peterwindsor.com

…chance doesn't exist; there's always a cause and a reason for everything – Elahi

Archive for the tag “Ferrari”

Gilles – in the mould of Nuvolari

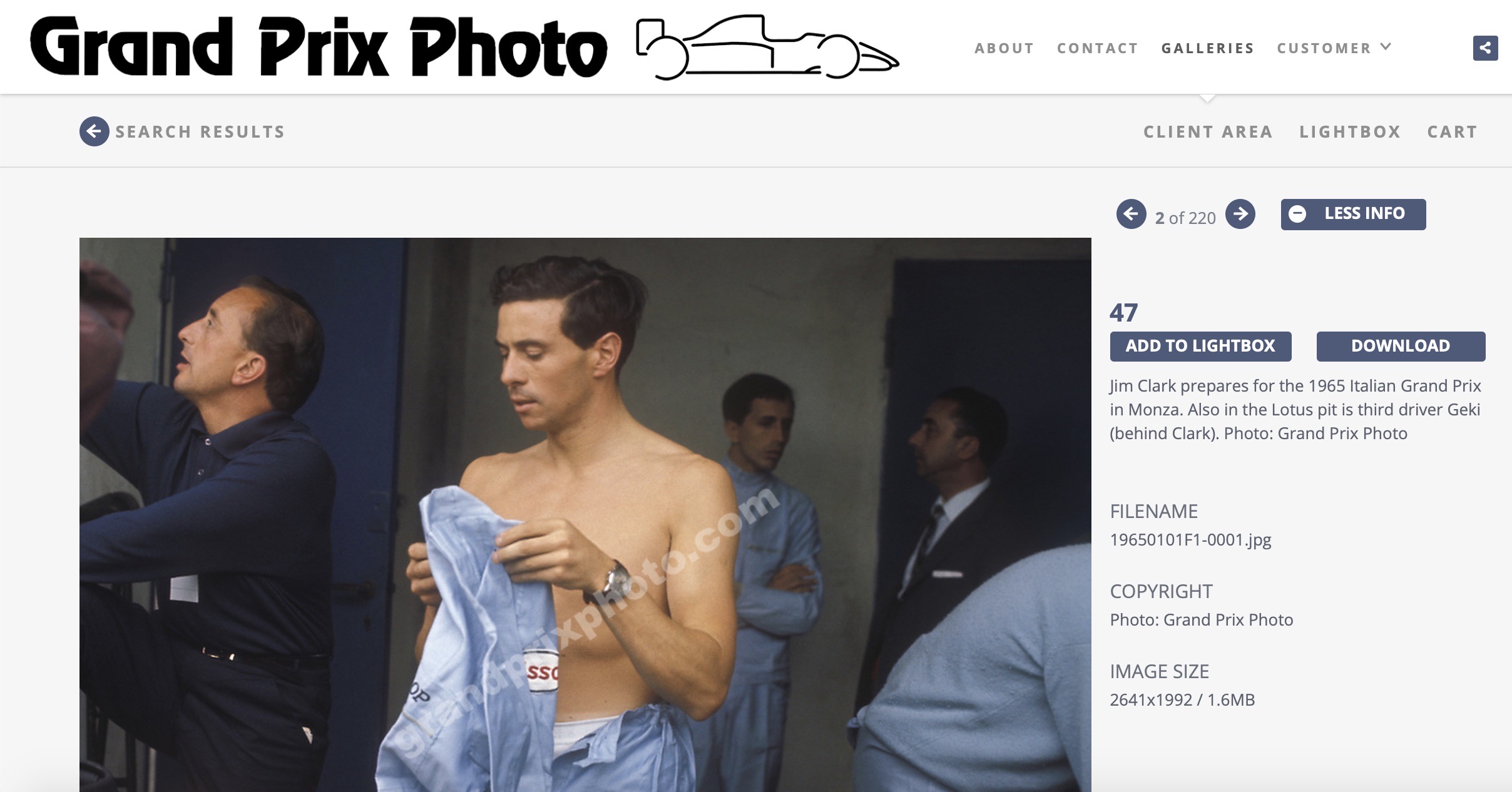

We enjoyed his supreme, audacious talent for only a few, dazzling years. And then the shining light was gone, extinguished by a stupid rule that obliged drivers like Gilles to take additional risks…as if there weren’t enough already. Thirty years on, here are a few of the photos I took of my friend – and some notes I made in May, 1982.

