Clark brilliant at Aintree

Jim Clark’s 1963 racing schedule now begins to gather real pace. The back-to-back early-season European non-championship F1 races behind him, Jim returns to the farm for a couple of days before driving the 225 miles down to Liverpool for his third non-title F1 race of the season, the Aintree 200. (Jim will drive approximately 40,000 road miles in 1963.) At Edington Mains there is always farm work with which to keep abreast but in addition there is plenty of racing-related admin, the relevant papers of which he files in his red leather desk folder. A good example of Jim’s meticulous attention to detail can be seen in his correspondence with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although the Team Lotus entries and surrounding paperwork are handled by Andrew Ferguson and – for Indy, 1963, also by David Phipps, the tall photo-journalist who had become a close friend of Colin Chapman – Jim receives a personal letter from the Speedway’s Henry Banks, inviting him to take part in an upcoming race at Indianapolis Raceway Park. Bearing in mind that the FIA inter-change between drivers licenced to different sanctioning bodies was a brand new thing in America, Henry’s letter to Jim, detailing an “all-comers’” race on April 28, in retrospect seems logical. The exact description of the event – “a 300-mile race for American-manufactured cars in the improved touring category (or what would later be known as NASCAR’s Yankee 300!)” – obviously catches Jim’s attention because his written reply is as follows: “Unfortunately, like Dan Gurney and Jack Brabham, I am flying back and forth between Europe and America at the moment and on that particular date we are scheduled to race at Aintree here in Britain…”

Jim Clark’s 1963 racing schedule now begins to gather real pace. The back-to-back early-season European non-championship F1 races behind him, Jim returns to the farm for a couple of days before driving the 225 miles down to Liverpool for his third non-title F1 race of the season, the Aintree 200. (Jim will drive approximately 40,000 road miles in 1963.) At Edington Mains there is always farm work with which to keep abreast but in addition there is plenty of racing-related admin, the relevant papers of which he files in his red leather desk folder. A good example of Jim’s meticulous attention to detail can be seen in his correspondence with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although the Team Lotus entries and surrounding paperwork are handled by Andrew Ferguson and – for Indy, 1963, also by David Phipps, the tall photo-journalist who had become a close friend of Colin Chapman – Jim receives a personal letter from the Speedway’s Henry Banks, inviting him to take part in an upcoming race at Indianapolis Raceway Park. Bearing in mind that the FIA inter-change between drivers licenced to different sanctioning bodies was a brand new thing in America, Henry’s letter to Jim, detailing an “all-comers’” race on April 28, in retrospect seems logical. The exact description of the event – “a 300-mile race for American-manufactured cars in the improved touring category (or what would later be known as NASCAR’s Yankee 300!)” – obviously catches Jim’s attention because his written reply is as follows: “Unfortunately, like Dan Gurney and Jack Brabham, I am flying back and forth between Europe and America at the moment and on that particular date we are scheduled to race at Aintree here in Britain…”

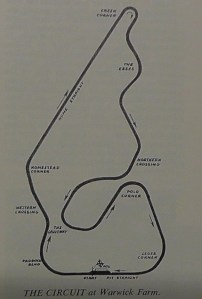

As he sits at his desk, Jim also takes stock of his upcoming schedule. Hectic travel is of course not new to him: early in 1961 he competed in three New Zealand internationals before embarking on his European season – and he had finished that year, and begun 1962, with four South African races, an outing at Daytona in a Lotus Elite and then a one-off race in a Lotus 21 in Sandown Park, Australia. What now lay ahead, however, takes him into new territory. Following Saturday’s Aintree 200, Jim and Colin will fly immediately back to Indy via Chicago (Jim’s third trip to the States since January). There they will continue to run the Lotus 29s at the Speedway before returning on May 7, with Dan Gurney now joining the group, to race at Silverstone in the Daily Express Trophy meeting. Then it will be back to Indy again, this time for qualifying, before flying back for the Monaco and European GP on May 26. (Assuming Jim qualifies on the first weekend, that is: if rain intervenes, or they run into problems, Jim would then have to miss Monaco in order to qualify at Indy on the second weekend.) Following Monaco, he, Dan and Colin will then fly back to Indy for the race the following Thursday (Memorial Day). Jim will then drive to Mosport to race in the Players 200 two days later, catch a Toronto flight to London that night and race at Crystal Palace, in the Normand Lotus 23B, on June 3 (Whitmonday). Nor will there be a break after that, for the Belgian GP at Spa is scheduled for the weekend of June 7-8-9.

