From the gloss of Indy to the switchbacks of Mosport

Indianapolis was barely over when Jim Clark left for Mosport – for the next race on his crammed 1963 calendar

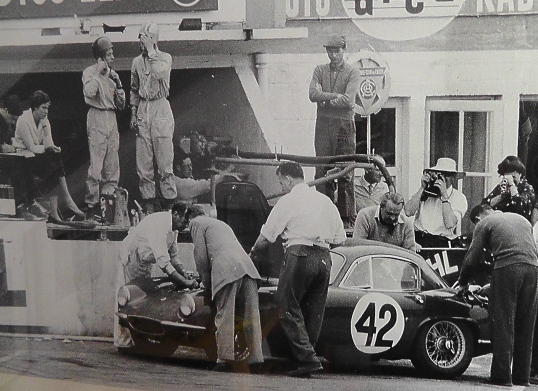

The young rookie, Skip Barber, in his ex-Ian Walker Lotus 23, leads Jim Clark’s similar, Al Pease-owned, Lotus 23 around Mosport Park

There were times when going to Mosport so soon after Indy did not seem like such a good idea. It was a rush from beginning to end – but then Jim Clark was used to rushing. It was what he did in order to earn his profession as a racing driver. Starting money, particularly in North America, was beginning to look very appealing – and Jim had always been open to the idea of driving different cars in different locations. In March, 1962 – long before Dan Gurney initiated the Indy plans – Jim had been delighted when Colin Chapman had asked him to race a Lotus Elite at Daytona; whilst there, he had had no hesitation in accepting an invitation from “Fireball” Roberts to try a stock car on the banked tri-oval. By 1963, with Indy elevating him to a new level of consciousness in the American racing psyche, Jim was open to all sorts of offers. The Player’s 200 was one such. The promoters would pay him decent starting money – and he could squeeze the race in between Indy and Crystal Palace back in England on Whitmonday. It also looked as though Team Lotus would be able to run the Milwaukee and Trenton USAC races later in the year. Then there were the big-money sports car races at Riverside and Laguna Seca at the end of the season. It all added up to an interesting, diverse and very busy year. Jet lag, of course, had yet to be invented!

In the meantime, there was no time either to savour his second place at Indy – or to be frustrated about it; and that was probably a good thing. He needed to be on that plane to Toronto. Parnelli Jones, by contrast, cancelled his upcoming appearance in the Player’s 200 with Frank Harrison’s Lotus 23B and flew instead to New York: he would be a guest on Johnny Carson’s Tonight show.

Jim had Dan Gurney for company on the flight to Canada but the trip felt less solid than usual. Jim was plunging into the unknown with a Comstock Lotus 23 – a deal put together via Lotus North America – and Dan with Timmy Mayer’s Cooper Monaco; his regular, and super-quick, Arciero Lotus 19 would instead by driven by Chuck Daigh. Both arrived tired and drained in Bowmanville, Ontario. There was just time for a couple of exploratory practice laps before the two-part race on Saturday. Dan was instantly fast – good enough to be fourth – but Jim was dismayed. The car wouldn’t run. He couldn’t even put a lap together.

With Comstock’s support, Al Pease, an excellent “preparer” of cars who was originally going to race his own Lotus 23, quickly stepped in to offer Jim his seat. Jim looked the car over – he knew 23s pretty well by then – and accepted straight away. He put in a lap that would enable him at least to qualify. It would, I think, also be the first time that Jim drove a car sponsored by a company from outside the motor racing sphere: Al had arranged backing from “Honest” Ed Mirvish, a Toronto-based discount store owner. Jim was amused by the concept; if he had time, he agreed that he would visit the shop before returning to the UK.

This was a big event by Canadian – even North American – racing standards. The driver line-up included Dan, of course, plus Jim Hall in the front-engined Chaparral, Lloyd Ruby, Daigh, a racer-mechanic who lived in Long Beach, Ca, Graham Hill (who had withdrawn from Indy and had flown to Canada from Monaco) in the rapid BRP Lotus 19, Jim’s friend, Sir John Whitmore, in the Frank Costin-re-bodied SMART (Stirling Moss Automobile Racing Team) Lotus Elan, and Roger Penske in Mecom’s Zerex Special (a car that Bruce McLaren would later use to kick-start his own team). Even so, the media at the time made very little of Jim Clark’s appearance. All the local talk was of drivers like Ruby, Gurney, Hall, Penske, Jerry Grant and Daigh – and of the reigning World Champion, Graham Hill. Jim, “only” second at Indy two days before, and in a much less competitive 1.5 litre Lotus 23, earned but a footnote in the local newspapers. After all the glitz and attention of Indy, Jim liked it that way. The weather was gorgeous in Canada; he worked for two days at Mosport with his little team in the little-car section of the paddock.