Brazil, 1982: spying a camera around my neck, Gilles grabbed it and snapped this self-portrait

I was standing by the phone booth in the Zolder paddock on Friday afternoon when I saw Gilles, lost in a big, yellow Ferrari transport van, sitting up there in the passenger’s seat. I waved. He beckoned the driver to stop and wound down the window.

“Which hotel are you in?”, he asked.

“The Mardaga,” I replied. “Quite close to the track.”

“Ok. Don’t worry. I thought you might like a lift to the Post House. I’ve got the new Augusta here. You haven’t had a ride in it yet, have you?”

I hadn’t, although my next project was certainly to fly to a race with Gilles. It was his idea. He wanted everyone to enjoy his new baby.

With that, Gilles drove away. I never spoke to him again. The next day, he fell victim of exactly the sort of racing accident he had been forecasting. He was on a flying lap; there were ten minutes of qualifying remaining; and he was on his third (“mixed”), last, set of qualifying tyres. Didier Pironi, his “team-mate”, had annoyingly just bettered Gilles’ time by 0.1sec. In total, 30 cars were running. What with the qualifying tyre situation, and the lightweight Cosworth cars, there were more guys out there, cruising the lap, than there were cars going quickly. The day before, Gilles had been irritated yet again by the traffic problem. “It’s no worse that usual, I guess – which means it’s very bad. Every time I was on a quick lap I came across someone going slowly. Like I’ve said a million times before, it’s crazy being allowed only two sets of tyres. You’re forced to take ridiculous risks.”

In one such incident that Friday, Villeneuve had to brake hard to avoid running into the back of Jochen Mass’s March. Indeed, the Ferrari incident report from that day, in a tragically prophetic statement, said: “The French Canadian expressed himself absolutely amazed at the ‘early braking’ habits of some of the slower drivers, and confessed to having a couple of nasty moments when he nearly collected a Renault and a March…”

So it was the following afternoon. Villeneuve, on the limit and heading for a quick time, crested the rise after the first chicane to find Jochen Mass’s March ahead of him. Jochen says he was going slowly – in fifth gear, but certainly not flat through the left-hand kink and the short straight that follows it. “I saw Gilles in my mirrors,” he said later, “and expected him to pass on the left. I moved right and couldn’t believe it when I saw him virtually on top of me. He clipped my right rear tyre, bounced off the front and was launched into the air…”

Mass went on to say that he could imagine how Gilles had reacted. He was on the limit, there was a slow car ahead of him, he didn’t want to back off and he had to make an instant decision – left or right? “I have been in a similar situation at that place before,” said Mass. “It’s difficult, because although it’s a left-hand kink it’s possible to get by on the outside. He obviously chose to go on the outside and there wasn’t room.”

From Gilles point of view, of course, it would have been much less decisive. He would have seen Mass in the middle of the road – would probably have thought about Friday for a millisecond – and then he would have had to have made an instant call about which side Mass was going to move. With a left-hand kink approaching, he obviously thought Mass was going to move over to the inside. Thus Gilles went to the right. Thus the impact.

Travelling as slowly as he was – particularly in the closing minutes of qualifying – Mass in my view should have been either on one edge of the road or the other and making it very clear on which side he wanted to be passed. Critics of Villeneuve say that he had the option to back off if he was unsure; as Gilles said so many times, however, the pressure of running only two sets of qualifiers behoved the drivers to take risks and to gamble. And on Gilles the pressure was even greater: he was virtually a lone crusader against the danger of running only two sets of qualifiers. All the other drivers, wary of stirring the waters, remained more or less quiet.

The impact, when the 126C hit the ground, was catastrophic. The seat belts pulled out of the rear bulkhead of Harvey Postlethwaite’s carbon-aluminium chassis and Gilles, still in his seat and holding the steering wheel, was thrown onto the side of the track through two layers of catch fencing. Gilles’ GPA helmet – fastened around its based by a “hinge” system – came off and rolled to a halt a few feet away. From the point of impact with Mass’s March, the Ferrari had flown and crashed through a debris field about 150m long.