Jim takes all of this merely as part of his job. Comets and Boeing 707s make flying more fun than it had been in the turbo-prop days – and economy seats are relatively wide and relatively long. You can actually sleep on a trans-Atlantic flight – and the immediate necessity to have to drive a racing car does away with jet lag. Beyond that, Jim’s parents had never wanted him to race. Now, with this sort of schedule, and with reasonable chances ahead of him for some good results, he can at least justify racing as a profession from which he can earn a living.

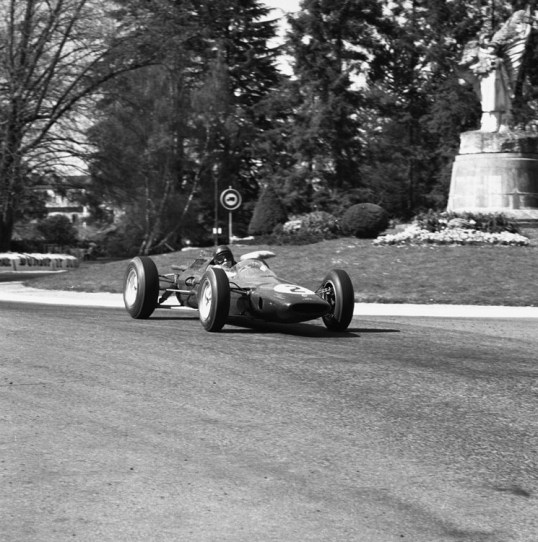

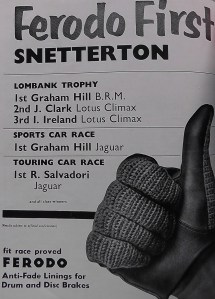

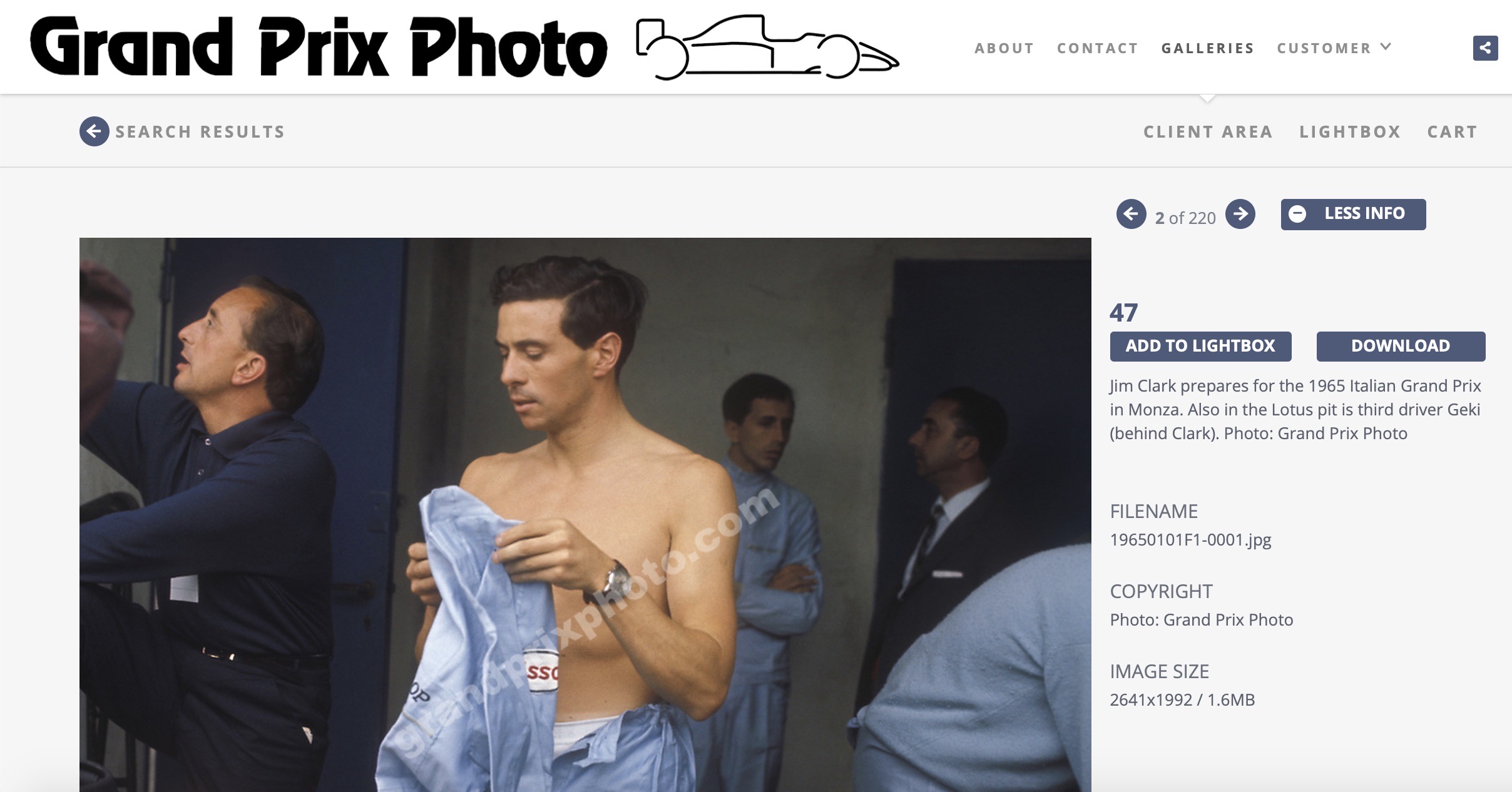

Aintree is bathed in sunshine on Friday, April 26 – and Jim, running the Lucas fuel-injected Lotus 25, feels as good in the car as he had at Pau and Imola. Compared with the carburettored 25 of 1962, the fuel-injected 25 provides a more useable power band, particularly at low revs. The new short-stroke Climax engine can also be revved higher, additionally enhancing torque and power. The biggest talking-point in the Team Lotus truck is actually of the ZF gearbox and the ongoing problem of the thing jumping out of gear (a subject Colin Chapman prefers his drivers not to mention to the press!). The root cause of the issue is that the ZF was basically a four-speed gearbox adapted to take an extra cog. The welds, reduced to a minimum, habitually came away from the spline.Trevor Taylor’s car occasionally runs a strong, heavier Colotti five-speed gearbox but Chapman does not want to compromise weight on the number one Clark car. He continues to work away with pencil drawings whenever he has a spare moment but an ultimate fix will not achieved until new ZF gearboxes, with the selector mechanism on the side of the gearbox, are fitted for 1964. For now, Jim spends so much time wondering if the 25 is going to jump out of top that he begins to develop a one-handed driving style, steering with the left hand and holding the car in gear with his right. Jim also has reservations about the new Dunlop R6s. He hadn’t liked them at Snetterton, where the 25 had felt more skittish than at any time in its life – and he had used last year’s R5s (based on the older D9 and D12 tyres) at Pau and Imola. He would do so again at Aintree but Dunlop are keen to try a new version of the R6 at Silverstone in two weeks’ time. (Talking about Snetterton, Jim is a little surprised to see Denis “Jenks” Jenkinson write in the latest edition of Motor Sport that Graham Hill had won in the wet there because “Jim Clark was out of practice, Hill having raced in Australia and New Zealand over the winter.” So Jim’s endless testing of the Lotus 29 hadn’t counted?

