He wanted people like me to understand what he did for a living. He wasn’t interested in the trimmings that came with his job. He just loved sorting out a car and then driving it. And Denny was fast; have no doubts about that.

David and I left for the circuit about an hour later. The crowd was huge – 95,000. We turned off early, by the “Officials” sign and lined up behind the Goodyear boys in their rental car, ready to show our paper passes. Then, from nowhere, came a little piece of heaven. Two South African girls – gorgeous both – were dressed in Yardley short-sleeved shirts and hotpants. And what was this they were giving out? Little bottles of Yardley after-shave! I pleaded for two bottles, perhaps three. I had never seen this stuff in my life – not in my Australian life. I removed the little black cap and drunk the aroma. Spicey, clean and intoxicatingly memorable. For me, this scent would always be synonymous with Kyalami, McLaren and a hot summer’s day. Sadly you can’t buy this mixture any more, although I still have the Yardley McLaren stickers the girls also gave us that morning. I felt I had to mention all this in the Autosport report. I should also add that this race was held on Saturday, thereby enhancing the texture and depth of the occasion. This was South Africa – one of the greatest of all sporting nations – devoting its “day of sport” to Formula One. None of that “cricket on Saturday, motor racing on Sunday” stuff; this was a head-on commitment to the South African Grand Prix. To the Suid-Afrikannse Grand Prix.

Race

Even on Friday night the race crowd poured into Kyalami and by Saturday morning the undulating, well-equipped circuit was a mass of parked cars and people, most of whom had received Yardley after-shave and Lucky Strike posters as they passed through the gates. For those that wanted it, there was another untimed practice from 11:30 to midday, during which Revson’s left-front wheel came off and Hulme’s new engine (retrieved from the airport on Friday night) suffered another damaged rear oil seal. Alastair Caldwell and the boys set to work with resigned application. As 3:00pm approached the cars were wheeled around to the front of the pit counter, most of them on wet weather tyres to avoid the chance of punctures. There was just one warm-up lap and then the field lined up on the dummy grid.

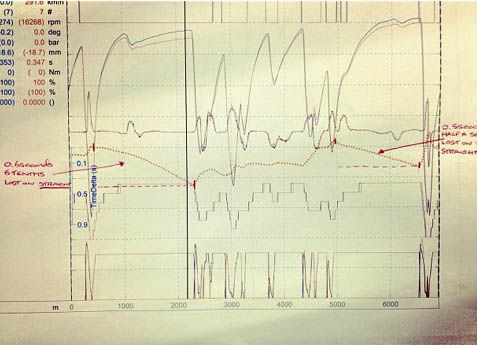

They moved forward with 30 seconds to go, led by Stewart. It was Fittipaldi and Hulme who timed the start perfectly, though, anticipating the flag-drop almost to the millisecond, and, in Denny’s case, perfectly managing double-dip clutch slip against revs. Further back, a lot of mid-field dodging took place down the long straight as Revson (wary of another drive-shaft problem) was very slow away. There was further drama as they crested the rise just before the Dunlop Bridge. With the screaming pack in sight, two cretins ran across the track from the outside. They made it safely to the grass verge on the but it was shocking to see – and must have been sickening for those at the front – for Hulme, Stewart and Fittipaldi. Denny seized the inside for Crowthorne, braked ultra-late and decisively snatched the lead. Stewart filed into second place, followed by Emerson and Mike Hailwood in the Surtees. I was standing on the bank between the exit of Clubhouse and the acceleration run from Leeukop down the long straight. The white McLaren led the snake of cars out of Sunset, Denny jinking the steering on exit, Stewart tucked right up behind him. Then noses dipped under heavy braking for Clubhouse. Downshifting and crackling exhausts. Then more opposite lock, as Denny, on full tanks, massaged the oversteer. No-one crossed arms as much as Denny – but there was a certain grace to his movements, a certain touch. A certain feeling of “this car is still dead-square to the road, even if it is travelling a little sideways”. The trail of cars disappeared as they plunged into the esses – but then Denny’s McLaren soon re-appeared in the distance on the uphill approach to the Leeukop right-hander. Nose down, then nose up. Denny was clear and away, leading the pack through third, fourth and fifth – onto the long finishing straight.  As Hulme braked for Crowthorne on lap two, Stewart’s blue Tyrrell dived down the inside and seized the lead. Jackie was able to eke out a slight advantage, too, while, behind, the racing remained hectic: the field formed a long train, with positions changing rapidly and cars often side-by-side as well as nose-to-tail. Through it all came Peter Revson, slicing his way through the field with brilliant precision and judgment. Could McLaren’s troublesome weekend suddenly be falling into place? Sadly no. Emerson Fittipaldi displaced Hulme on lap 16, for Denny’s engine was again beginning to overheat. He backed off the revs – from 10,500 to 10,000 – and watched the Lotus 72 pull away from him, remorselessly into the slipstream of Stewart’s Tyrrell. Next into the frame came Mike the Bike Hailwood, loving the feel of the Firestone-shod Surtees and looking as neat and as tidy as Stewart at this very best. Mike, too, passed the ailing McLaren – and closed quickly on Stewart and Fittipaldi.