Mass stopped. So did Didier Pironi. Mass led Pironi away. And then, ten minutes later, Gilles was flown by helicopter – not his own – to a nearby hospital. He was gravely injured, unconscious but showing vital signs.

He had no chance, though. He passed away shortly after 9 o’clock that night.

So it was over. Just like that. A stupid accident caused by hitting a slower car – although the real cause, as Mass pointed out, was the lunacy of having to use only two new sets of qualifiers. Eddie Cheever would talk endlessly about how close Gilles came to hitting him at Rio. And, in South Africa, during the drivers’ strike, increasing the number of qualifying tyres was Gilles’ Number One topic of conversation. The other drivers soon tired of it all.

Just as we had to await Niki Lauda’s accident to see how right he was about the Nurburgring, so it was left to Gilles, in the saddest of ways, to demonstrate the point about qualifiers. Too late, the future would have much to say about the tyre rules. Racing, meanwhile, lost its heart and its soul.

There was no question that Gilles was on edge during practice at Zolder. The comments he made about Pironi after Imola showed no signs of mellowing. He was incensed even more by the people who had since declared Imola “a great race”! “That wasn’t racing,” he said with disgust on Friday at Zolder. “Every time I backed off Pironi passed me. Then I had to fight back to take the lead. I don’t call that a race…”

Gilles walked around the Zolder paddock quickly, pointedly. The days of laid-back Gilles were over. From everything he did, from jumping from the back of the new pits complex to the roof of the Ferrari transporter, or sitting impassively in his 126C, arms folded, while mechanics prepared the car for his final, flat-out run, you got the impression that Gilles was saying, “Right. The playing is over. From now on I take no prisoners.”

And so Gilles, in those last few days of his life, engendered the one thing he had always lacked – ruthlessness. Before Imola he was full of praise for his “team-mate”. He even came to Pironi’s defence when Joanne pointed out that it was quite rude of Pironi not to have invited Gilles to his wedding. “He probably just forgot,” said Gilles, ever the noble soul. In 1978 Gilles had been humble enough to say that he was “delighted” to be Number Two to Carlos Reutemann at Ferrari. Ditto in 1979, when he agreed before the Italian GP to let Jody Scheckter win the Championship, even though he, Gilles, was still right in the title race with a serious chance. “Don’t worry, Jody. You can help me win it next year,” he said. The next year, though – 1980 – the Ferrari turned out to be a dog. A lazy dog. Of course Gilles believed that he was quicker than Pironi but never, prior to Imola, would he concede that Pironi was any sort of threat – political or otherwise.

After Imola, that changed. Tougher than ever, Gilles was in the process of consolidating his position as the world’s Number One driver.

Gilles was a very special racing force. He was a brilliantly-gifted, abnormally determined, racing driver – a Nuvolari of his times – but he was also straightforward and uncomplicated, driven only by the desire to wield a good racing car better than the next man. He always used to say, in those impromptu coffee-shop dinners we used to have, when he would eat pasta alla panna, followed by vanilla ice-cream with hot chocolate sauce, that he would dream of the perfect race: “I win the pole, drop to last after getting a puncture on the fifth lap and then pass every car to win with half a minute to spare…” When someone pointed out that Alain Prost nearly did that in South Africa in 1982, Gilles replied, “Yes, but that doesn’t count. He did it in a superior car. My car would have to have less power than all the others…!”

At Long Beach, 1982, talking in the garage area about how bad this generation of F1 cars is to drive – even for a talent like Gilles – he said that he would dearly love to do a Formula Atlantic race again. “You know, get a good car, do some testing and then go and blow everyone away at Trois Rivieres or somewhere. And then after that I’d do a Can-Am race. Can-Am cars are fantastic. They look great, they have lots of power and they even have suspension. I tell you, the crowd would love it. So would I…”

I’ll miss the rides to the circuit with Gilles. In Brazil every year he would offer me a seat in his hire car (usually something as innocuous as a Fiat 127) and every year I would vow never to accept again. Two-lane roads became three-lane highways. Footpaths became run-off areas, cross-roads chicanes.

