Jim Clark’s first race meeting of 1963 did not go particularly well. After several hectic weeks in the US (at Ford’s proving ground in Arizona and then at Indy, where he lapped at just over 150mph) and, before that, at Snetterton, testing the gorgeous Lotus 29 Indy prototype car,

Jim Clark’s first race meeting of 1963 did not go particularly well. After several hectic weeks in the US (at Ford’s proving ground in Arizona and then at Indy, where he lapped at just over 150mph) and, before that, at Snetterton, testing the gorgeous Lotus 29 Indy prototype car,  Jim drove back along the A11 to the Norfolk circuit for the Fourth Lombank Trophy F1 race. Probably at some point, I suspect, the new Honorary President of the Scottish Racing Drivers’ Club would have been smiling at the thought of the Club Lotus dinner he’d attended a few weeks before at the Taggs Island Casino, near Hampton Court. He, Jabby Crombac and Mike Beckwith had driven one of the new Elans onto the stage and the evening had ended with Colin Chapman being spruced up in a pair of blue nylon knickers… As would become the norm for races at Snett, Jim would be staying with Jack Sears in Jack’s farmhouse near the circuit – and he would refrain, of course, from making any long-distance calls to the US. (On Saturday, March 30, 1963, it became possible for the first time to make direct calls between the UK and the US.)

Jim drove back along the A11 to the Norfolk circuit for the Fourth Lombank Trophy F1 race. Probably at some point, I suspect, the new Honorary President of the Scottish Racing Drivers’ Club would have been smiling at the thought of the Club Lotus dinner he’d attended a few weeks before at the Taggs Island Casino, near Hampton Court. He, Jabby Crombac and Mike Beckwith had driven one of the new Elans onto the stage and the evening had ended with Colin Chapman being spruced up in a pair of blue nylon knickers… As would become the norm for races at Snett, Jim would be staying with Jack Sears in Jack’s farmhouse near the circuit – and he would refrain, of course, from making any long-distance calls to the US. (On Saturday, March 30, 1963, it became possible for the first time to make direct calls between the UK and the US.)

This would be the second Snetterton race meeting promoted by the circuit’s new owners – Motor Circuit Developments (the first was a club meeting held on March 17) – and therefore by John Webb, whose airline, Webbair, had become a regular part of motor racing logistics since the late 1950s. As a journalist, manager and, as I say, race promoter, Webb would in the 1960s and 1970s become one of the most influential figures in British motor sport. With support from Grovewood Securities, the Grovewood Awards, to name but one of Webb’s creative ideas, would eventually pave the way for today’s Autosport Awards.

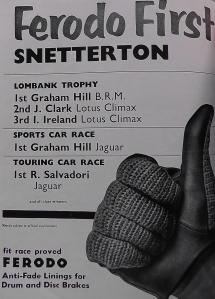

The Lombank Trophy was the first F1 race of the year – a non-championship race, to be sure, but a significant one nonetheless. Lombank was one of several London-based financial “institutions” (as investment banks were known then!) to see the benefits of motor racing sponsorship, although by a certain irony this Snetterton race would be the first since one of Lombank’s major competitors – UDT Laystall – announced their withdrawal from F1.

Today we go into internet-fed panic mode whenever teams or sponsors pull out of the sport, or change hands, but 50 years ago the usual ruptures of the winter were accepted with good grace in the belief that something – or someone – better would come along. One thing was clear, however: Stirling Moss’s retirement now seemed permanent (following a test at Goodwood in early May, Stirling would make the decision final) and he was busy now re-inventing himself as a team owner/team manager/Ogle Associate Director; and gone, too, were the factory Porsche and Lola F1 teams. Although General Motors also announced a unilateral withdrawal from motor sport in early March, 1963, one of the private entrants at Snetterton (Jim Hall) no doubt read this notice with a smile. (Even as Jim drove his BRP Lotus 24-Climax with not a little natural speed, the idea of a secret GM-supported Chaparral was formulating in his fertile mind. Jim had raced his be-finned and be-spoilered front-engined Chaparral at Sebring the weekend before; and many, he knew, were the ideas he could take to GM. Looking back now, and remembering for how long Jim was a fixture at F1 races, it is staggering that no-one in F1 took serious note of the winged Chaparrals of 1966-67. Even Jim Clark’s attempt to mount a rear spoiler on his Lotus 49 at Levin, in 1968, was immediately quashed by Colin Chapman.)

