First, though, the build-up to that May 11, 1963, 15th International Trophy Race:

First, though, the build-up to that May 11, 1963, 15th International Trophy Race:

Indianapolis became a steep learning-curve as the month of May gathered pace. As well as embracing the ways of the idiosyncratic Speedway, and all that comes with it, Team Lotus faced the additional problems of being newcomers amongst the old guard, of initiating the winds of profound technical change and of trying many all-new components thus related. Like big, aluminium, 4.2 litre Ford Fairlane V8 engines. And Firestone tyres. And Halibrand wheels. And asymmetric suspension. And seat belts. And, yes, Bell Magnum helmets.

For most of the month of May, Jim, Colin Chapman and David Phipps, the talented photo-journalist, stayed in the house of Rodger Ward, the 1959 and 1962 Indy winner. The days were relaxed by European racing standards, beginning with early morning tests, lunch work, more afternoon laps and then late-ish nights with the mechanics after early evening meals. The issues were many: the Dunlop D12s were quicker (Dan Gurney had lapped his Lotus 29 at 150mph while Jim was racing in Europe) but the Firestones were more durable. With one pit stop to the roadsters’ two or three, Lotus could enjoy a big advantage even before the race was underway. To achieve that, however, they needed to run the less grippy Firestones.

This, in turn, caused a furore. Firestone built special tyres for Lotus around 15in wheels but then quickly found themselves under pressure from the Americans, who also expected the same, larger, footprint tyres for their roadsters (which normally ran 18in wheels). AJ Foyt in particular took umbrage. Expecting Firestone to be swamped, he approached Goodyear about using their stock car (NASCAR) tyres. They agreed. And, with that, the great Akron company began its single-seater racing history.