I shall miss, too, the man who was good enough – or respected enough – not to be afraid of conducting a standing, public argument with Bernard Ecclestone. There are plenty of people in racing prepared to talk about Ecclestone behind his back; Gilles was one of the few who would actually tell Ecclestone what he thought. Ecclestone did not leave South Africa, 1982, I believe, with a high regard for Villeneuve’s opinions but he did leave with a respect for a man who would say what he believed. In the same way, Gilles was proud of the way that he was not sponsored in his later years by the ubiquitous Marlboro brand. “Why should I be a member of the so-called ‘Marlboro World Championship Team?’” he said. “Half the grid are in it – so that’s a recent for being different. Besides, they wouldn’t be able to afford me…”

Gilles did things as he wanted to do them, never mind the establishment. He lived, during the European races, out of a motorhome, or camper, as he called it. That way he could avoid the hassle of hotels, could sleep-in before practice and could have a quiet retreat during the day. He didn’t have the camper at Zolder because, for once, his wife, Joanne, and his two children, Jacques and Melanie, were not at the race. It was to have been Melanie’s First Communion on race day and Joanne wanted to be there with her.

In recent weeks, Gilles had not been happy with his Formula One racing. He talked about leaving Ferrari at the end of the year – and, if Ferrari didn’t give him a release, of signing for another team and simply not driving for a year. He said he could do with the rest and would come back, fresh and eager. When he won South Africa in 1979 he drove to the hotel with a list of Grand Prix stats alongside him. “Let’s see,” he said. “Jackie Stewart has won 27 races. That means I’ve got 26 to go to break his record…” Right up until Zolder, Gilles believed he had the time – and of course the ability – to achieve that goal. Few disagreed with him.

Most of all, though, I shall miss seeing Gilles drive. So long as Gilles was practising, or was still in the race, there was always someone to watch, someone to laud. Sure, he was over the top sometimes. For every mistake, though, he would drive the next few laps sublimely.

In South Africa in 1982 we sat by the swimming pool of the Kyalami Ranch. It was a cool, clear night and the subject turned to his early days, to the old Skoda he used to drive and to his first races in Formula Ford. He told me something then that he told me to keep to myself – but that was only because he thought people would take it out of context, or think him big-headed. I repeat it now because Gillles never boasted, never put himself first. Instead, Gilles was probably the most sincere person I have ever met.

This is what he said, in confidence:

“You know, the first time I drove a single-seat car – the Formula Ford – I thought to myself, ‘Boy. If I never make it beyond Canada the world will miss seeing a very great driver. I know it. Just know it.’”

He was right. Drivers like James Hunt, Chris Amon and Patrick Tambay saw Gilles in Formula Atlantic or CanAm and came back to Europe speaking of a new Canadian star the like of which had been rarely seen. Gilles went on to win six Grands Prix, and the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, and to establish himself as the fastest, and the most adored, driver of his era. “He was the best guy in racing,” said Niki Lauda “- and he was unquestionably the quickest.”

When news of the accident reached the Zolder pits I ran over to the scene with my friend, Nigel Roebuck. Together, we shared our grief. I flew then to Berthierville, Quebec, for Gilles’ funeral. I had to change planes at JFK, missed my connection and spent a sad, lonely night in a sordid Holiday Inn. This was the F1 life at its lowest.

Soon after the accident, though, life at Zolder had quickly re-started. There were calls for qualifying to resume as soon as possible. There was a saloon car race to be run…

A driver wandered up to us, asking who we thought Ferrari would hire in place of Gilles. Nigel and I stared blankly back.

“I should think Ferrari’ll have a job coming up with a replacement,” he continued inanely.

“Yes,” said someone else. “And so will Formula One.”

The next photo on that strip of film is this shot I took of Gilles about to climb into Ferrari 126/CK2/057 for another test run. (The following week he would lead the race for 29 laps). I returned the wave!

Below: Monza, 1981: Gilles with Ferrari’s Team Manager, Marco Piccinini (left) and 126CK designer, Harvey Postlethwaite. Note the “Viva Cuoghi” graffiti on the wall: Ermanno Cuoghi was a classic Ferrari mechanic before Niki Lauda lured him to Alfa!