Porsche’s loss was Jack Brabham’s gain: Dan Gurney signed over the winter to drive a second factory Brabham in 1963, and John Surtees stepped from Lola to Ferrari. (I can’t help reflecting here that Jack Brabham “lent” Big John his personal Lotus 24 to race in the end-of-season, 1962, Mexican GP, for Bowmaker Lola were by then concentrating on the upcoming Australasian Series and entered only one Lola in Mexico for Roy Salvadori. John promptly qualified the 24 on the second row, only fractionally slower than Trevor’s Lotus 25. Brilliant. Surtees drove most of the New Zealand-Australia series for Bowmaker Lola but his place at Sandown Park, Melbourne, interestingly enough, was taken by Masten Gregory. Tony Maggs finished third at Sandown in the last appearance of a Bowmaker Lola entry.) ATS, led by former Ferrari engineer, Carlo Chiti, would also be entering F1 in 1963 with drivers Phil Hill, Giancarlo Baghetti and (for testing) Jack Fairman; and this would also be the first race for Coventry Climax since being bought by Jaguar Cars Ltd.

The Lombank Trophy race (won in 1962 by Jim Clark) was held on Saturday, March 30, at 3:00pm, with practice taking place on Friday. Public address commentary was in the care of the excellent Anthony Marsh, the recently-appointed Publicity Officer for Brands Hatch, Mallory Park and Snetterton and the lynchpin, of course, of the Springfield Charity that still exists today.

Jim and Team Lotus had only recently lost the 1962 World Championship to Graham Hill and BRM. No-one doubted that the monocoque Lotus 25 had been the quicker car in 1962 – but, since August, BRM’s Tony Rudd had been hard at work on his version of the Lotus “bathtub”. Quickly, though, work at Bourne fell behind schedule. The demands of the ’62 season in part accounted for the delay but in addition England was plagued by a ‘flu epidemic over the arctic-spec winter: factory staff were thin on the ground and there was little or no back-up to replace them. On top of that, BRM also began work on the radical Rover-BRM turbine programme for Le Mans. As a result, BRM began the year with lighter versions of their reliable and very driveable P578 space-frame cars, albeit with slightly more powerful V8 engines. They brought two to Snetterton, for Graham and for Richie Ginther, both of whom had been racing in the Sebring 12 Hours the weekend before. Hill finished third there, sharing a Ferrari 330LM with Pedro Rodriguez, and Ginther sixth (Ferrari GTO, shared with Innes Ireland). (These were the days of Boeing 707 intercontinental air travel, although turbo-props, such as the Lockheed Electra and Vickers Viscount, were still very much in use.)

Team Lotus entered two Lotus 25-Climaxes for Jim and his regular team-mate, Trevor Taylor but a shortage of engines (ie, one Climax V8 only!) rendered Trevor a non-starter. Jim’s race engine, indeed, was way down on power. Climax had planned to bring the new, 200bhp fuel-injected V8s to Snetterton for use by Lotus and Cooper but, like BRM, ran out of time. Speaking of the Cooper Car Company of Surbiton, Surrey, Bruce McLaren flew from Sydney to the US after winning his fourth Australasian series race at Sandown Park, Melbourne with his Intercontinental Cooper-Climax – (this is a sad story, but I’ll tell it less we forget: Bruce sold that car to Lex Davison, who raced it successfully in 1963-64 and who in turn then used it to enable the young and talented Rocky Tresise to make his career breakthrough in 1965. Tresise died in a start-line accident at Longford with the Cooper, as did the talented Australian photographer, Robin d’Abrera; it was Robin’s pin-sharp images that captured Bruce’s Sandown win in the Cooper for Autosport back in March, 1963) – and at Sebring raced the Briggs Cunningham Jaguar E-Type. He finishing eighth there, partnered with Walt Hansgen. Cooper entered only Bruce at Snetterton – again in a 1962 T60 car. The interesting Cooper entry from Morris Nunn failed to appear; and Jo Siffert pulled out after hitting a bank on the very wet practice day in his Filipinetti Lotus 24.