Jim is easily fastest on Aintree Friday, loving the circuit on which he had won the British GP in 1962 – and the 1962 Aintree 200 (in the Lotus 24: he had also been quick in the wet at Aintree in 1961, before the Lotus 21 blew an oil pipe.). Strangely, though, he looks unfamiliar in the Lotus 25 on Friday, wearing, as he is, the older, 1961-spec, smaller-eyepiece, goggles he’d last worn at Zandvoort in 1962. For race day, Jim switches to his customary wide-lens Panoramas (with black tape across the top-third of the lens). Still he wears his trusty, stone-nicked dark blue, peakless Everoak.

Despite the unchanged R5s, Jim’s pole time had been 1.2 sec faster than his fastest practice lap at the British GP the previous July. Jack Brabham is second, 0.8 sec slower in his 1962 BT3, but non-starts when his Climax engine throws a piston late on Friday. (This failure has the knock-on effect of delaying the completion of Dan Gurney’s new Brabham for the Daily Express Trophy, ensuring that Dan will remain a frustrated spectator after the long flight over from Indy. It is probably because of some of these dramas, and because Dan had initiated the Lotus Indy programme in the first place, that Colin Chapman will have no compunction about lending Jack Brabham a Lotus 25 for the Monaco GP a few weeks later.)

Graham Hill, who at Aintree is still in his 1962-spec BRM, is 0.8 sec quicker than he’d been the previous July – but slower than Innes Ireland, who is very fast in the Goodwood-winning BRP Lotus 24-BRM. Ireland qualifies third, Hill fourth and Ritchie Ginther fifth, equaling his team-leader’s time in the second BRM. Trevor, again in gearbox trouble, will start from the inside of the third row in the carburettored Lotus 25.

What should have been a Clark walkover under leaden skies on Saturday turns out to be one of the best races of the 1963 season. The record crowd at the famous Grand National venue can hardly believe it when Jim Clark’s hand goes up at the start and the field swarms around him. With the 25’s battery completely flat, Jim is totally helpless. Ted Woodley and the boys push the car over to the pits, fit a new battery – and the car starts perfectly. Jim leaves the pits even as the field is well into its second lap.