A disgruntled Gilles studies the qualifying times at Zandvoort, 1981, where the Ferrari was woefully uncompetitive. I took this shot in his “camper”, which he parked right next to the Ferrari trucks behind the pits, intensely annoying the power-brokers. Driven all over Europe by a lovely Canadian couple named Louise and Norman, the huge, articulate home-away-from home was always immaculate. Gilles didn’t have to ask us to remove our shoes as we stepped in; it was a natural reflex

A disgruntled Gilles studies the qualifying times at Zandvoort, 1981, where the Ferrari was woefully uncompetitive. I took this shot in his “camper”, which he parked right next to the Ferrari trucks behind the pits, intensely annoying the power-brokers. Driven all over Europe by a lovely Canadian couple named Louise and Norman, the huge, articulate home-away-from home was always immaculate. Gilles didn’t have to ask us to remove our shoes as we stepped in; it was a natural reflex

I don’t think Gilles knew too much about Carlos Reutemann prior to joining the Ferrari team in late 1977. As time passed, though, and as Carlos showed his class, Gilles began to respect him more and more. I had a long chat with Gilles in South Africa, 1978, the gist of which was, “Wow! I didn’t realize Carlos was that quick. I’m learning a lot from him. A lot…” I was also pretty close to Carlos at that point, so Gilles and I used to have a lot of laughs about Carlos’s idiosycrasies (of which there were many!). When Carlos won at Watkins Glen that year (and Gilles retired with a blown piston) he started a new thing, as in “Bloody Peter – for sure you and Carlos screwed my engine…” He didn’t always call me “Bloody Peter” after that – but he liked to joke about it when the mood was upon him. When I asked him to sign an excellent Chuck Queener print at The Glen in 1979 he therefore lost no time in reminding me about the events of a year before! That day in ’79, of course, Gilles was supreme in the drizzle, reminding everyone of how he could so easily have won the Championship that year instead of Jody. Indeed, Carlos spoke to Gilles before the 1979 Italian GP clincher and said, basically, “Don’t fool around with the Championship, Gilles. Don’t give it away. If you have a chance, take it. Championships are very hard to win. You may not get another chance.” Gilles replied, “Nah. I’ve promised Jody I’ll let him win. He’s going to help me win it in 1980…”

The legend begins….

In October, 1978, in the cold of the Canadian fall, Montreal staged its first Grand Prix. The race also enabled a young driver from nearby Berthierville to win his first Grand Prix. And so the legend of Gilles Villeneuve was born. We join that momentous week in the newly-completed Hyatt hotel, headquarters of the Labbat’s Grand Prix of Canada

Wednesday, October 4

The Hotel Hyatt Regency is a $50m tower in the south of downtown Montreal. It is one year old; it is in keeping with the newness of this part of the city. It is also serving as “Grand Prix Headquarters”, which means that you collect your credential from the basement of the Hyatt, that the pre-race festivities, like the Gilles Villeneuve Ball, are held at the Hyatt, and that most of the Grand Prix teams, including mechanics, stay at the Hyatt. Some remain aloof – Walter Wolf’s team for one, Michelin for another – but, otherwise, this is already a Grand Prix with a difference: the paddock area is effectively marble-floored and graced with Muzak.

This morning, with most of the teams together again after two or three days in New York, or brief trips to the Goodyear factory in Akron, Ohio, is to be much like any other. Emerson Fittipaldi is clad in a red-and-white track suit as he sits down to breakfast, and Jody Scheckter is wearing his white outfit from TV’s “Superstars”. Emerson will later train at the nearby, indoor athletic track; Jody will hit a tennis ball or two. Everything is within easy reach, within calling. Clay Regazzoni, with “Klippan seat belts” emblazoned on his track suit, has booked a court for two hours. Patrick Tambay will play with John Watson, Jacques Laffite and Riccardo Patrese. Lauda and Hunt? They are to stay at the hotel today, recovering from what must best be described as a quick trip to New York. The weather was better down there – but that would appear to be all. Here, in Montreal, only two miles from the circuit, there are facilities to make out-of-town Grands Prix look positively ancient. The shopping malls are so large you need a golf cart to cover them.