Jim, in battle-scarred, dark blue, peakless Everoak helmet,

was easily fastest on Saturday, lapping in 1min 44.4 in the torrential rain despite trouble starting the car (due to a lack of warm-up spark plugs). Eventually the 25 was tow-started into life. With Graham Hill’s BRM suffering from chronic fuel injection problems, Richie Ginther was next quickest (1min 46.8sec), followed by Bruce (1min 48.8sec), Innes Ireland in the BRP Lotus 24 and Innes’s team-mate, Jim Hall.

On Saturday the weather continued. Snetterton became a quagmire of mud, rain, wind and spinning wheels. There were no branded jackets back then, there was no North Face, no Timberland. Instead, long raincoats, cloth caps and Wellington boots ruled the day. Les Leston’s racing umbrellas – each segment representing a marshal’s flag – were also at a premium.

Richie led from the line, using the superior torque of the BRM engine to full advantage, with Bruce second and Jim an initial third. Jim quickly took second place at the hairpin – the left-hander at the end of the long back straight that runs parallel to the A11 – and passed Richie at the same place a few laps later. Significantly, though, Richie was able to out-accelerate the Lotus. All were running on the new Dunlop R6 but the traction advantage was with the BRMs. Graham Hill had meanwhile flown through from the back of the grid. He quickly passed Bruce and, now on a spray-free road, quickly caught Jim and Richie. Jim took the lead and began to pull away – but then ran wide onto the grass while lapping a back-marker; Richie again ran at the front.

There was no stopping Graham Hill. Driving superbly in the rain, he passed both Richie and then Jim to win decisively. Unhappy with his engine, and finding the 25 surprisingly skittish in the wet, Jim backed away and settled for second place. Innes Ireland eventually finished third, although not without incident. During his battle with Bruce, the pair of them had lapped Innes’ team-mate, Jim Hall. Innes slipped past without problem but then, with hand signals to Hall, made it clear that he wanted his team-mate to hold up Bruce for a corner or three. You can imagine if Fernando Alonso today suggested to Felipe Massa (running a lap behind) that he hold up Seb Vettel for 20 seconds or so. As it was, Bruce afterwards dismissed the episode as “a legitimate team tactic”. Such was Gentlemen Bruce.

The Lombank meeting boasted a superb support-race programme. The World Champion was also victorious in the 25-lap sports car race with John Coombs’ lightweight Jaguar E-Type (ahead of the Cooper Monaco of Roy Salvadori, now retired from F1); Roy made up for that by winning the Jaguar 3.8 battle in the 25-lap Touring Car race, gaining revenge on Graham Hill (who fought his way back from sixth place). Mike Salmon, also in a 3.8, finished third. Both Normand Racing Lotus 23s (driven by Mike Beckwith and Tony Hegbourne) had looked quick in the sports car event but eventually, in the wet, had to cede position to Alan Foster’s amazing MG Midget. It should be noted that Frank Gardner also raced the new Brabham BT8 sports car at Snetterton, winning the 1151cc-2000cc class.

I mention the Normand Lotus 23s because Jim signed over the winter to race for Normand whenever his schedule allowed. Just such an opening would appear at the BARC’s Oulton Park Spring Meeting on Saturday, April 6.

Full report next week.

Pictures: LAT Photographic and writer’s archive

The beautiful spring weather continued as Jim and Trevor made their way to Imola via Bologna. For both drivers, this race was a first. Imola – running through the vineyards and orchards of beautiful, undulating countryside – was in 1963 better-known as a motor-cycle track that had seen some sports car racing in the 1950s. There was no “Ferrari” element to it back then: the circuit had actually been developed by the Italian Olympic Committee, based on public roads.

The beautiful spring weather continued as Jim and Trevor made their way to Imola via Bologna. For both drivers, this race was a first. Imola – running through the vineyards and orchards of beautiful, undulating countryside – was in 1963 better-known as a motor-cycle track that had seen some sports car racing in the 1950s. There was no “Ferrari” element to it back then: the circuit had actually been developed by the Italian Olympic Committee, based on public roads.