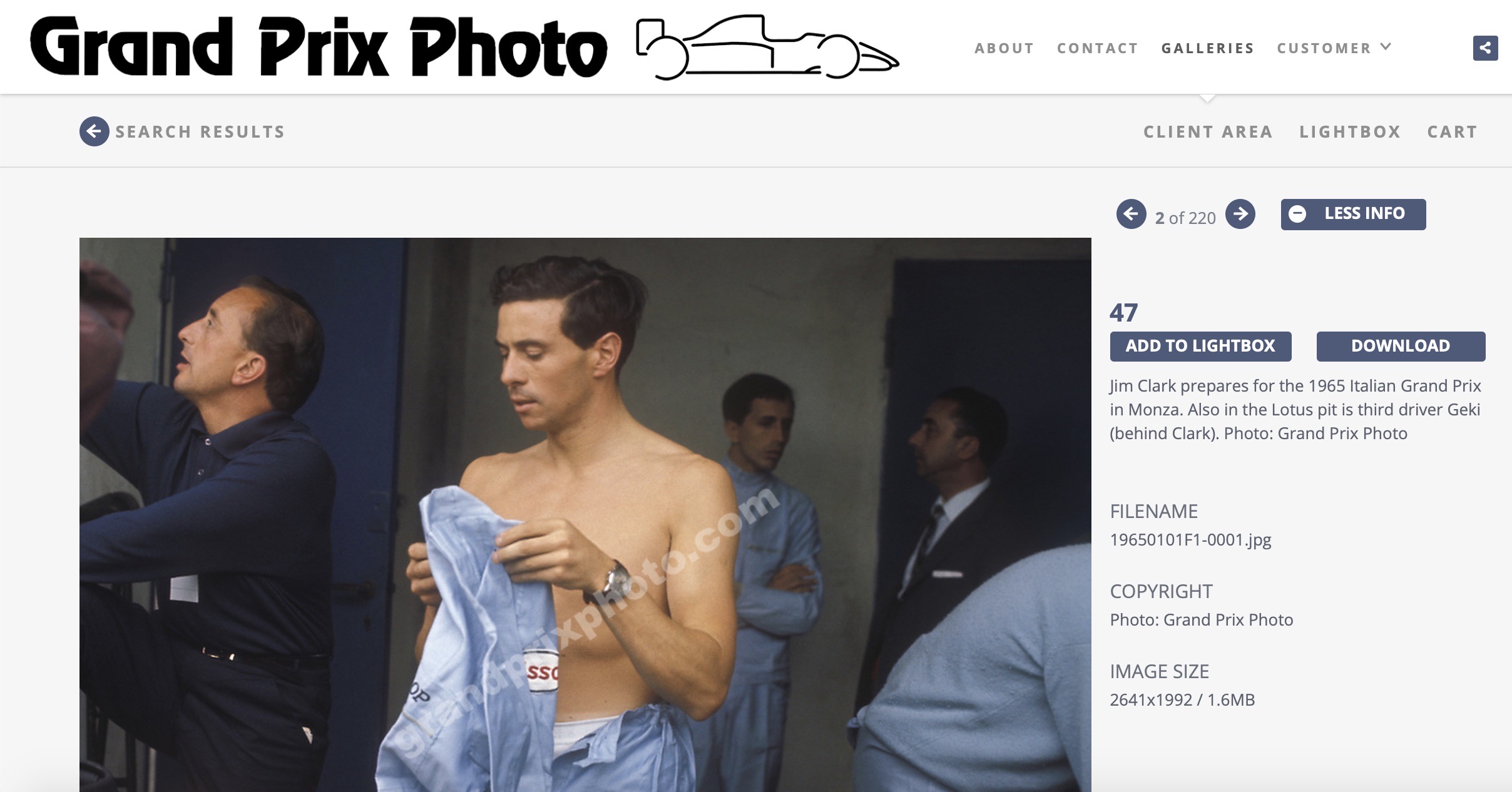

The switch to Firestones had additional implications for Jim. Until now, he had worn at Indy his regular, light blue, two-piece Dunlop overalls, complete with Esso and BRDC badges. With Ford’s engine supply now requiring the Lotus 29s to use Pure fuel and lubricants, those overalls were obviously redundant. What to do? Dan introduced Jim to Lew Hinchman, the local owner of a large garment and uniform factory. Lew, whose father, JB, built fire-retardant overalls for many of the American drivers, was in the process of making a dark blue, Ford-logo’d one-piece suit for Dan. Why not make one for Jim, too? Jim was measured up in the sweaty Team Lotus garage one lunch break (air-conditioning units were forbidden by the Speedway Safety Police due to the WWII-spec wiring in the garages!) and Jim was told that the overalls would be ready for the first week of qualifying. Dan also pointed Jim in the direction of the Bell Helmets race rep. Dan had been using a leather-edged McHal for a couple of years, and loved it. Even so, he was impressed with the new Magnum. And so here was a chance for Jim to put his trusty Everoak out to pasture. Jim examined the new silver helmet and decided to try it in the build-up to qualifying. For Silverstone, next weekend, he would nonetheless race with the Everoak – for the last time, as it turned out.

Between runs in this leisurely week at Indy, Jim also had time to shape-up his travel schedule for the following weeks. It would go something like this:

Tue, May 7: return to England (via Chicago). Pick up Lotus-Cortina at Heathrow. Drive to Silverstone. Check in to Green Man hotel. Thur-Fri-Sat: International Trophy F1 race, Silverstone. Sat, May 11: immediately after the race, fly with Colin and Dan Gurney to Heathrow in Colin’s Miles Messenger. Take flight to Chicago via New York. Change at Chicago for Indy. Check in to Speedway Motel. Begin testing Monday morning. Sat, May 18: Indy qualifying. Leave Sunday, May 19, for London. Stay with Sir John Whitmore in Belgravia. Two days at the factory at Cheshunt. Wed, May 22 : fly to Nice from Heathrow. Check in to La Bananerie at Eze sur Mer. Thur, May 23-Sun May 26: Monaco GP. Mon, May 27: leave at 4:00am for London. Take flight to Chicago and then on to Indy. Thur, May 30: Indy 500. Fri, May 31: fly to Toronto and then drive on to Mosport. Sat, June 1: Players’ 200 sports car race (with Al Pease’s Lotus 23). Drive afterwards to Toronto. Take evening flight to London. Mon, June 3: Whitmonday Crystal Palace sports car race (Normand Lotus 23B). Wed, June 5: Leave London with Colin for Spa (Belgian GP).