This, then, is a glimpse of the future: the more the Grand Prix business expands, the more inclined will be the business to stage its races near or in major cities. Who wants to camp at Mosport when you can be in the Hyatt ten minutes after practice? At Montreal, you do your next Goodyear deal in the air-conditioned bar, 30 minutes before dinner (and not in sokme steamed-up, hired motorhome). Is there a downside to it all? Will the Montreal “street” circuit justify the Hyatt? We shall see on Friday, when practice begins.

There is an end-of-year feeling in the Hyatt this winter’s morning. The Championship has been won; for drivers like Niki Lauda the race is of only academic interest, even if this is his – and also Carlos Reutemann’s 100th GP start – even if second place in the title chase is still wide open. For drivers like Jean-Pierre Jarier, Keijo Rosberg and Rene Arnoux, by contrast, there is everything – including a good drive for 1979 – for which to fight. And for teams like Ligier this is the time to say goodbye to the Matra engine. Indeed, this is the over-riding, pre-practice mood: such has been the dominance of the Lotus 79 that a good number of cars will be having their last race at Montreal: next year they’ll all be going ground-effect.

That’s your first glimpse of this first Canadian GP in Montreal: it is at once a glimpse of the future and a last look at the past.

Thursday, October 5

You reach the track by turning left out of the Hyatt, driving 500 yards on the freeway and taking the “Ile Note Dame” ramp. Over a bridge, onto the island – and you are there, at the sight of Expo 67 and the 1976 Water Olympics.

The island is small – artificially built out of earth moved when the city’s underground railway was constructed. And, necessarily, the circuit seems small. It stretches the length of the island, with hairpins at either end and six chicanes in between. It is also brand new: the timber is still light-coloured, the grass verges recently-placed, the paint still tacky. Everywhere, artificiality prevails.

The cars are garaged in the old rowing sheds, back-to-back and side-by-side, as at Monza. And the pits are a short walk away at the exit of the hairpin, before a quick chicane.

We are out on the course now, tooling around in a road car, when up comes Hans Stuck Jnr, completely sideways in his Mercury Monarch. A grin splits his face: it must be Hans’ sort of circuit. Then Mario Andretti passes us, his station wagon on opposite lock out of the hairpin, avid journalists round about him. (And ready to cause him some bother, it turns out: remarking the circuit seems a little tighter, and a little slower than it might have been, and concluding lightly that the track seems designed for Gilles Villeneuve, he subsequently is quoted out of context by the local press. Mario is impressed with the organizers and with the circuit build overall, but the locals whack him hard re his Villeneuve comments. By Sunday morning he is saying to the media: “My criticism was over-emphasised and mis-directed. I am not critical of the race organizers. I am more critical of our own FOCA officials who were sent over here to approve the track”.)

Gilles in the wet on Friday, when his team-mate, Carlos Reutemann, had the advantage

Friday, October 6 Read more…

Some classic Gilles

As we approach the 30th anniversary of the passing of Gilles Villeneuve, let’s look back at one of his most famous wins – the 1981 Spanish GP at Jarama. Against all odds, Gilles withstood race-long pressure to beat his four pursuers by 0.2sec.

All pictures courtesy of Sutton Images (the David Phipps Archives)

“I’M REALLY upset,” said the Monaco winner, Gilles Villeneuve, walking into his personal motorhome. For once, he didn’t remove his shoes. On this opening practice day at Jarama, near Madrid’s international airport, even the cleanliness of his wall-to-wall carpet took second place to the handling of his Ferrari 126CK V6 turbo. “I mean, I win Monaco, score nine points at a circuit that didn’t really suit us, and then we come to Jarama, where the car should be quick. And this is my reward: terrible handling. Shocking. I’m not flat on any of the four quick corners. The car is a disaster. Maybe for two or three laps, when the tyres are new, it’s not bad on the tight stuff. But after that it’s impossible. Worse than last year’s T4. Much worse. Oh, we can work at it. We can make the car driveable, I guess, for the race. But we won’t stand any chance of winning – not when we’re this bad. You’ve only got to look at the lap times. We’re two seconds off the pace. If you assume that our engine is worth half a second over the Cosworths, which it is, that puts us two-and-a-half seconds away. It’s ridiculous.”

