They drove, despite their misgivings, on the Friday. The steep Monza banking had long since established itself as the fastest race track in the world – some 30 mph faster even than Indianapolis. The British teams, wary of the damage caused by the bumps, had boycotted the Italian GP in 1960. Phil Hill had that day won for Ferrari, thus becoming the last driver ever to secure a World Championship victory in a front-engined Grand Prix car. Seat belts had appeared for the first time in Europe at the Races of Two Worlds in 1957-58 but not for the usual reasons – not because the drivers believed in not being thrown from their cars in the case of accident. They were worn just to keep the drivers in the cars while they were running… (That combined Indy-F1 race, incidentally, was run in heat form for the simple reason that the teams needed time to rebuild their cars after each segment. Had the race been run non-stop it is unlikely there would have been any finishers.) Ferrari’s Luigi Musso took the pole for the 1958 race at an average speed of nearly 170mph (281kph).

They drove, despite their misgivings, on the Friday. The steep Monza banking had long since established itself as the fastest race track in the world – some 30 mph faster even than Indianapolis. The British teams, wary of the damage caused by the bumps, had boycotted the Italian GP in 1960. Phil Hill had that day won for Ferrari, thus becoming the last driver ever to secure a World Championship victory in a front-engined Grand Prix car. Seat belts had appeared for the first time in Europe at the Races of Two Worlds in 1957-58 but not for the usual reasons – not because the drivers believed in not being thrown from their cars in the case of accident. They were worn just to keep the drivers in the cars while they were running… (That combined Indy-F1 race, incidentally, was run in heat form for the simple reason that the teams needed time to rebuild their cars after each segment. Had the race been run non-stop it is unlikely there would have been any finishers.) Ferrari’s Luigi Musso took the pole for the 1958 race at an average speed of nearly 170mph (281kph).

No surprise, then, that Jack Brabham led the tentative, pre-Italian GP boycott in 1963. The banking had not been used in 1962, so why revert to it now? When push came to shove, however, Black Jack and Dan were out there on Friday morning, nosing around.

Jim Clark and Colin Chapman, already wary of Italian politics (following the Von Trips accident of 1961) stayed relatively neutral. Jim had a World Championship to clinch. Ferrari had new cars and engines to beat. They settled into the Hotel de la Ville, opposite Monza’s Villa Real, with some trepidation. Monza – Italy – is never easy.

And so onto the banking they ventured that Friday morning, ride heights raised, suspension stiffened…pick-up points stressed. The combined road-course/oval shared the same pit straight, divided only by cones (the oval’s straight nearest the pits). The oval was flat-out in top gear; the road course was pretty much as we know it today, minus the first, second and Ascari chicanes. Team Lotus initially sent out Mike Spence (in the carburettored car, standing-in for the injured Trevor Taylor). His 2min 48.1 was beaten only by the BRMs of Richie Ginther and Graham Hill and Masten Gregory in his Parnell Lotus 24-BRM. Brave stuff.

Then Bob Anderson crashed when his privately-entered Lola-Climax lost a wheel on the banking; luckily he was uninjured. The teams suddenly became adamant: unless they raced only on the road course there would be no Italian Grand Prix. The Automobile Club of Milan acquiesced only moments before the GPDA handed in its petition. The banking was shut off. Although it would be used by sports cars through to 1969 (slowed by entrance chicanes from 1966 onwards), the Monza banking never again played host to F1.

Somewhat disrupted, therefore, but much happier, the teams set about their new challenge – an Italian GP on the familiar, 1962, layout. For Jim, problems quickly arose. He was hoping to race the new Hewland gearbox tried in Austria but quickly it failed. Reverting to his regular ZF gearbox, Jim qualified only third, 1.7 sec slower than John Surtees in the new monocoque Ferrari V6. Lorenzo Bandini, making his debut with the older, space-frame Ferrari, was behind Jim and alongside Dan Gurney on the third row. With the monocoque BRM also performing well in the hands of Graham Hill, who qualified second, Monza was looking as though it was going to be very different from the season’s previous high-speed race, at Reims.

