Gilles – in the mould of Nuvolari

We enjoyed his supreme, audacious talent for only a few, dazzling years. And then the shining light was gone, extinguished by a stupid rule that obliged drivers like Gilles to take additional risks…as if there weren’t enough already. Thirty years on, here are a few of the photos I took of my friend – and some notes I made in May, 1982.

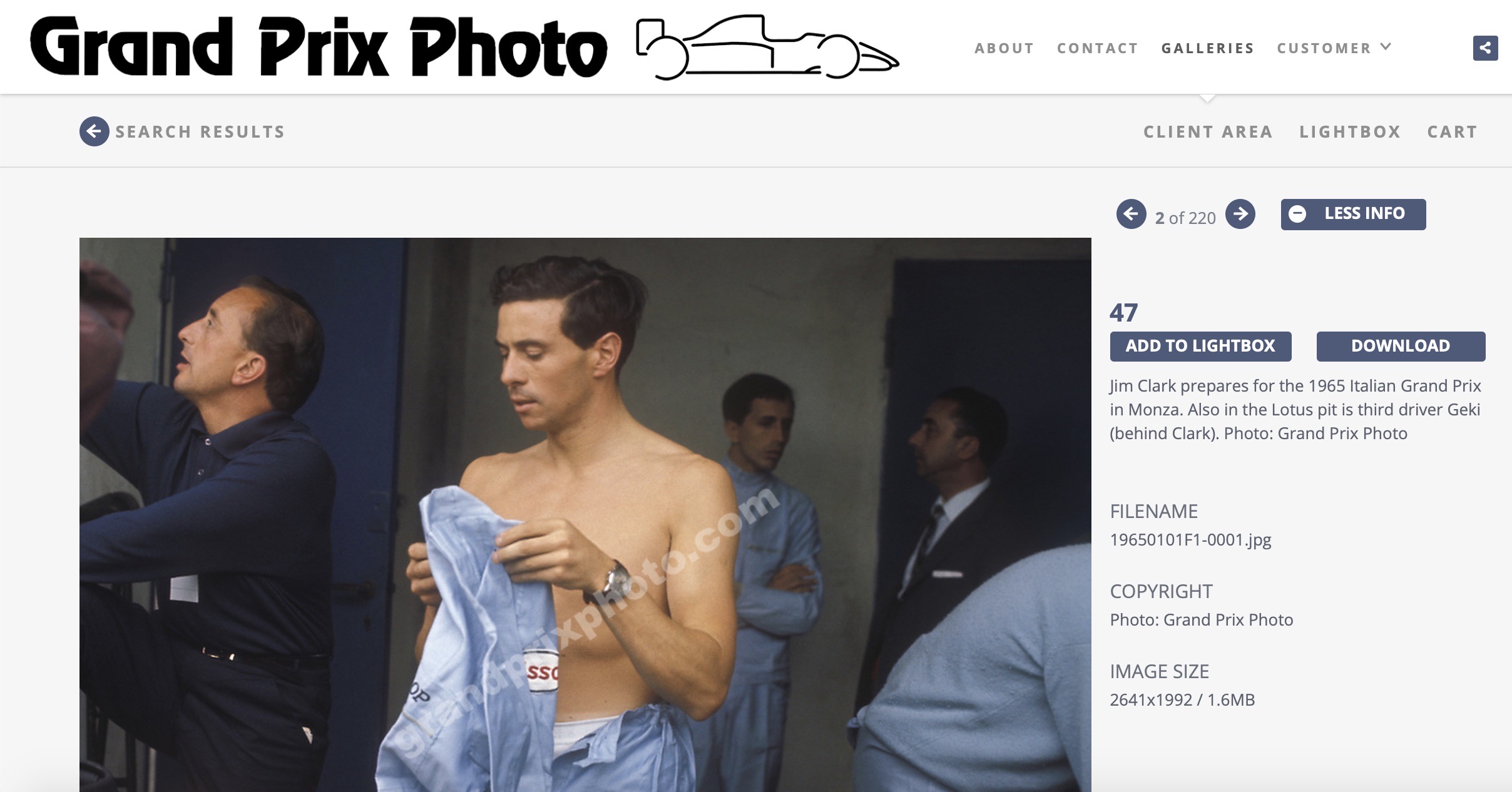

Brazil, 1982: spying a camera around my neck, Gilles grabbed it and snapped this self-portrait

I was standing by the phone booth in the Zolder paddock on Friday afternoon when I saw Gilles, lost in a big, yellow Ferrari transport van, sitting up there in the passenger’s seat. I waved. He beckoned the driver to stop and wound down the window.

“Which hotel are you in?”, he asked.

“The Mardaga,” I replied. “Quite close to the track.”

