I spoke recently to the FIA’s F1 Race Director, Charlie Whiting. What does he think about the new engine regs for 2014? And what, indeed, does he think about the F1 life?

I find Charlie Whiting in his second home – in the office at any given Race Control building in any given F1 track of the world that bears the title, “Race Director”. We happen, on this occasion, to be in Austin, Texas, where the new Hermann Tilke-finished Circuit of Americas is undergoing its baptism by fire. And this is about the only time of the weekend when Charlie has a moment or two in which to chat. It is the lull after qualifying on Saturday. The F1 cars are in Parc Ferme conditions (under wraps in the team garages). And, baring the odd technical political or technical crisis or two (or three), Charlie can relax just a little, exhale some air and think about…the racing life.

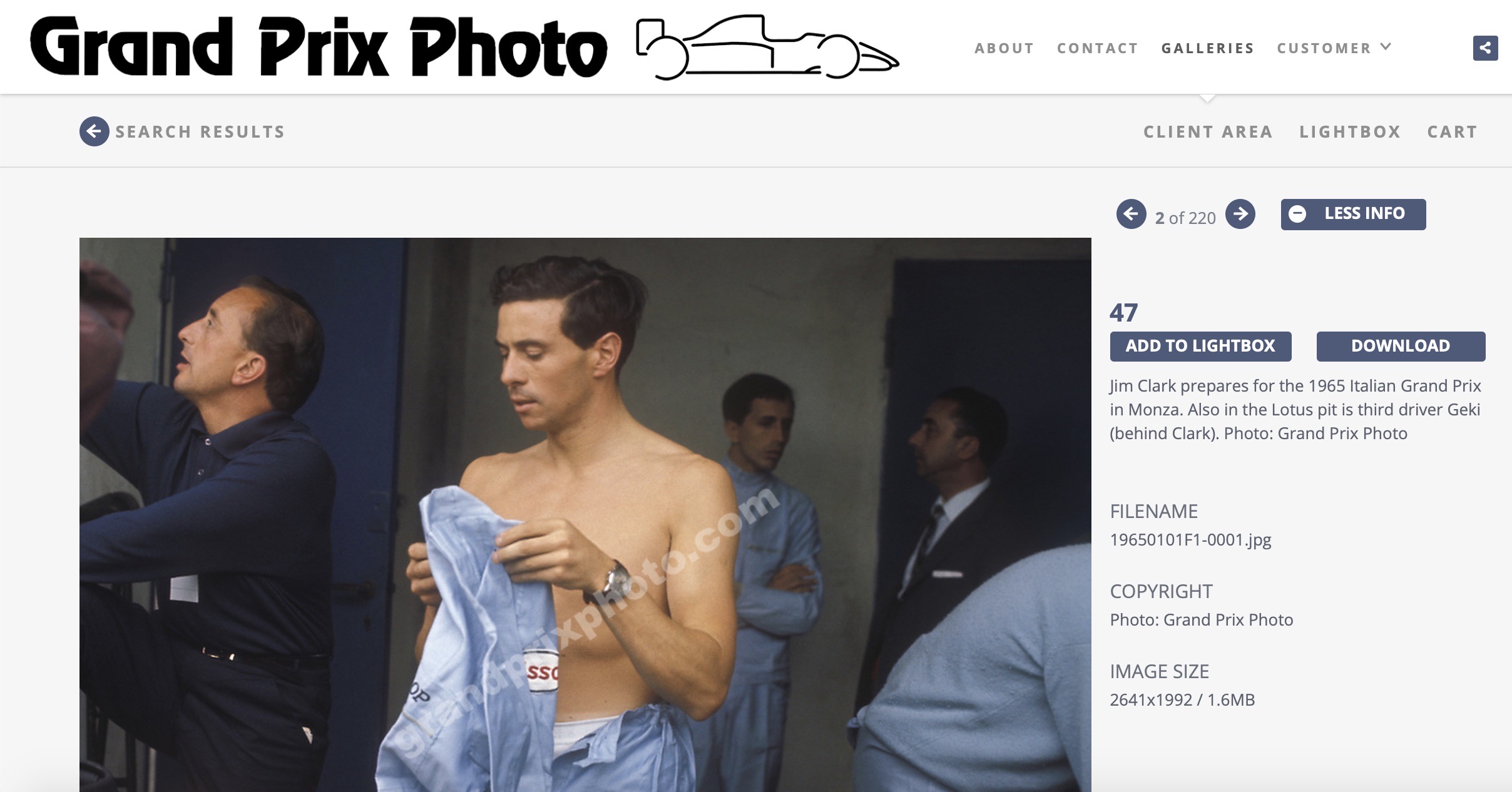

“You’ve been in motor racing for quite a long time,” I say to the man whose silver hair speaks of 40-or-so years in the business but whose body is still that of the ever-young F1 professional. He wears a neatly-pressed light blue, short-sleeved FIA shirt against dark blue slacks. And his room for the week, as ever, is Spartan. A desk, a table with a couple of chairs. A laptop (fed by just-for-the-weekend 100-plus mgb speeds). The inevitable briefcase. No family snaps in leather frames. No mascots.