That was Friday. On Saturday, Gilles squeezed the absolute maximum out of his standard-wheelbase 126CK and, on a brand new set of Michelins, lapped in 1min 14.9sec. That would have made him fifth quickest on Friday and it made him seventh fastest overall. He still wasn’t flat on the quick corners but he was spectacular. So quiet is the Ferrari engine that you could hear his rear tyres skipping over the kerbs while he kept his foot on it with his arms fully-crossed. “It’s quite funny,” he said afterwards. “On the quick corners you can see the track marshals running for cover…”

For the second consecutive race, Gilles made a perfect start. He could see Laffite edging forward and then stopping, edging then stopping, just as the pole man often does. Gilles went when the centre of the red light began its first millisecond of fade, weaved around Lafitte, banged wheels with Alain Prost – and found himself third, behind the two Williams, as they braked for the first (double-apex) right-hander. Over the lap he followed Reutemann (or “bloody Carlos”, as he affectionately calls his ex-Ferrari team-mate). The Ferrari felt reasonably good on full tanks, so Gilles darted right as they left the right-hander at the end of the lap. The power of the Ferrari took him easily past the Williams. Second place was his. After the South American races, when Gilles had had trouble with a broken drive-shaft, Enzo Ferrari had addressed his engineers tersely: “I don’t ever want to have a Ferrari retire for that reason again.” For Monaco, sure enough, Ferrari had fitted their biggest possible drive-shafts and Gilles had been able to bounce them off the guardrails and hit kerbs and apply full power down over the bumps without the slightest hint of trouble. On the Monday after that race, he had sent a Telex to the Commendatore, explaining a lot of things that had happened over the weekend. He finished it thus: “For 76 laps I tried to break your drive-shafts but I wasn’t successful. Thank you very much.” Knowing that the Ferrari was that strong, that he could do virtually what he liked with it, Gilles reeled off his laps at Jarama. For ten laps he saw a plus-sign over Carlos (never more than two seconds) and a minus-sign to Alan Jones. This grew larger by the lap, and was up to ten seconds by lap 13. On the following lap, though, Gilles had an unbelievable slice of luck: he accelerated out of the uphill hairpin and glimpsed yellow flags, waved frantically. He braked early for the next right-hander – and saw Jones’s Williams, sitting stationary in the sand. Head down, he completed his 15th lap in the lead of the Spanish Grand Prix.

On the 79th lap, with one to go, they were still behind him. Read more…

Catching up with Sir Stirling

On the eve of the 2012 season, in the historic London Hilton, I caught up with one of the greatest of them all – Sir Stirling Moss. (Part One of a two-part interview originally recorded for http://Speed.com.)

Mario Andretti on TFL

It was an absolute joy to chat to Mario Andretti on Wednesday’s edition of The Flying Lap (see link above) – and, for me, one of the best moments came when Mario was describing his return to Ferrari (at Monza, 1982). We used this beautiful Sutton Image during the show but I wanted to reprint it here because it certainly deserves closer analysis. It’s taken at the entry to the Parabolica, of course, but what I particularly love about the pose here is the absolute neutrality of Ferrari 126CK2/061 – something that Mario was able to reproduce almost to perfection when his car was right and he could “feel” the surface of the road. There’s a certain slip angle at the rear but Mario’s subtle use of steering against a decreasing brake pedal pressure has given him exactly the poise he needs mid-corner. There’s no doubt that Mario used lower minimum corner speeds than, say, Ronnie Peterson (at John Player Team Lotus) or Patrick Tambay (at Ferrari) but for sure he was able to make up for that – and give himself an edge – with his exits. Earlier in the interview, I was also fascinated to hear Mario talk about how much he learned about driving from Bruce McLaren. We perhaps tend to think of Bruce these days as one of the ultimate driver-engineers and forget that he was, too, a first-rate racing driver. It was in slow-corner rotation (an area often taken too much for granted by drivers blessed with great car control) that Mario told us Bruce had been particularly instructive. In the picture above (taken, I believe, by the great Nigel Snowdon) note, too, that Mario is leaning his Bell helmet slightly to the left. Peter Revson also used to do this (on both left- and right-handers): I think it is a characteristic of drivers who have seen plenty of banked corners (ie US ovals) in their time.