“Ok. Don’t worry. I thought you might like a lift to the Post House. I’ve got the new Augusta here. You haven’t had a ride in it yet, have you?”

I hadn’t, although my next project was certainly to fly to a race with Gilles. It was his idea. He wanted everyone to enjoy his new baby.

With that, Gilles drove away. I never spoke to him again. The next day, he fell victim of exactly the sort of racing accident he had been forecasting. He was on a flying lap; there were ten minutes of qualifying remaining; and he was on his third (“mixed”), last, set of qualifying tyres. Didier Pironi, his “team-mate”, had annoyingly just bettered Gilles’ time by 0.1sec. In total, 30 cars were running. What with the qualifying tyre situation, and the lightweight Cosworth cars, there were more guys out there, cruising the lap, than there were cars going quickly. The day before, Gilles had been irritated yet again by the traffic problem. “It’s no worse that usual, I guess – which means it’s very bad. Every time I was on a quick lap I came across someone going slowly. Like I’ve said a million times before, it’s crazy being allowed only two sets of tyres. You’re forced to take ridiculous risks.”

In one such incident that Friday, Villeneuve had to brake hard to avoid running into the back of Jochen Mass’s March. Indeed, the Ferrari incident report from that day, in a tragically prophetic statement, said: “The French Canadian expressed himself absolutely amazed at the ‘early braking’ habits of some of the slower drivers, and confessed to having a couple of nasty moments when he nearly collected a Renault and a March…”

So it was the following afternoon. Villeneuve, on the limit and heading for a quick time, crested the rise after the first chicane to find Jochen Mass’s March ahead of him. Jochen says he was going slowly – in fifth gear, but certainly not flat through the left-hand kink and the short straight that follows it. “I saw Gilles in my mirrors,” he said later, “and expected him to pass on the left. I moved right and couldn’t believe it when I saw him virtually on top of me. He clipped my right rear tyre, bounced off the front and was launched into the air…”

Mass went on to say that he could imagine how Gilles had reacted. He was on the limit, there was a slow car ahead of him, he didn’t want to back off and he had to make an instant decision – left or right? “I have been in a similar situation at that place before,” said Mass. “It’s difficult, because although it’s a left-hand kink it’s possible to get by on the outside. He obviously chose to go on the outside and there wasn’t room.”

From Gilles point of view, of course, it would have been much less decisive. He would have seen Mass in the middle of the road – would probably have thought about Friday for a millisecond – and then he would have had to have made an instant call about which side Mass was going to move. With a left-hand kink approaching, he obviously thought Mass was going to move over to the inside. Thus Gilles went to the right. Thus the impact.

Travelling as slowly as he was – particularly in the closing minutes of qualifying – Mass in my view should have been either on one edge of the road or the other and making it very clear on which side he wanted to be passed. Critics of Villeneuve say that he had the option to back off if he was unsure; as Gilles said so many times, however, the pressure of running only two sets of qualifiers behoved the drivers to take risks and to gamble. And on Gilles the pressure was even greater: he was virtually a lone crusader against the danger of running only two sets of qualifiers. All the other drivers, wary of stirring the waters, remained more or less quiet.

The impact, when the 126C hit the ground, was catastrophic. The seat belts pulled out of the rear bulkhead of Harvey Postlethwaite’s carbon-aluminium chassis and Gilles, still in his seat and holding the steering wheel, was thrown onto the side of the track through two layers of catch fencing. Gilles’ GPA helmet – fastened around its based by a “hinge” system – came off and rolled to a halt a few feet away. From the point of impact with Mass’s March, the Ferrari had flown and crashed through a debris field about 150m long.

Mass stopped. So did Didier Pironi. Mass led Pironi away. And then, ten minutes later, Gilles was flown by helicopter – not his own – to a nearby hospital. He was gravely injured, unconscious but showing vital signs.

He had no chance, though. He passed away shortly after 9 o’clock that night.

So it was over. Just like that. A stupid accident caused by hitting a slower car – although the real cause, as Mass pointed out, was the lunacy of having to use only two new sets of qualifiers. Eddie Cheever would talk endlessly about how close Gilles came to hitting him at Rio. And, in South Africa, during the drivers’ strike, increasing the number of qualifying tyres was Gilles’ Number One topic of conversation. The other drivers soon tired of it all.

Just as we had to await Niki Lauda’s accident to see how right he was about the Nurburgring, so it was left to Gilles, in the saddest of ways, to demonstrate the point about qualifiers. Too late, the future would have much to say about the tyre rules. Racing, meanwhile, lost its heart and its soul.