In other words: phew! There was of course no internet back then; transatlantic phone calls were both a novelty and expensive. Communications with the UK were via telexes and telegrams. Flight bookings were handled by Andrew Ferguson’s office in Cheshunt but re-arranged in the US by David Phipps. And the tickets, of course, were big, carbon-copied wads of coupons. Jim’s black leather briefcase was literally jammed to the hilt.

There was little time, though, as one Indy issue followed another, to wonder if it would all be feasible. If Jim didn’t qualify on the first weekend, for example – what would happen? Would he miss Monaco or would he foresake Indy? Given the powers behind the Indy effort – Ford, Firestone, etc – probably it would be Monaco. For now, though, it was heads-down: there was not a moment to spare – or even to think about the bigger problem.

In the midst of all this, Silverstone turned out to be a golden Saturday to be forever savoured. Thursday and Friday, by contrast, were best forgotten. Dunlop were pushing R6 development to new frontiers; Jim, as at Snetterton, found the Lotus 25 to be all over the place on the new tyres. On a cold and windy Thursday, jet lag or no, he couldn’t find anything approaching a sweet spot with the car – and this was with exactly the chassis (R5) in which he’d been so quick at Aintree (on R5s). He was only fifth that Thursday, focusing as he was on trying to make the car work just through Stowe and Club. If he could find a balance there, he reasoned, then he could probably make up for deficiencies over the rest of the lap.

The mechanics – Jim Endruweit, Cedric Selzer Dick Scammell, Derek Wilde and the boys – worked through to six o’clock on Friday morning, rebuilding Jim’s car with yet another set-up change. Perhaps, in addition, the rebuild might uncover a more fundamental chassis fault…

To no avail. Saturday was cold and wet; as all-weather as the new Dunlops undoubtedly were, little could be learned about a dry-weather balance. The grid therefore being defined by Thursday’s times, Jim tried team-mate Trevor Taylor’s car for a few laps. A spin at Copse capped an unremarkable day. Innes Ireland, what’s more, would start from the pole in the BRP Lotus 24-BRM – a chassis that Jim had always liked. Graham Hill was second in his trusty 1961/62 BRM, Bruce McLaren third in the new works Cooper and Jack Brabham fourth in his BT3, his engine down on power after a rushed rebuild. Poor Dan Gurney had flown over with Jim from Indy but for him there would be no F1 debut with Brabham: there was a dire shortage of Climax engines in this build up to the season proper, highlighted by Jack’s frequent runs up and down to Coventry. Jack was more than ready to let Dan race the one and only BT3 at Silverstone but a short test at Goodwood confirmed that Dan was much too tall for Jack’s cockpit. He would have to wait until Monaco to drive his tailor-made car.

This race was also notable for the appearance of the new 1963 Ferraris driven by John Surtees and Willy Mairesse. Powered by regular V6 engines (with V8s rumoured to be on the way), the new cars showed glimpses of promise amidst predictable teething troubles. This would be Surtees’ first F1 race for the Scuderia (and his first F1 race of the season; the beautiful Lola GT, a forerunner of the 1964 Ford GT and a car with which Surtees had been closely involved form the outset, also had its maiden appearance this Silverstone weekend. In a portent of the drama that was to explode three years later, Big John practiced the Lola on Thursday but was then forbidden by Ferrari from racing it on Saturday, even though the Sports Car Race was the last event of the day. John appointed Tony Maggs in his place; the South African started from the back of the grid and finished an excellent ninth.)