Clark drives brilliantly in these early stages but clearly the car still isn’t right. A fuel-injection-related mis-fire comes and goes. Trevor, meanwhile, is running fifth and looking good.

On lap 16 Colin Chapman thus makes the sort of decision that even the most hardened of Team Principals always dread: he pulls in both of his drivers and instructs them to swap cars. (I spoke only a couple of days ago to Anita Taylor, Trevor’s sister, about this. “Trevor was only too ready to oblige,” she said. “Of course he wanted to win. He was also a friend of Jimmy’s, a colleague, a huge admirer. If Chapman thought it was best for the team, Trevor went along with it. He was that sort of man.”)

It is a beautifully-orchestrated manoeuvre. Jim comes in first and is ready, waiting, as Trevor screams to a halt. Out jumps Trevor and quickly Ted Woodley swaps seats. In slides Jim. He has the rear Dunlops alight before Ted is even clear of the car.

So Jim Clark is now in Lotus 25 Number 4 and Trevor in Lotus 25 Number 3. Out in front, Ritchie Ginther gives best to Graham after taking an early lead; Innes is third, followed by Bruce McLaren in the new 1963 Cooper 66-Climax.

Jim Clark then produces a supreme display of class driving, perfectly-balancing the carburettored 25 through Aintree’s medium-speed corners, blipping the throttle on the slow ones to keep the revs in the useable band. He works his way back to an eventual third place. His lap times are consistent to within tenths; his fastest lap – a staggering 1min 51.8sec – is 0.6 quicker than his pole time and a full 1.8sec quicker than his pole lap at the British GP in ’62. This in a car with the 1962-spec, 175bhp engine.

Afterwards, Jim says simply this: “I really enjoyed this race – even though I didn’t win it; I enjoyed it more than a number of the Grand Prix events I was to drive during the season.”

Graham Hill wins Aintree (from Innes Ireland, Jim/Trevor, Ritchie, Bruce, Chris Amon in the Reg Parnell Lola and Trevor/Jim) – wins his second F1 race since clinching the championship only four months before; and Graham wins the Saloon Car race, too, again heading the Jaguar 3.8 battle featuring Roy Salvadori and Mike Salmon. Jack Sears wins his class in a Ford Cortina GT; Sir John Whitmore wins the Mini division; Roy Salvadori leads home Innes Ireland in the big sports car event (Cooper Monaco, Lotus 19); our friend Mike Beckwith wins his class with the 1600 Normand Lotus 23B; Pete Arundell and Paul Hawkins head the 1100 Lotus 23 class; and Denny Hulme, a new rising star from New Zealand, brilliantly wins a wet Formula Junior race in the new Brabham (from Frank Gardner, Pete Arundell and Mike Spence).

With no vested interest other than as a guy who loves motor racing, Bruce McLaren has this to say about Denny’s win: “For a driver who professes not to be particularly good in the wet, I thought fellow-New Zealander, Denny Hulme’s win in the works Brabham FJ was very good. For a couple of years he ran his own FJ Cooper as a privateer with very little outside assistance, and he did much better than anyone expected.  He is now being trained in the Brabham tradition by building, working on, and developing his own car. He works in the Brabham racing shop under Jack’s watchful eye and his fine drive in the rain at Aintree was the result – his first really big win for some time, and a most convincing one at that.” No surprise, really, that Bruce would sign Denny to his McLaren F1 team some five years later.

He is now being trained in the Brabham tradition by building, working on, and developing his own car. He works in the Brabham racing shop under Jack’s watchful eye and his fine drive in the rain at Aintree was the result – his first really big win for some time, and a most convincing one at that.” No surprise, really, that Bruce would sign Denny to his McLaren F1 team some five years later.

And, about Jim Clark’s performance at Aintree, Bruce is unequivocal: “It is interesting to note the way that Jim Clark is taking over the Moss role in motor racing. After practice at Aintree on the Friday, a certain well-known driver said to me, ‘I’m very pleased with my car – very pleased indeed. I’m only half a second slower than Clark’. There was a time when the proud phrase ‘only just slower than…’ just had to refer to Stirling Moss.”

Note: driver-swapping would continue through to 1964, when Jim took over Mike Spence’s Lotus 33 at the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen.

Images: LAT Photographic

Captions Top: Jim Clark dances with the throttle in Trevor Taylor’s carburettored 25. Middle: Jim in the early phase of the race in his own, fuel-injected 25. Bottom: Denny Hulme made his name by winning the wet Aintree FJ race