There was no question that Gilles was on edge during practice at Zolder. The comments he made about Pironi after Imola showed no signs of mellowing. He was incensed even more by the people who had since declared Imola “a great race”! “That wasn’t racing,” he said with disgust on Friday at Zolder. “Every time I backed off Pironi passed me. Then I had to fight back to take the lead. I don’t call that a race…”

Gilles walked around the Zolder paddock quickly, pointedly. The days of laid-back Gilles were over. From everything he did, from jumping from the back of the new pits complex to the roof of the Ferrari transporter, or sitting impassively in his 126C, arms folded, while mechanics prepared the car for his final, flat-out run, you got the impression that Gilles was saying, “Right. The playing is over. From now on I take no prisoners.”

And so Gilles, in those last few days of his life, engendered the one thing he had always lacked – ruthlessness. Before Imola he was full of praise for his “team-mate”. He even came to Pironi’s defence when Joanne pointed out that it was quite rude of Pironi not to have invited Gilles to his wedding. “He probably just forgot,” said Gilles, ever the noble soul. In 1978 Gilles had been humble enough to say that he was “delighted” to be Number Two to Carlos Reutemann at Ferrari. Ditto in 1979, when he agreed before the Italian GP to let Jody Scheckter win the Championship, even though he, Gilles, was still right in the title race with a serious chance. “Don’t worry, Jody. You can help me win it next year,” he said. The next year, though – 1980 – the Ferrari turned out to be a dog. A lazy dog. Of course Gilles believed that he was quicker than Pironi but never, prior to Imola, would he concede that Pironi was any sort of threat – political or otherwise.

After Imola, that changed. Tougher than ever, Gilles was in the process of consolidating his position as the world’s Number One driver.

Gilles was a very special racing force. He was a brilliantly-gifted, abnormally determined, racing driver – a Nuvolari of his times – but he was also straightforward and uncomplicated, driven only by the desire to wield a good racing car better than the next man. He always used to say, in those impromptu coffee-shop dinners we used to have, when he would eat pasta alla panna, followed by vanilla ice-cream with hot chocolate sauce, that he would dream of the perfect race: “I win the pole, drop to last after getting a puncture on the fifth lap and then pass every car to win with half a minute to spare…” When someone pointed out that Alain Prost nearly did that in South Africa in 1982, Gilles replied, “Yes, but that doesn’t count. He did it in a superior car. My car would have to have less power than all the others…!”

At Long Beach, 1982, talking in the garage area about how bad this generation of F1 cars is to drive – even for a talent like Gilles – he said that he would dearly love to do a Formula Atlantic race again. “You know, get a good car, do some testing and then go and blow everyone away at Trois Rivieres or somewhere. And then after that I’d do a Can-Am race. Can-Am cars are fantastic. They look great, they have lots of power and they even have suspension. I tell you, the crowd would love it. So would I…”

I’ll miss the rides to the circuit with Gilles. In Brazil every year he would offer me a seat in his hire car (usually something as innocuous as a Fiat 127) and every year I would vow never to accept again. Two-lane roads became three-lane highways. Footpaths became run-off areas, cross-roads chicanes.

I shall miss, too, the man who was good enough – or respected enough – not to be afraid of conducting a standing, public argument with Bernard Ecclestone. There are plenty of people in racing prepared to talk about Ecclestone behind his back; Gilles was one of the few who would actually tell Ecclestone what he thought. Ecclestone did not leave South Africa, 1982, I believe, with a high regard for Villeneuve’s opinions but he did leave with a respect for a man who would say what he believed. In the same way, Gilles was proud of the way that he was not sponsored in his later years by the ubiquitous Marlboro brand. “Why should I be a member of the so-called ‘Marlboro World Championship Team?’” he said. “Half the grid are in it – so that’s a recent for being different. Besides, they wouldn’t be able to afford me…”

Gilles did things as he wanted to do them, never mind the establishment. He lived, during the European races, out of a motorhome, or camper, as he called it. That way he could avoid the hassle of hotels, could sleep-in before practice and could have a quiet retreat during the day. He didn’t have the camper at Zolder because, for once, his wife, Joanne, and his two children, Jacques and Melanie, were not at the race. It was to have been Melanie’s First Communion on race day and Joanne wanted to be there with her.

In recent weeks, Gilles had not been happy with his Formula One racing. He talked about leaving Ferrari at the end of the year – and, if Ferrari didn’t give him a release, of signing for another team and simply not driving for a year. He said he could do with the rest and would come back, fresh and eager. When he won South Africa in 1979 he drove to the hotel with a list of Grand Prix stats alongside him. “Let’s see,” he said. “Jackie Stewart has won 27 races. That means I’ve got 26 to go to break his record…” Right up until Zolder, Gilles believed he had the time – and of course the ability – to achieve that goal. Few disagreed with him.