After Thursday’s all-nighter, and given the slight repairs that needed to be made to Trevor’s car after Jim’s spin, Colin decreed late on Friday afternoon that the boys should not overdo it. “Just put everything back to standard on both cars. Try to finish by nine. Get an early night.”

This they attempted. After packing the 25s back into the transporter and driving it to their regular garage on the outskirts of Towcester, they race-prepared the cars to standard spec before repairing to their hotel, the Brave Old Oak, in time for a half-past-nine drink at the bar. A “quick drink” then evolved into an all-nighter of a different kind – the liquid kind. Come Saturday morning, as the bleary-eyed Team Lotus crew hustled their transporter through the early-race traffic, all the talk was of the blonde girl who worked behind the bar…Princess Margaret and Lord Snowden attended the 1963 International Trophy; and the weather doffed its cap. A warm spring sun quickly replaced early cloud. One hundred thousand spectators poured through Silverstone’s gates, filling the grandstands and the grass banks right around the circuit. The British Grand Prix may have been but a couple of months in the future – here, at Silverstone – but the fans could not get enough. A clear example of how less is definitely not more – providing the product is right. In the Team Lotus transporter, between laughs, Jim Clark reflected on the good news: today they would forget the R6s. They’d race R5s. Dunlop wouldn’t like it but there you go. A race is a race.A masterpiece of a race. Jim started on the second row but was quickly up to second place, trailing his friend Bruce McLaren for a couple of laps before slicing past and pulling away. Suddenly he had a Lotus 25 around him. Suddenly he had balance and feel when on Thursday he been obliged to drive mainly on reflex, dumbing the understeer with induced flick oversteer. Now he was four-wheel-drifting the 25 through Copse, Becketts, Stowe and Club. Now he was using every inch of road through Woodcote and again past the pits, making the art of ten-tenths driving look sublimely simple.

He won it – and he won it with ease. It was a Clark Classic on the old R5s in Lotus 25/R5. Bruce finished second and Trevor drove well to make it a Team Lotus one-three. Innes, quick all weekend, finished fourth – but not before recovering from a big spin at Woodcote, the thick tyre smoke of which effectively ushered-in a new era – the era of the soft-compound Dunlop R6. Never before had rubber been so burnable – or so sticky. Innes revolved the 24 at high speed – probably on oil dropped by the Surtees Ferrari, which eventually retired – but kept the car on the Ireland. A few years before, the odds of that happening would have been too small even to contemplate. Now, if we can combine those new grip levels with more compliant sidewalls, thought Jim and Colin, then we’ll definitely have a race tyre…

He won it – and he won it with ease. It was a Clark Classic on the old R5s in Lotus 25/R5. Bruce finished second and Trevor drove well to make it a Team Lotus one-three. Innes, quick all weekend, finished fourth – but not before recovering from a big spin at Woodcote, the thick tyre smoke of which effectively ushered-in a new era – the era of the soft-compound Dunlop R6. Never before had rubber been so burnable – or so sticky. Innes revolved the 24 at high speed – probably on oil dropped by the Surtees Ferrari, which eventually retired – but kept the car on the Ireland. A few years before, the odds of that happening would have been too small even to contemplate. Now, if we can combine those new grip levels with more compliant sidewalls, thought Jim and Colin, then we’ll definitely have a race tyre…

It was a fun day, too. Sir John Whitmore was again magnificent in the Cooper S; Mike Beckwith won his class with the Normand Lotus 23B; Jack Sears scored the first of his many wins with the big Ford Galaxie – a car that Jim had driven over at Indy, when he was filling in some time one quiet day at the Speedway;  Graham Hill won the GT race in John Coombs’ lightweight E-Type; and Denny Hulme again won the Formula Junior race in the factory Brabham, just beating David Hobbs and Paul Hawkins. Earlier that week, Jack himself had driven the FJ car, helping Denny with set-up and with a few circuit pointers. Then there was the business with the Miles Messenger. Racing over, Jim and Dan piled into the cramped four-seat cockpit; bags were stuffed into the small luggage compartment (no room for the trophy!); Colin fired up the DeHaviland Gipsy engine, opened the throttle…and nothing happened. The old four-seater remained bogged in the Stowe mud, its wheels intransigent. Out jumped an amused Silverstone winner and his buddy, Dan – and off, in a lighter Miles, set Colin. Even as the little aeroplane was gathering speed, Jim and Dan were scambling aboard.