“Yes,” says Charlie. “Since the age of 14, actually. I’m 60 now, so that’s 46 years. Long enough! And everything still seems like yesterday. I can still recall Lydden Hill rallycrosses in vivid colour. But then, when you think about it, it was a long time ago. The thing that brought that home for me recently was that it’s now been 30 years since I was Chief Mechanic to Nelson Piquet at Brabham when we won the World Championship (in 1981 and 83)…”

I wonder, often, when I see ex F1 Brabham team people like Charlie or Mike “Herbie” Blash, or Alan Woollard or Eddie Baker or Nigel de Strayter, all of whom today work either for the FIA or FOM – I often wonder if they do spend any time thinking about the past. It’s F1 folklore that the only day that matters is tomorrow, that nostalgia is for the weak – and always I imagine that that’s even more the case when you work for the FIA or FOM, where so much of the emphasis is on politics, money, the future, the F1 show. Prod them a little, though, and away they go…

“I joined Brabham at the tail end of the BT45 and the BT46-Alfa, when Niki Lauda and John Watson were driving for us. They were lovely cars. Lovely. When you think how simple they were – they didn’t seem simple at the time – but they are very, very simple cars by today’s comparison. The complication was in the detail. On the BT45 you had to take the engine out to change the spark plugs! As a mechanic, that seemed complicated to me….”

Continuing the theme of finding the racer behind the top-line FIA official, I ask Charlie about his early years. How did it all start?

“Through my brother, Nick” (who was a successful saloon car racer in the 1970s). “We did a deal with John Webb at Brands Hatch, who was trying to help Divina Galica into motor racing in 1976. With Shell sponsorship, we – Nick and I – acquired a Surtees TS16. I prepared it and Divina drove it in the Aurora Championship. We bought a TS19 for the following year, and then Divina took Olympus sponsorship into F1 with Hesketh in 1978. I went with her, and worked for Hesketh, but things didn’t go particularly well that year unfortunately and it all ended after the Belgian GP. I then got a job at Brabham through Herbie – on the test team with the BT46-Alfa, which was a lovely car, as I say. I did one test and then for some reason I was on the race team for the French GP. I stayed there. Nelson Piquet came along in 1979 and made the team his own, really. It was an amazing time.

“And I guess,” I add, remembering the slickness of the Brabham team back then, and the almost surgical precision of its operation, that at that point you would have been thinking, ‘This is a great job. Brabham Chief Mechanic. The future’s secure…’ You wouldn’t have been thinking beyond that?”

“Of course not,” agrees Charlie. “You don’t look that far ahead. I’ve always had ambitions and when I was working as Nick’s mechanic in the early 1970s, building Escorts, I always wanted to be an F1 mechanic. My ultimate goal was to be a mechanic to an F1 champion. That, so far as I was concerned, was the greatest thing I could aspire to. I did that twice and I was rather pleased with myself about that, I must admit.”

I’ve know quite a few F1 mechanics who speak of a sense of anti-climax when they finally win a championship. Some don’t even receive a handshake from the driver, let alone a pay rise. For Charlie it was different:

“I loved every minute of it. Amazing feeling. Being in charge of a team when you win a Grand Prix was just a fantastic feeling and I would never tire of that.”

1981 was an interesting year, of course. Carlos Reutemann lost the Championship by one point but was stripped of a nine-point win (scored in the opening round in South Africa) a couple of months into the year when it was decided (for “political” reasons) to strip the race of its championship status. Then there was the mysterious, larger rear wing fitted to Nelson Piquet’s Brabham after qualifying at Monaco (but before the weight check!) and the brilliantly-conceived, valve-operated Brabham ride height control system. In a nutshell, the system was fully legal and enabled Brabham to dominate the early rounds of the season (give or take a wrong tyre choice in Brazil). For Zolder, though, the FIA legalised a much more basic lever-adjustment system that brought all the other F1 teams back into contention. One imagines that such about-faces – and creativity – merely added to the graduate education of Charles Whiting.

“Monaco 81? Qualifying?” asks Charlie with a smile. “I’m not sure what you mean… Now the ride height – that was something. It was a fiendishly clever system that was 100 per cent legal and which no-one could understand. I remember Gerard Ducarouge” (the Ligier designer) “trying to wriggle his way down the cockpit to find the lever that moved it up and down. There was nothing there! It was all valve-operated, orifice-controlled. The problem is that the suspension took a long time to come back up. It was also a bit complicated, with lots of pipes and things that could have fallen off.