I think this also highlights another side of Clark’s professionalism: Jim wasn’t concerned with always racing cars that made him look good in the public eye; he wasn’t afraid to finish second – or lower than second – if that’s the way things went: his priority was always to give 100 per cent – and that meant driving with a team he could trust and in a car he liked. Lotus never built the strongest cars in the world – but that was another subject. Driving for Lotus – driving any Lotus – was about loyalty to Colin Chapman and about choosing a balance. What Lotus gave away in reliability they usually made up for with speed. Jim was prepared to accept that balance up to a certain level; and in Canada, in Al Pease’s Lotus 23, he found a level that at least represented par. When Jim was out there, driving the unfamiliar black car in this relatively minor race (by F1 World Championship standards), he was nonetheless driving absolutely on the limit. That was his code.

As it happened, Jim had a lot of fun in Canada. He quickly began to race in company with a young American who had made his way with an Austin Healey Sprite and then a Turner, and was now having his first race outside the USA in a yellow, ex-Ian Walker, Lotus 23. Skip Barber would go on to establish the biggest, and most successful, racing school in North America but on this Saturday, in late May, 1963, he was definitely a kid on a mission. “Mosport was a wonderful circuit,” he would say later. “Blind brows, changes of camber and barriers close to the circuit – where there were barriers. I trailored the 23 up from Connecticut, where I was based. I was so new to it that I didn’t even realize that they used imperial gallons in Canada. “I had bought one of the two Ian Walker 23s that raced in North American in 1962. It was used-up but successful – yellow with a green stripe down the middle. The Player’s 200 was a big event in North America – and in Canada, particularly, where they had major races in the spring and then in the fall. This eventually led to the Can-Am, of course. There was good prize money and starting money. And there was a big crowd at Mosport. The atmosphere was electric.

“Jim’s spec was identical to mine – a 23 powered by a 1500 Ford pushrod. We had no chance against the twin-cams, let alone the big-bangers. I’d only done two short races with the car before Mosport so this was definitely a step into the unknown. I don’t remember meeting Jim during practice or before the first heat, but between races I asked Al if he could lend me, or sell to me, a new set of brake pads. He replied that he would have to ask the driver (who happened to be standing right next to him!). Jim was extraordinarily gracious: he pretended to think about it for a second or two but clearly he was never going to say no. “This probably sounds a bit pretentious, but we had just had a tremendous, 100-mile race in which we had been separated by maybe three yards the whole time, with me in front.  He was very complimentary and very nice. I remember him saying ‘I’ll see you in Europe’…but of course I didn’t even know where ‘Europe’ was. Jim told a friend of mine later that he had thought about tapping me a few times during the race but my response was that he would have needed to have been a bit closer to have pulled that off. In the second heat he passed me but then I re-passed him on the same lap. We ran the same way almost until the end, when one of the RS61 Porsches blew up in front of me. I went so far off the race track that I couldn’t find my way back. I’m not kidding. I was in the tunnel exit of the infield, buried in heavy grass. After that, we just packed up and went home. And Jim flew back to Europe. It was as quick as that. I never even thought about asking Jim to help me meet people, or even to introduce me to people in the paddock. I never even considered it.”

He was very complimentary and very nice. I remember him saying ‘I’ll see you in Europe’…but of course I didn’t even know where ‘Europe’ was. Jim told a friend of mine later that he had thought about tapping me a few times during the race but my response was that he would have needed to have been a bit closer to have pulled that off. In the second heat he passed me but then I re-passed him on the same lap. We ran the same way almost until the end, when one of the RS61 Porsches blew up in front of me. I went so far off the race track that I couldn’t find my way back. I’m not kidding. I was in the tunnel exit of the infield, buried in heavy grass. After that, we just packed up and went home. And Jim flew back to Europe. It was as quick as that. I never even thought about asking Jim to help me meet people, or even to introduce me to people in the paddock. I never even considered it.”

Jim’s race was similar in essence to one he would enjoy a couple of years later at Lakeside, in February, 1965. Like Barber, Australia’s Frank Matich would race that day wheel-to-wheel with Jim Clark – Jim in the works Lotus 32B-Climax, Frank in the powder blue Team Total Brabham-Climax. Like Barber, Frank would forsake an international career for a racing life at home. Both drivers earned Jim’s respect.

The 1963 Player’s 200 was won by Chuck Daigh; Graham Hill retired with a blown engine. Jim Hall was second, Dan third, Penske fourth. Jim eventually finished eighth overall (and third in class). John Whitmore amazed the crowd (and Barber, who had never seen an inside wheel so far from the ground) before the differential seized on the SMART Elan. John then drove with Jim back to Toronto and flew with him to London and thus on to the Mayfair flat. The two of them were scheduled to race at Crystal Palace on Whitmonday, 24 hours later.

Captions, from top: Skip Barber in his ex-Ian Walker Lotus 23 leads Jim Clark in the Al Pease “Honest Ed’s” Lotus 23. Jim is wearing his new Bell magnum, complete with white peak; Honest Ed’s discount store in Toronto (as it was in 1963); the sponsor’s signwriting was relatively large by ’63 standards; Skip and Jim as they spent much of the Player’s 200 Photographs: Skip Barber Collection; Peter Windsor Collection