Most of all, though, I shall miss seeing Gilles drive. So long as Gilles was practising, or was still in the race, there was always someone to watch, someone to laud. Sure, he was over the top sometimes. For every mistake, though, he would drive the next few laps sublimely.

In South Africa in 1982 we sat by the swimming pool of the Kyalami Ranch. It was a cool, clear night and the subject turned to his early days, to the old Skoda he used to drive and to his first races in Formula Ford. He told me something then that he told me to keep to myself – but that was only because he thought people would take it out of context, or think him big-headed. I repeat it now because Gillles never boasted, never put himself first. Instead, Gilles was probably the most sincere person I have ever met.

This is what he said, in confidence:

“You know, the first time I drove a single-seat car – the Formula Ford – I thought to myself, ‘Boy. If I never make it beyond Canada the world will miss seeing a very great driver. I know it. Just know it.’”

He was right. Drivers like James Hunt, Chris Amon and Patrick Tambay saw Gilles in Formula Atlantic or CanAm and came back to Europe speaking of a new Canadian star the like of which had been rarely seen. Gilles went on to win six Grands Prix, and the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, and to establish himself as the fastest, and the most adored, driver of his era. “He was the best guy in racing,” said Niki Lauda “- and he was unquestionably the quickest.”

When news of the accident reached the Zolder pits I ran over to the scene with my friend, Nigel Roebuck. Together, we shared our grief. I flew then to Berthierville, Quebec, for Gilles’ funeral. I had to change planes at JFK, missed my connection and spent a sad, lonely night in a sordid Holiday Inn. This was the F1 life at its lowest.

Soon after the accident, though, life at Zolder had quickly re-started. There were calls for qualifying to resume as soon as possible. There was a saloon car race to be run…

A driver wandered up to us, asking who we thought Ferrari would hire in place of Gilles. Nigel and I stared blankly back.

“I should think Ferrari’ll have a job coming up with a replacement,” he continued inanely.

“Yes,” said someone else. “And so will Formula One.”

The next photo on that strip of film is this shot I took of Gilles about to climb into Ferrari 126/CK2/057 for another test run. (The following week he would lead the race for 29 laps). I returned the wave!

Below: Monza, 1981: Gilles with Ferrari’s Team Manager, Marco Piccinini (left) and 126CK designer, Harvey Postlethwaite. Note the “Viva Cuoghi” graffiti on the wall: Ermanno Cuoghi was a classic Ferrari mechanic before Niki Lauda lured him to Alfa!

A disgruntled Gilles studies the qualifying times at Zandvoort, 1981, where the Ferrari was woefully uncompetitive. I took this shot in his “camper”, which he parked right next to the Ferrari trucks behind the pits, intensely annoying the power-brokers. Driven all over Europe by a lovely Canadian couple named Louise and Norman, the huge, articulate home-away-from home was always immaculate. Gilles didn’t have to ask us to remove our shoes as we stepped in; it was a natural reflex

A disgruntled Gilles studies the qualifying times at Zandvoort, 1981, where the Ferrari was woefully uncompetitive. I took this shot in his “camper”, which he parked right next to the Ferrari trucks behind the pits, intensely annoying the power-brokers. Driven all over Europe by a lovely Canadian couple named Louise and Norman, the huge, articulate home-away-from home was always immaculate. Gilles didn’t have to ask us to remove our shoes as we stepped in; it was a natural reflex

I don’t think Gilles knew too much about Carlos Reutemann prior to joining the Ferrari team in late 1977. As time passed, though, and as Carlos showed his class, Gilles began to respect him more and more. I had a long chat with Gilles in South Africa, 1978, the gist of which was, “Wow! I didn’t realize Carlos was that quick. I’m learning a lot from him. A lot…” I was also pretty close to Carlos at that point, so Gilles and I used to have a lot of laughs about Carlos’s idiosycrasies (of which there were many!). When Carlos won at Watkins Glen that year (and Gilles retired with a blown piston) he started a new thing, as in “Bloody Peter – for sure you and Carlos screwed my engine…” He didn’t always call me “Bloody Peter” after that – but he liked to joke about it when the mood was upon him. When I asked him to sign an excellent Chuck Queener print at The Glen in 1979 he therefore lost no time in reminding me about the events of a year before! That day in ’79, of course, Gilles was supreme in the drizzle, reminding everyone of how he could so easily have won the Championship that year instead of Jody. Indeed, Carlos spoke to Gilles before the 1979 Italian GP clincher and said, basically, “Don’t fool around with the Championship, Gilles. Don’t give it away. If you have a chance, take it. Championships are very hard to win. You may not get another chance.” Gilles replied, “Nah. I’ve promised Jody I’ll let him win. He’s going to help me win it in 1980…”