In the end, it was the usual, nail-biting slipstreamer. The lead changed no fewer than 25 times before it was finally settled in favour of Jim Clark. For Jim, though, his forehead protected by white masking tape, the better to stop his Bell Magnum from creeping up in the slipstream, the day was bittersweet, as he recounted in Jim Clark at the Wheel: “Being so much slower than John in practice really sapped my confidence, and I felt dismal on Friday and Saturday. It got so bad that, before the race started, I had fitted a new engine, gearbox, gear ratios, reverted to the standard windscreen and changed the tyre sizes. This meant starting the race not fully knowing what the car would be like when it arrived at the first corner. From the start, though, the car was better. In Surtees’ tow I could gain an extra 500rpm and by the third lap I could relax a little and still maintain my position behind him while, behind me, Graham and Dan were having their own private battle. On about the 17th lap I noticed a puff of smoke from the tailpipes of John’s Ferrari. It was no surprise when he dived into the pits the following lap.

“This left me in the lead but with a problem on my hands. It was not worthwhile stretching myself or the car so long as Graham and Dan were behind me, towing one another around. I was basically a sitting duck and when they passed me I remember they whisked by so quickly that they almost caught me on the hop. I then managed to get into their slipstream. The three of us had a grand race of it before Graham retired. Dan and I then had a great set-to, for our cars were fairly equal in performance. I remember at one stage coming up to lap Innes Ireland in the BRP-BRM. He was much quicker than both Dan or I down the straights but we had him on the corners. I first tried on one bend to get past on the inside but Innes blocked me off. Then I tried again and the same thing happened.

“The next time around I thought I would play it crafty, so I waited until Dan had come up close behind me and I made a pass at Innes. I eased off slightly and let Dan go through. Innes thought that Dan was me and moved over again – but no-one does this sort of thing to Dan. In the ensuing battle of wits Dan eased Innes out, and while he was doing that I passed both of them.” (Ireland, whose relationship with Jim had been strained ever since he had been dropped from Team Lotus at the end of 1961, would have finished third at Monza but for an engine failure on the last lap; as it was he came home P4). “Dan had to retire shortly afterwards with fuel starvation and I was able to settle down at last to win the Italian Grand Prix and assure myself of the World Championship.

“I couldn’t believe it when I arrived at the pits after my slowing-down lap. The place was crowded with photographers and Colin had a bit of a fight getting through to me. However, he managed it and he climbed on the back of the Lotus with the silver trophy and we covered a lap of honour, picking up Mike Spence, who had broken down on the back of the circuit while heading for sixth place.

“Colin and our wonderful team of mechanics were ecstatic. It gave me great pleasure to share this victory with them. To escape the mob afterwards we dived into the Dunlop enclosure, where someone came up and informed me that the Italian police wanted to see me immediately in race control. When I got there, I discovered they wanted me to sign a document written in Italian relating to the Von Trips accident of 1961. I naturally refused to sign it. Coming as it did on what should have been a night of celebration, this affair depressed me so much that all I wanted to do was get out of Italy. I didn’t care if I never returned to the place. Consequently, it was a very subdued victory party at the de la Ville, enlivened only by a bun fight between the Lotus and Cooper teams.”

Jim flew home early on Monday with Jack Brabham in the latter’s Cessna 180. He headed straight for Balfour Place – and then to a press conference in Fleet Street, home of the British daily press. Most of the questions, sadly, related to 1961, not 1963.