Graham Hill won the GT race in John Coombs’ lightweight E-Type; and Denny Hulme again won the Formula Junior race in the factory Brabham, just beating David Hobbs and Paul Hawkins. Earlier that week, Jack himself had driven the FJ car, helping Denny with set-up and with a few circuit pointers. Then there was the business with the Miles Messenger. Racing over, Jim and Dan piled into the cramped four-seat cockpit; bags were stuffed into the small luggage compartment (no room for the trophy!); Colin fired up the DeHaviland Gipsy engine, opened the throttle…and nothing happened. The old four-seater remained bogged in the Stowe mud, its wheels intransigent. Out jumped an amused Silverstone winner and his buddy, Dan – and off, in a lighter Miles, set Colin. Even as the little aeroplane was gathering speed, Jim and Dan were scambling aboard.

Four connections and 4,000 miles later, the two Team Lotus friends were at Indy, ready to test on a warm Monday morning.

Captions from top: Dan Gurney, in new Hinchmans, Colin Chapman and Jim Clark, still in Dunlop blues, talk wheels and tyres early in the Indy month of May; Jim fingertips 25/R5 out of Becketts en route to victory; late in ’62 Jim had fun at the Speedway with a road-going Mercury Monterey. Images: LAT Photographic, Indianapolis Motor Speedway. For more on Hinchman overalls: http://hinchmanracewear.com

Posted in

Days Past,

F1,

Jim Clark's 1963 season and tagged

Bell Helmets,

Clark,

Dan Gurney,

Dunlop,

Ferrari,

Firestone,

Goodyear,

Gurney,

Hinchman,

indianapolis,

Indy,

Jim Clark,

Lotus,

Scotland,

Silverstone,

Team Lotus

For all his cool headgear, Jean-Eric Vergne (below,top) is much more Jean-Pierre Jarier than he is Francois Cevert. A wide, soft approach. Lots of aggression with the brakes, the steering and the release of same. Lots of car-control, of course, but none of the straight lines that typified Francois, particularly in 1973. Daniel Ricciardo (below,bottom) exhibited a slightly shorter corner and more seamless transitions. Like McLaren, Toro Rosso have two “long corner” (but very skilful, very spectacular) drivers.

For all his cool headgear, Jean-Eric Vergne (below,top) is much more Jean-Pierre Jarier than he is Francois Cevert. A wide, soft approach. Lots of aggression with the brakes, the steering and the release of same. Lots of car-control, of course, but none of the straight lines that typified Francois, particularly in 1973. Daniel Ricciardo (below,bottom) exhibited a slightly shorter corner and more seamless transitions. Like McLaren, Toro Rosso have two “long corner” (but very skilful, very spectacular) drivers.

Pastor Maldonado, as stated earlier, was almost scary to watch at Rascasse, if only because his Alesi-like turn-in (and feel) leaves him absolutely no margin at all in terms of the inside rear and the apex. With Grosjean, you’re always thinking “exit oversteer”; with Pastor (below, top) it’s “early commitment”. He looked knife-sharp from where I sat – and up at Casino Square, where he was blindingly late on the brakes, he was jaw-droppingly fearless – the more so because the Williams is still a difficult car. This was the best Pastor has looked so far this year. Valtteri (below, bottom), by contrast, was for me a bit disappointing – if only because one’s expectations are always so high with this guy. A relatively wide and frequently brake-locked approach was compromised by minimum speeds too high by far: the back end would judder out, Walter would have to lift, opposite lock would be applied…and finally he was out of there. It was uncomfortable to watch and probably not much fun to execute. I’m sure it’ll be better by Sunday…