“In the first race in Argentina we were amazingly quick. Hector Rebaque, our second driver, went right round the outside of Alan Jones on that long corner out the back. It was just awesome to watch. Unfortunately he didn’t finish, though, and retired right by the pits, with the suspension still down. Everyone clocked that and so obviously with Nelson’s car, which was winning easily, we were on tenterhooks to see if it would come back up again…”

Charlie didn’t elaborate here, but (in a nice counterpoint to what would occur in Singapore 27 years later) legend has it that Nelson had selected the exact rail of Armco barrier against which he was going to crunch the Brabham on its slow-down, victory lap in the event that its suspension was still down. Thanks to Nelson’s judicious use of kerbs, the ride height was legally up by the time he reached the potential accident zone, although Nelson couldn’t resist winding up the Brabham boys who were watching a hazy black-and-white TV monitor on the pit wall. Pretending to steer towards the relevant Armco and then veering away at the last second, he gave them all a cheeky wave as he drove on to the podium and thus to scrutineering. The gesture was lost on everyone else…

“We had an amazing team, the best of its day,” says Charlie wistfully. “Obviously Colin” (Chapman) “was brilliant in his own way, but Gordon Murray came up with some great ideas and Dave North, too, was a very clever guy and probably still is, as far as I know.” (David is with LotusF1.)

Which segways us neatly back to 2012. I ask Charlie about the quality of talent in the F1 pit lane – about whom he most respects.

“There is a mutual respect within the paddock. I don’t think there’s anyone out there I respect more or less than any of the others. You have to earn respect, don’t you? There are some exceedingly clever people out there but I think they know me well enough by now not to try to pull the wool over my eyes. There’s a certain amount of respect there not to do those sorts of things. When someone does it it’s so obvious…so they don’t try. It takes a long time to reach that situation. The thing is, the F1 pit lane is full of brilliant people, of people who think very quickly on their feet. The standards in F1 are very high.”

What is the most enjoyable part of his weekend?

“I love it all so much that it’s difficult to say but I think the biggest adrenalin rush is the start. You never tire of that. You still get nervous and it’s still high-tension. Lots of things can go wrong but the best thing about my job really is the lack of routine. Every day is different. Literally, you never know what might happen. You never know what’s around the corner. You never tire of that.”

And what about the new F1 technical regulations for 2014? What does he feel about the new turbo V6 engines (and the talk about how the show will be diminished by the loss of high-revving, normally-aspirated screaming sound.)

“It’s a big challenge,” says Charlie. “A very big challenge for the engine manufacturers. I’m looking forward to seeing the engines run – to see how complicated they are and how clever they are. They’re going to be extremely high-tech power units, that’s for sure. As for the sound, I think people will get used to it pretty quickly. Honestly, when I think back to the old BMW four cylinder engine we ran in the Brabham days, that revved to 11,000rpm and it sounded fine. The new engines are not going to be silent. The sound is going to be different but people will get used to it very quickly, I think.”

I also ask Charlie about his thoughts on the new-look Silverstone:

“Living very closely to Brands Hatch when I was growing up, I only went to Silverstone three or four times until I became involved in F1. Today, they’ve done an enormous amount of very good work at Silverstone. The track is now one of the nicest we’ve got. It’s not like a really modern circuit, where we have asphalt run-offs and all the latest gadgets, so it’s still got a good feel about it. It’s a proper racing circuit. Obviously they’ve had to make improvements to bring safety up to a required standard but they’ve still got that standard of a real race track, I think. And there are fewer and fewer of those on the calendar.

There’s another knock on the door. Charlie is wanted. I ask, quickly, about his life right now – and about the future (bearing in mind that I believe his contract with the FIA is up for renewal at the end of 2013.)

“I’m looking forward to the time when I do a little less of this and bit more of that,” he muses. “I live at present in a very complicated way. It’s a very busy year, requiring me to be on the road about 200 days out of 365. I’ve got a wife and two young children, and of course it’s very hard to be away from them. We live in Monaco and we spend time in the UK as well and with schools and things like that it’s hard to juggle everything and to be there as much as I can. Aside from the F1 races 20 times a year, I’ve got lot of circuit inspections to do, the Technical Working Group, the Sporting Working Group, the Circuits Commission, the Research Group, the Safety Commission, the Single-Seater Working Group – all these groups require one meeting after another…”

I wonder, too, at Charlie’s fitness and general energy.

“I barely have time to go the gym. I walk a lot and I suppose I try to walk as quickly as possible. That’s my main form of exercise.”

Walks aside, you suspect, it’s that 100 per cent, start-line adrenalin that so successfully has made, and makes, Charlie Whiting the FIA’s F1 Race Director: he’s a Racer out there marshalling the Racers, second-guessing them, applying his years of ups and downs and not a little native cunning to prepare yet again for maybe what they’re going to think of next.

In Austin recently, Charlie (right) shares a joke with former (US) F1 privateer, Brett Lunger