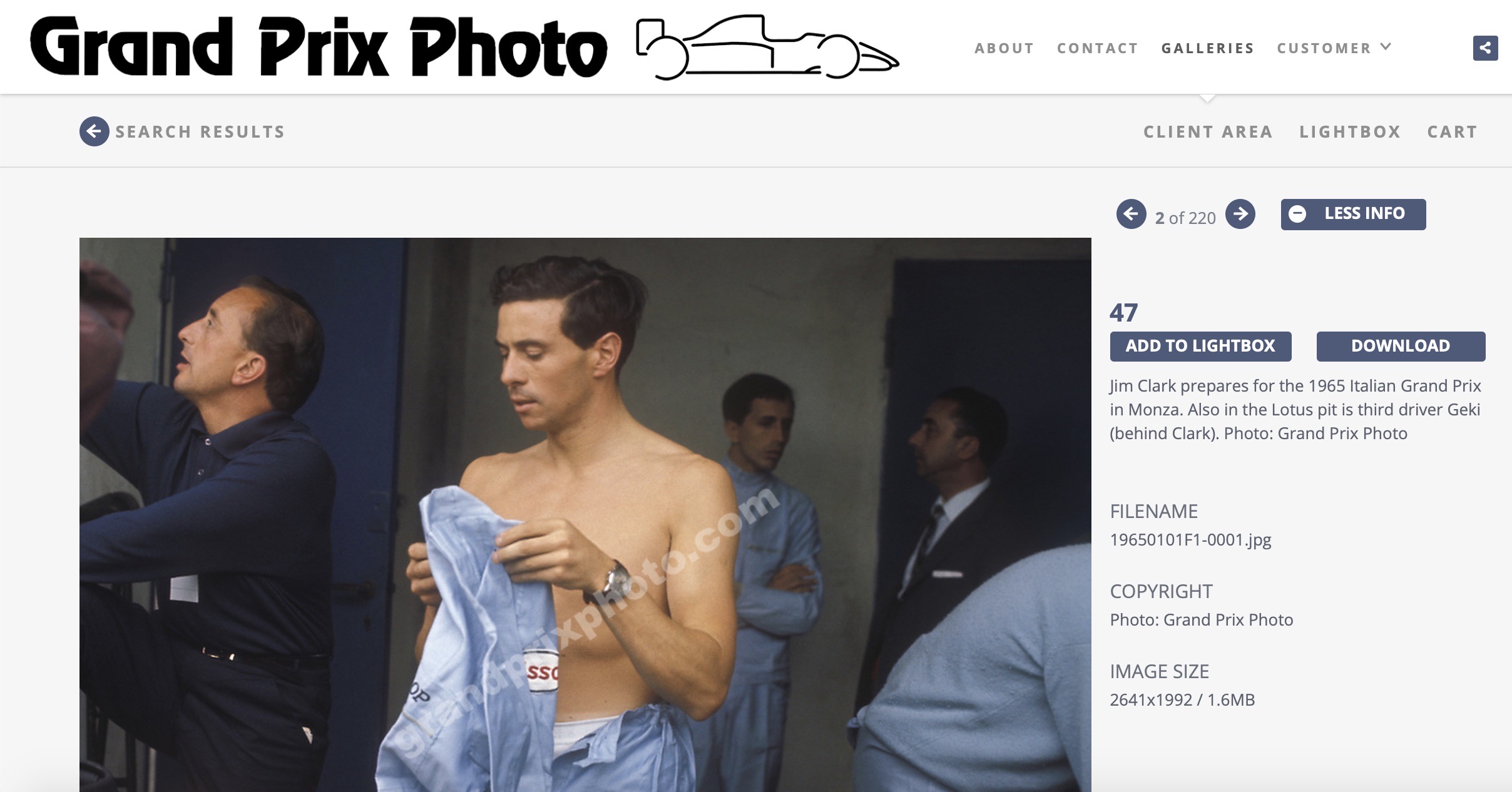

Captions (from top): although he feared the worst, Jim eventually won convincingly. With five wins and a second place to his credit from seven starts, he clinches the 1963 World Championship; early on Friday morning, John Surtees tries both the Monza banking and the new Ferrari V6. He was easily quickest in qualifying but retired with engine failure (broken tappet). Team Lotus, then, won the race of reliability!; the combined road course/banking layout as drawn by the excellent (but sadly now defunt) Italian weekly, Auto Italiana, in its preview to the 1963 Italian GP; Auto Italiana‘s explanation of how the complex Monza pit straight/pit lane system was going to work (with banking in use) for 1963, a new, higher pit wall was built; Jim’s 25 was extensively re-fitted and revised before the race; Surtees leads Jim and then Graham Hill and Dan Gurney into the Parabolica in the early laps; Chris Amon (pictured here talking early on Friday to Eoin Young (probably about the new Bruce McLaren Cooper team that would contest the 1964 Tasman Series!) was lucky to escape a big practice accident at the Lesmos with broken ribs; rearward view of the aforementioned lead group; front cover of Auto Italiana in the week after the race. Two artists here – Jim Clark and Giovanni Bertone; below – to the backdrop of the Lotus truck, and before the drama with the Italian authorities, Jim McKay interviews Colin and Jim for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Images: LAT Photographic, Peter Windsor Collection