Pastor Maldonado, as stated earlier, was almost scary to watch at Rascasse, if only because his Alesi-like turn-in (and feel) leaves him absolutely no margin at all in terms of the inside rear and the apex. With Grosjean, you’re always thinking “exit oversteer”; with Pastor (below, top) it’s “early commitment”. He looked knife-sharp from where I sat – and up at Casino Square, where he was blindingly late on the brakes, he was jaw-droppingly fearless – the more so because the Williams is still a difficult car. This was the best Pastor has looked so far this year. Valtteri (below, bottom), by contrast, was for me a bit disappointing – if only because one’s expectations are always so high with this guy. A relatively wide and frequently brake-locked approach was compromised by minimum speeds too high by far: the back end would judder out, Walter would have to lift, opposite lock would be applied…and finally he was out of there. It was uncomfortable to watch and probably not much fun to execute. I’m sure it’ll be better by Sunday…

Sauber’s pair, by contrast, were surprisingly different from one another. Nico Hulkenberg (below, top) had more initial steering input than, say, Romain Grosjean, and a longer corner than Daniel Ricciardo. He played with the throttle early and, like Alonso, always gave himself a touch of oversteer before main rotation just beyond this photograph. He gives the impression, in other words, of asking quite a lot from the tyres and, of course, from the car. Esteban Gutierrez (below, bottom) was for me probably the most surprising driver of the session. He was neat, composed, early into the corner, and displayed lots of good handwork and mid-corner patience. He wasn’t the quickest guy out there, of course, but this was a good way to start a Monaco weekend. From here he has a useful platform from which to build.

Sauber’s pair, by contrast, were surprisingly different from one another. Nico Hulkenberg (below, top) had more initial steering input than, say, Romain Grosjean, and a longer corner than Daniel Ricciardo. He played with the throttle early and, like Alonso, always gave himself a touch of oversteer before main rotation just beyond this photograph. He gives the impression, in other words, of asking quite a lot from the tyres and, of course, from the car. Esteban Gutierrez (below, bottom) was for me probably the most surprising driver of the session. He was neat, composed, early into the corner, and displayed lots of good handwork and mid-corner patience. He wasn’t the quickest guy out there, of course, but this was a good way to start a Monaco weekend. From here he has a useful platform from which to build.

Jules Bianchi (below, top) was much tighter on approach than Max Chilton (below, bottom); indeed, Jules was as early, and as rhythmic with his hand- and footwork, as Paul Di Resta. Despite that sort of talent alongside him, Max Chilton has nonethless chosen to go the long-corner way. Yes, it leaves him more margin for error, particularly on a circuit like Monaco; no, it isn’t as efficient.

Jules Bianchi (below, top) was much tighter on approach than Max Chilton (below, bottom); indeed, Jules was as early, and as rhythmic with his hand- and footwork, as Paul Di Resta. Despite that sort of talent alongside him, Max Chilton has nonethless chosen to go the long-corner way. Yes, it leaves him more margin for error, particularly on a circuit like Monaco; no, it isn’t as efficient.

I couldn’t see much difference between the two Caterham drivers, Charles Pic (below, top) and Guido van der Garde (below, bottom). Charles was pretty neat and tidy through the fourth-gear esses in Malaysia but here he was definitely giving himself a nice, soft corner entry with plenty of initial steering input. Likewise Guido, which must be a bit frustrating for the engineers.

I couldn’t see much difference between the two Caterham drivers, Charles Pic (below, top) and Guido van der Garde (below, bottom). Charles was pretty neat and tidy through the fourth-gear esses in Malaysia but here he was definitely giving himself a nice, soft corner entry with plenty of initial steering input. Likewise Guido, which must be a bit frustrating for the engineers.