As Hulme braked for Crowthorne on lap two, Stewart’s blue Tyrrell dived down the inside and seized the lead. Jackie was able to eke out a slight advantage, too, while, behind, the racing remained hectic: the field formed a long train, with positions changing rapidly and cars often side-by-side as well as nose-to-tail. Through it all came Peter Revson, slicing his way through the field with brilliant precision and judgment. Could McLaren’s troublesome weekend suddenly be falling into place? Sadly no. Emerson Fittipaldi displaced Hulme on lap 16, for Denny’s engine was again beginning to overheat. He backed off the revs – from 10,500 to 10,000 – and watched the Lotus 72 pull away from him, remorselessly into the slipstream of Stewart’s Tyrrell. Next into the frame came Mike the Bike Hailwood, loving the feel of the Firestone-shod Surtees and looking as neat and as tidy as Stewart at this very best. Mike, too, passed the ailing McLaren – and closed quickly on Stewart and Fittipaldi.

The racing was superb, the standard of driving sublime. Back-markers began to play their part. Some obeyed flag signals; others did not. Mike and Jackie were side-by-side as they flashed past the grandstands on lap 27, although Jackie retained the lead. Then, on lap 29, Hailwood’s strong challenge was over as quickly as it had begun. A lower rear wishbone mounting broke as he turned in to the very fast Barbeque Bend. The moment was almost as nasty for Emerson, who was following closely, as it was for Mike. Brilliant reflexes saved the day. By lap 30, then, you could have been excused for thinking that the pattern was set. Stewart led Emerson by 2 seconds, with Denny still third. Revvie was now up to sixth; ahead lay the rapid Matra of Chris Amon. Ferrari, though, were in trouble on this high-altitude circuit: they were running lean mixtures to try to manage fuel loads but all three engines were now way down on revs as a result. Reliability had plenty of hands to deal to other teams, too.

On lap 45, to the astonishment of all, Stewart cruised into the pits with no oil in the gearbox: a drainage bolt had worked loose. Emerson now led by 4.5sec from Denny, with Ronnie Peterson third, Amon fourth and Revvie fifth. Then Emerson, too, struck trouble: his 72 began to oversteer dramatically on all types of corners – and particularly through Sunset, where Emerson’s balance was stunning to watch, lap after tyre-consuming lap. He kept on fighting, nursing what turned out to be badly worn rear Firestone 1123s, but now Denny could smell blood. His Goodyears in perfect shape, Denny flicked to the inside on the approach to Crowthorne on lap 56. He won the corner; and immediately (to his surprise) began to pull away. For two laps he continued to rev to 10,000. Then, remembering the last-minute suspension failure that had robbed him of victory at Kyalami the year before, he backed off to 9,500. Amon stopped briefly to complain of a vibration. A broken rear wing stay on the March obliged Ronnie Peterson to add new meaning to the term “opposite lock”.

And into third place, therefore, strode Peter Revson. Had he had a better run in practice – or had he not dropped down to 18th on the opening lap – Revvie might even have been second. As it was, he registered the first top-three finish of his career. There was no stopping Hulme and the Yardley McLaren in the closing laps. The 1967 World Champion took the flag 14.1sec clear of Emerson, from Revvie and Andretti, who had driven another good race for Ferrari in difficult circumstances. On the podium, facing the grandstands, Denny held the huge, silver trophy aloft. They clamoured round about him: even Barrie Gill was there with microphone and cameraman, eager to grab a soundbite for the TV news. Of Emerson and Revvie, though, there was no sign, for at Kyalami, as at many other circuits, only the winners receive the plaudits.

I set about my report. I found a table in the press room. I wound the first sheet of white paper into my beloved Olympia. I fitted ear plugs. And I asked myself the question: “What would I want to know about this race if I’d heard only the results? I didn’t have all the answers; I would never have all the answers. I could, though, at least make a start. Denny Hulme, the driver with whom I had had breakfast, had won the South African Grand Prix. Now it was up to me to me. I needed to do justice to the day – and to David Phipps, who believed in me. Quickly. And without hesitation. That was what I told myself as I sat there, amongst Pruller and Crombac, Flocon and Zwickl. That was what I told myself as I watched those masters at work.”

Pictures: SuttonImages (David Phipps Archive) and The Peter Windsor Collection