At Goodwood over the weekend we celebrated the 50th anniversary of Jim Clark’s first World Championship with probably the greatest collection of Clark cars ever seen on one patch of motor racing turf. On Saturday, September 14, 1963, there was a similar, if slightly more muted, Jim Clark parade to toast the same championship win. Jim, Colin Chapman and the Team Lotus mechanics were the impromptu toast of a relatively small crowd at Brands Hatch, where a BRSCC international meeting had the week before been billed only as the Anglo-European Trophy for Formula Juniors. Jim changed into his Dunlop overalls in order to drive the Lotus 25 around the Grand Prix circuit, waving to the crowd and carrying Colin Chapman piggy-back behind the rollover bar; and all the Team Lotus mechanics were present, sharing the fun and chatting to the crowds. Behind the 25 ran the Ron Harris Lotus 27s of Peter Arundell and Mike Spence (who were racing that day and would finish one-four in the final) plus the spare 27, an Elite, an Elan, a Seven and a Cortina.

At Goodwood over the weekend we celebrated the 50th anniversary of Jim Clark’s first World Championship with probably the greatest collection of Clark cars ever seen on one patch of motor racing turf. On Saturday, September 14, 1963, there was a similar, if slightly more muted, Jim Clark parade to toast the same championship win. Jim, Colin Chapman and the Team Lotus mechanics were the impromptu toast of a relatively small crowd at Brands Hatch, where a BRSCC international meeting had the week before been billed only as the Anglo-European Trophy for Formula Juniors. Jim changed into his Dunlop overalls in order to drive the Lotus 25 around the Grand Prix circuit, waving to the crowd and carrying Colin Chapman piggy-back behind the rollover bar; and all the Team Lotus mechanics were present, sharing the fun and chatting to the crowds. Behind the 25 ran the Ron Harris Lotus 27s of Peter Arundell and Mike Spence (who were racing that day and would finish one-four in the final) plus the spare 27, an Elite, an Elan, a Seven and a Cortina.  Jim would have enjoyed watching the two FJ heats early in the afternoon (won by Timmy Mayer and Denny Hulme) and would have been delighted by Sir John Whitmore’s class win with the factory Austin Cooper S. Bob Olthoff would have revived recent happy memories by winning overall with his Galaxie; and Jack Sears would also have brought a smile to Jim’s face with his class win with his Willment Cortina GT. (The Cortina-Lotus would soon be homologated but not for this weekend). That done, Jim then donned his Bell Magnum and string-backed Leston gloves to set about some serious lappery with the 25. Despite running the wrong dampers for Brands, and nursing a slight mis-fire, he completed four flying laps, smashing Bruce McLaren’s 2.5 litre record by 0.6sec. (The first Championship F1 race at Brands, the British and European GP, was scheduled for July, 1964.)

Jim would have enjoyed watching the two FJ heats early in the afternoon (won by Timmy Mayer and Denny Hulme) and would have been delighted by Sir John Whitmore’s class win with the factory Austin Cooper S. Bob Olthoff would have revived recent happy memories by winning overall with his Galaxie; and Jack Sears would also have brought a smile to Jim’s face with his class win with his Willment Cortina GT. (The Cortina-Lotus would soon be homologated but not for this weekend). That done, Jim then donned his Bell Magnum and string-backed Leston gloves to set about some serious lappery with the 25. Despite running the wrong dampers for Brands, and nursing a slight mis-fire, he completed four flying laps, smashing Bruce McLaren’s 2.5 litre record by 0.6sec. (The first Championship F1 race at Brands, the British and European GP, was scheduled for July, 1964.) That night, with the less pleasant aspects of Monza now beginning to fade, Colin Chapman hosted a huge party in his house in Hadley Wood, near Elstree aerodrome in north London. Most of Jim’s peers were present, in addition to many key motoring and motor racing figures. I asked Sally (Stokes) if she remembered much about it. “I think it was the first time I saw Jim in a kilt,” she replied. “There were lots of ‘do they/don’t they?’ jokes which Jim thought were very funny. Apart from that I don’t remember too much about it. Probably we were having too good a time!”

That night, with the less pleasant aspects of Monza now beginning to fade, Colin Chapman hosted a huge party in his house in Hadley Wood, near Elstree aerodrome in north London. Most of Jim’s peers were present, in addition to many key motoring and motor racing figures. I asked Sally (Stokes) if she remembered much about it. “I think it was the first time I saw Jim in a kilt,” she replied. “There were lots of ‘do they/don’t they?’ jokes which Jim thought were very funny. Apart from that I don’t remember too much about it. Probably we were having too good a time!”